Between life and death in a hospital bed after being stabbed during the 2018 electoral campaign in Juiz de Fora (MG), Jair Bolsonaro begins to recapitulate his life. Ultimately, he survives and is elected president of Brazil.

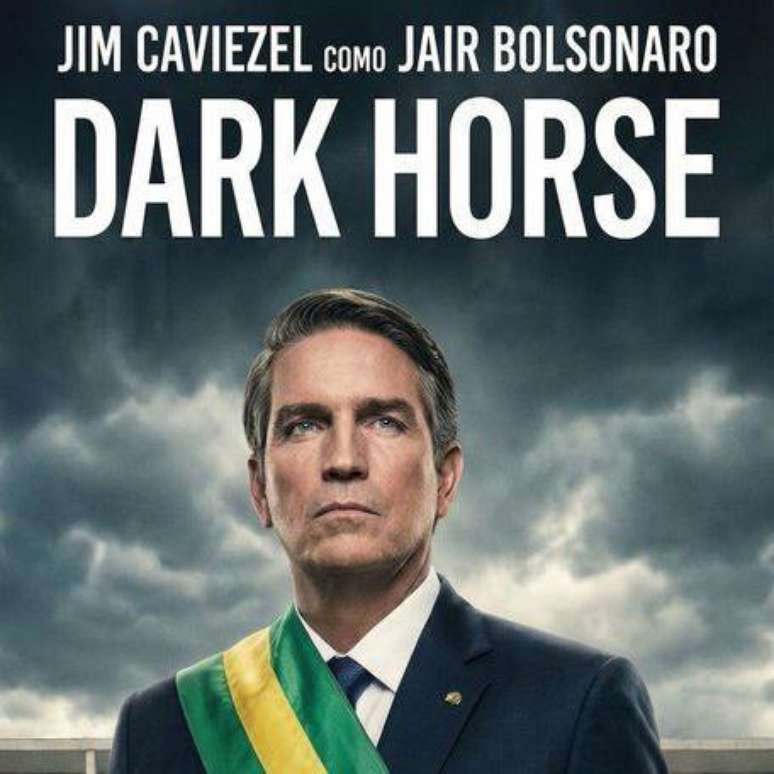

This is the plot of the film Black horse (something like Azarão, in free translation), the first images of which have been distributed on social networks in recent weeks by Bolsonarista politicians and supporters of the former president.

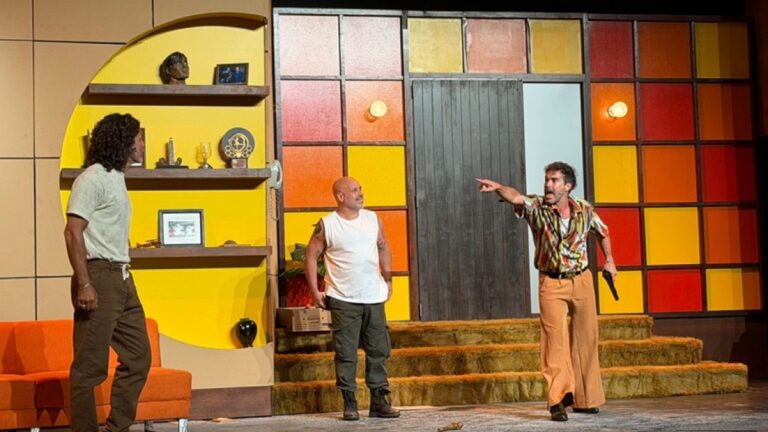

The recordings finished in December, in São Paulo, and the film entered the editing phase in the United States.

The film’s release date has not yet been announced — a thriller “Very low budget” by American standards, according to federal deputy Mário Frias (PL-SP), former Secretary of Culture in the Bolsonaro government and main creator of the production. He also plays a doctor.

The idea, according to the film’s director, Cyrus Nowrasteh, in an interview with BBC News Brasil, is that the release will take place in 2026, the year of the presidential elections.

But, in addition to pleasing the Bolsonaro base with a fictionalized story and “poetic license” about its greatest leader, now imprisoned for attempted coup d’état, the film is part of a global ecosystem of productions with themes dear to right-wing and conservative leaders.

Frias himself said that the idea of production came from the teachings of Olavo de Carvalho, ideologue of the Brazilian conservative new right. The guru, who died in 2022 in the United States in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, argued that there was a hegemony of the “communist” left in culture and that conservatives must take control of these means of influence.

“I had seen a video in which Olavo de Carvalho spoke about the culture war and I found it fantastic because I didn’t see it in the mouths of people who represented the right. I saw a lot of people on the right on the issue of security and the economy,” Frias said in an interview with the right-wing channel Conversa Timeline.

Researcher on this so-called cultural war, sociologist Marco Dias explains that, for new global rights, the prevailing defense is that there is a current culture “in crisis”.

This idea, says Dias, is spreading even if, in the human sciences, it has already been “deconstructed, because there is no single culture, this idea of Culture with a capital C”.

“But the right-wing bloc positions itself as a cultural warrior, wanting to transform this culture or, in a reactionary way, return to a time in history when they thought things were simpler,” says Dias, a professor at the Federal University of Sergipe (UFS).

As this is considered a “war” for conservatives, there is a search for allies for the battle.

According to Frias, the idea to make the film came in 2022, after a heart attack and depression. It would be a way of thanking the former president for the role he played in his life.

The MP said he sought financiers for the project among names he had encountered on the American right when he was a member of the Bolsonaro government – names he said he could not reveal for contractual reasons.

Director Cyrus Nowrasteh says he was developing another project to make in Brazil when an American producer put him in touch with the production company GoUp Entertainment, owned by Karina Ferreira da Gama and Mário Frias.

