When they discovered her body, she was surrounded by a pool of dried blood. Diane Fossey She had been dead for a few days in her hut in the middle of the Virunga Mountains Rwanda. Everything showed that this death was particularly violent His skull and face split in half almost symmetrical machete clean.

The murder occurred on December 26th. 1985exactly forty years ago and still It is not entirely clear who is responsible for this. First, there was a supposed scapegoat. And there was also, as it emerged over the years, a conspiracy that may have involved the highest authorities of this Central African country.

Fossey was one of the most important zoologists of the 20th century. But it was a long road before it became this global reference. He was born in San Francisco, USA, in 1932 and devoted his early adulthood to working as an occupational therapist. He specialized in the rehabilitation of children suffering from polio.

But in 1963 a trip changed his life. He took out a loan to study Africa and there his path crossed with that of the archaeologist Louis Leakeya dedicated student of Primates. The researcher was convinced that the more he knew about these animals, the more he would know about the development of the human species.

Fossey became increasingly interested in Leakey’s work and the archaeologist “recruited” her to his team of primatologists who became known in the scientific field as “Trimates”. One of them was none other than Jane Goodall, Birute Galdikas and Fossey.

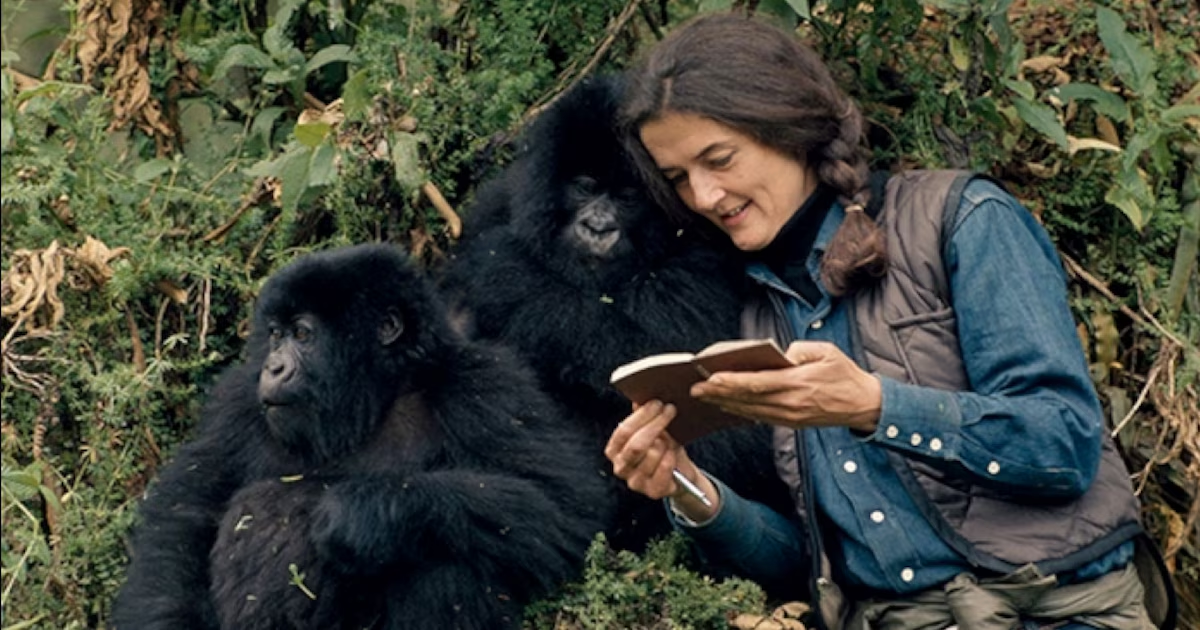

Fossey decided to take an unprecedented approach to the gorillas that lived in the mountains of Rwanda. She settled there in 1967, devoting herself entirely to her work as a primatologist and determined to become more and more like the creatures she studied so that they could be included in her daily life.

