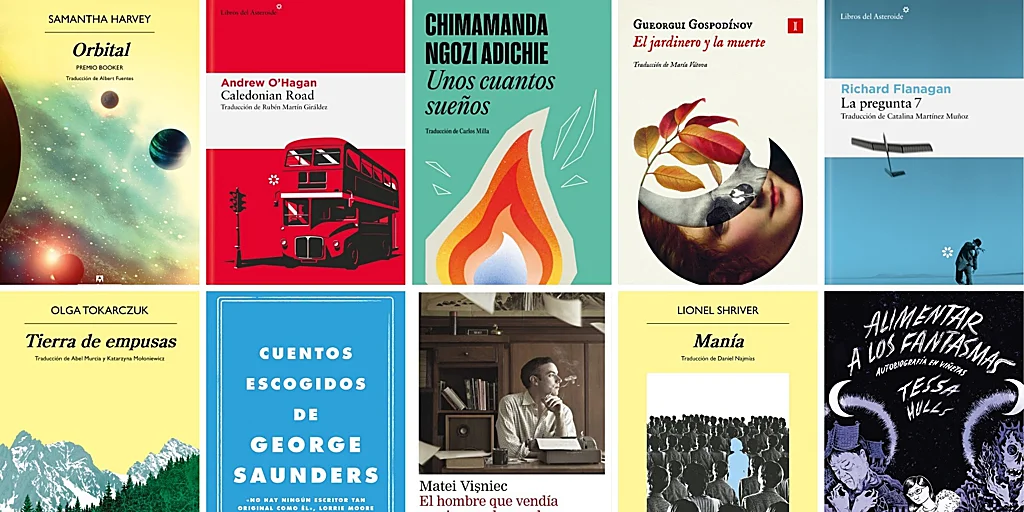

The year began with “Orbital” (Anagrama), a novel in which Samantha Harvey locks us in the International Space Station with six astronauts: nothing happens inside, only life, a woman who looks out the window, thinks and immerses herself in … its transcendences, in a state of permanent weightlessness: “Perhaps human civilization can be compared to the life of an individual. As we grow up, we abandon the royalty of childhood to achieve supreme normality; We discover that there is nothing special about us and, in a surge of innocence, we are overcome with absolute joy: if we are not special, perhaps we are not alone. This is perhaps the great novel of confinement.

Andrew O’Hagan

Caledonian route

In “Caledonian Road” (Asteroid Books), Andrew O’Hagan immerses us in the London of 2021, but in the middle of a 19th century novel, very Dickensian, his reference. “It was time to make a contemporary novel that explores the different social and economic layers. It was ambition. “It took ten years of work,” he told us while passing through Madrid. It has been sold as the great novel of post-Brexit England, but it is rather the story of people who have money, people who are afraid of losing it and people who wish they had it.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

some dreams

Another novel written as a fresco from another time is “A Few Dreams” (Random House), Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie’s return to fiction after a decade. The writer tells the life of four women linked by family, friendly or professional ties, and tells us about love or motherhood or social dramas with a humor and lightness well above the criticism devoted to them.

Georgiy Gospodinov

The gardener and death

Of course, self-literature has not disappeared in 2025. Georgi Gospodinov gave us in “The Gardener and Death” (Impedimenta) the poetic account of the death of his father. It is a book whose beginning is already the history of literature: “My father was a gardener. “Now it’s a garden.”

Richard Flanagan

Question 7

Richard Flanagan (Asteroid Books) has also written about his father. In “Question 7”, the Tasmanian mixes his stories with those of the world, and ends up linking his existence to the atomic bomb of Hiroshima: it is thanks to this bomb that his father was saved from the Japanese concentration camp of Ohama. It also wouldn’t exist without Rebeca West kissing a writer 114 years ago in a London living room: his name was HG Wells. It’s a fascinating book.

Olga Tokarczuk

land of empusas

In “Tierra de empusas”, Olga Tokarczuk (Anagrama) resurrected tuberculosis as a tone and theme. “Sanatorium culture is fascinating in itself: sanatoriums created an alternate reality that gave rise to particular human relationships and a specific culture of people condemned to illness and, ultimately, death,” he tells us during the novel, which is something of a paraphrase of “The Magic Mountain.” “The absence of women in the novel seems dark and hostile to me.”

George Saunders

Selected stories

The “Selected Stories” (Seix Barral), by George Saunders, are a perfect sample of one of the great contemporary storytellers of the English language: a writer who conceives of history as a laboratory, a playground or a party that one arrives at by chance because one has seen an open door. Or a dream. Or delirium.

Mateï Visniec

The man who sold the beginnings of a novel

“The man who sold the beginnings of the novel” (Galaxia Gutenberg), by Matei Visniec, we meet a man who belongs to a secret lineage dedicated to providing first sentences to writers stuck in their beginnings: Kafka, Wells, Canetti, Melville, Camus…

Lionel Shriver

Mania

It’s a hilarious game that rewrites recent history, just like “Manía” (Anagrama), where Lionel Shriver offers us an alternative version of the world since 2011: intelligence is frowned upon, Obama loses the elections because he is talkative, Benedict Cumberbatch is unemployed because everyone hates “Sherlock”… In short, we’re laughing.

Tessa Cases

Feed the ghosts

The year ended with “Feeding the Ghosts” (Reservoir Books), by Tessa Hulls, the second comic book in history to win the Pulitzer for memoir and autobiography: the other was “Maus,” by Art Spiegelman. It is a ghost story, that is, of guilt and reconciliation. In the background, the Chinese dictatorship, repression, foreigners, uprooting… And even the West.