Marco Dias believes that Black horse this precisely reflects the search of the right in Brazil to integrate into the movements of the global conservative right, notably in the United States.

“There is a very strong dialogue with these trends of Christian cinema of which the director and the main actor themselves are part,” he says.

Writer and director Nowrasteh is an Iranian-born American filmmaker with a history of producing productions with strong Christian and political appeal.

His most famous film is The stoning of Soraya M, which deals with extremism in the true story of a woman sentenced to death in a public square in Iran for a false accusation of adultery.

The film received some recognition by taking third place in the Audience Award at the Toronto International Film Festival, Canada.

Nowrasteh’s filmography revolves around films more focused on Christianity, “good versus evil”, little recognized by critics.

In an interview with BBC News Brasil, Nowrasteh said he “felt like there were a lot of unanswered questions” regarding Bolsonaro’s assassination.

“This will help illuminate a lot of what is happening today in Brazil – and around the world,” he said.

The role of Bolsonaro in Dark Horse is an old acquaintance of Nowrasteh from his films and, according to Frias, was his only choice: American actor Jim Caviezel.

He gained international fame in 2004 when he played Jesus in the film The Passion of Christby Mel Gibson, marked by controversy in the United States for its violence and the accusation of allegedly promoting anti-Semitism by focusing on Jews as guilty of the death of the Messiah.

After this production, Caviezel’s career focused on films with religious themes or arguments dear to the right.

His most notable production of recent years is The sound of freedomwhich saw the mobilization of evangelicals and Bolsonaristas to become box office leader in Brazil and in the world in 2023.

Recorded in 2018 and financed by independent investors, the film tells the story of a US government agent (in real life, Tim Ballard; and, on screen, Jim Caviezel) who dismantles a child sex abuse ring operating in Colombia.

Ballard is the head of the nonprofit Operation Underground Railroad, which investigates cases of child victims of international sex trafficking and is widely revered by the American right, including President Donald Tump.

Ballard was later accused of using his power within the organization to commit sexual abuse, according to reports seen by The New York Times.

The sound of freedom He has also been associated by critics with the US QAnon movement – which propagates the theory that politicians like Trump are waging a secret war against pedophile child traffickers and Satan worshipers who allegedly hold high-ranking positions in the US government, business and the country’s press.

Caviezel himself attended a QAnon-themed conference in 2021 and appeared several times on the podcast of ideologue Steve Bannon, who went so far as to say that the QAnon theory is “a good thing.”

At the time, the film’s producer denied that the film harbored conspiratorial ideas.

Caviezel is a practicing Catholic and, at events, has spoken about the importance of faith to his work and the existence of a “decadent” culture.

Openly a supporter of Trump, he agreed to play Bolsonaro without negotiating values, according to Mario Frias.

In a video shared on social media by Frias’ wife, Juliana, it is possible to see Cavizel praying in Aramaic, a language said to be spoken by Jesus Christ, with Carlos Bolsonaro on the film set.

“Jim would be the only one who would agree to play a controversial role like this,” Frias told Conversa Timeline.

“If things were fair, it was Oscar’s thing.”

The sound of freedom It had an impressive box office as an independent film and, according to analysts, was evidence of a suppressed demand for religious cultural productions aligned with the values of both groups who identify as conservatives and those aligned with the American radical right.

Added to this phenomenon is the rise of religious-themed productions which were niche and are now accessible to a large audience on streaming platforms, that is to say broadcast in real time on the Internet.

For sociologist Marco Dias, who follows right-wing cultural production, the cinema frontier was the last to be crossed by this sector which believes in the need to occupy cultural spaces.

“It’s about growing step by step,” he says.

“These are very well structured networks, in which we already have a series of publishers who translate right-wing books, and platforms like Brasil Paralelo”

Dias believes that cinema still has few notable examples, because film production is the most difficult to achieve and the most expensive.

Therefore, says the expert, the film about Bolsonaro with international participation will inevitably be considered “a great victory” by the Brazilian right, making the story of the former president accessible to the whole world.

“It’s a project that will probably have visibility, with the construction of Bolsonaro as someone who is persecuted – and maybe he will have a very big market within these groups of the new global right.”

The producer has already received parliamentary amendments

The production of the Dark Horse film is entrusted to the company Go Up Entertainment, owned by Karina Ferreira da Gama.

The producer appears in public documents as responsible for renting the Memorial da América Latina, a cultural space in São Paulo, for the recordings. The value was R$126,000.

Gama is also president of the National Academy of Culture (ANC), a company which has already received, via parliamentary amendments from PL deputies, 2.6 million reais to produce a series on “national heroes”.

The businesswoman is also a partner in the Instituto conhecimento Brasil, which last year received more than 100 million reais from the city of São Paulo to provide Wi-Fi internet to low-income communities in the city, according to a report by Intercept Brasil.

This institute also received in 2025 two amendments worth one million reais each from MP Mário Frias, creator of the film about Bolsonaro. The projects funded by Frias were aimed at encouraging sports and another on digital literacy.

Frias did not reveal the origin of the resources for the production of Black horse and said he would never do it with “public funds” or with the support of laws like Rouanet.

In interviews he mentions that he received great support from SPCine, the city of São Paulo and the government of Tarcísio de Freiras.

The São Paulo government and São Paulo City Hall told the BBC that they had not provided any support for the production.

“The SPCine authorized the recording of the said film after technical analysis, following exactly the same procedure used in all requests received by the Municipality,” specified the town hall.

BBC News Brasil attempted to contact Mario Frias and Karina da Gama, but received no response.