The former occupational therapist founded Karisoke, the research center she built in the middle of the mountains where the area’s gorillas lived, under constant threat from them poaching. Fossey implemented this extreme mimesis: He walked on his knuckles, chewed wild celery, and even kicked guttural sounds so that the animals he studied would accept them in his backpack.

The opportunity to get so close to these animals helped her prove, through the discoveries she was able to make over the years, that they were a rather friendly species and that aggressiveness was far from being their main characteristic.

On January 1, 1978, Dian Fossey’s life changed forever. Digit, his pet gorilla, was killed by poachers. They shot him in the chest, cut off his head and mutilated his hands to sell them as ashtrays. Fossey became deeply depressed and developed problems with alcohol consumption.

At the same time, the primatologist decided to move into a phase that she called “active conservation,” which involved the use of… Violence against those who threatened gorillas of the mountain she protected. Dian increasingly abandoned scientific research to become a physical guardian of primates in the mountains of Rwanda.

He resorted to extreme methods. He patrolled the area, destroying the traps set by hunters one by one: he destroyed more than a thousand in just a few months. In addition, he burned down the huts of locals who he believed were suspected of attacking the gorillas, and he even said so in the book he wrote about his experiences in Rwanda had kidnapped a hunter’s son and physically tortured another to drive them out of the jungle. Fossey even attacked tourists and guides, arguing that the area should be left as untouched as possible.

Exactly forty years ago, an as yet unidentified murderer ended the primate researcher’s life. It was an assistant at his research center who found the body, lying face down between two beds and bathed in blood.

The murderers had entered through a hole in one of the side walls of the hut. With a Pangaa machete, usually used by poachers in the area, split the victim’s skull and face in two. Paradoxically, there was one in Fossey’s room Panga On one of the walls hung: It was a kind of “spoils of war” that he had taken from a hunter a few years ago.

After the crime scene was discovered, it was determined that Dian had attempted to defend himself with a weapon. But in her desperate attempt to load it as quickly as possible, she chose the wrong ammunition and was completely helpless.

The possibility that the attack had occurred in the midst of a robbery was almost immediately ruled out. There were broken glass and scattered furniture at the scene of the accident, but absolutely nothing was missing. The researcher’s cash, traveler’s checks and very expensive photographic equipment were intact. That was immediately clear The intent had been murderand the revenge hypothesis was examined.

The Rwandan judiciary quickly pointed this out to the investigator Wayne McGuire as a possible murderer. He was a young researcher who worked with the victim, and the judiciary of the Central African country assured that McGuire killed her out of “professional jealousy” because she had failed to complete her doctoral thesis.

However, the American researcher fled to his home country before Rwanda sentenced him to death in absentia. This would become apparent some time later it had been a “scapegoat”. to hide the real murderers.

Over time it became more and more important. Hypothesis that she was killed by poacherssome of whom viewed her as her greatest enemy. The Hunters also wanted revenge for any retaliation Fossey took after Digit’s murder.

As the case gained global prominence, evidence mounted that the Rwandan government itself was at least complicit in the murder, regardless of who the material perpetrator was.

The fact is that in addition to her strong opposition to the hunt, the guardian of the mountain gorillas has been vocal against tourist exploitation from this area of the country. This had a direct impact on the country’s revenue as it was one of the biggest attractions Rwanda could offer its visitors.

Fossey’s death managed to “pave the way” for the country to develop tourist activities, which today, paradoxically, represent an essential income for the conservation of the species it preserves.

Dian Fossey’s body was buried in the gorilla cemetery she created. The chosen location was a synthesis of his life: he rests right next to Digit, the gorilla he wanted to avenge through cruel methods.

The last thing he wrote in the diary in which he recorded his life and work was: “When one realizes the value of life, one becomes less concerned about arguing about the past and more focused on protecting the future.”

The text was an almost perfect summary of his decades of work. The thing is: As a conservationist and guardian of mountain gorillas Fossey had managed to expand these Rwandan territories from around 250 individuals of this species to almost a thousand.. His goal was achieved, but he had lost his life in the process.