Sonia, Ana, Teresa, José Miguel, Genoveva, Antonio or Carmen are the names behind the data that shows that the primary care situation in Almería is overwhelmed. Like more than 36,000 citizens who live in the suburbs of the capital Almeria, they suffer daily from the lack of resources that causes a bottleneck in the Andalusian Health Service (SAS), which affects outpatient clinics and leaves residents without effective care. Something that the Andalusian government itself recognizes, with nuances.

Tired of the situation, a group of them, led by Antonio Galdeano, collected more than 3,000 signatures and appeared before the Health Delegation of Almería so that the inappropriate scenes and situations of the year 2025 stop happening in primary care. Clinics that have not opened for months due to infrastructure problems, people with reduced mobility who have to travel very far from their home or the problem common to the rest of Andalusia: the delay in the simple consultation of the family doctor who waits more than a week in most cases.

Sonia tried it last week. The app informed him that someone would call him “within 72 hours.” The call came, yes, but to tell him to come at seven in the morning and wait in line because there were only four appointments available for that day. “And then the waiting rooms are empty. But completely empty. Nobody understands it,” he laments. A situation that repeats itself again and again: make an appointment, wait between 10 and 14 days and, if things get complicated, end up in the emergency room. All this while the Ministry of Health had promised that appointments would be given in less than 72 hours.

Healthcare Chaos

But the reality, as Marea Blanca Almería reports, is very different: “Appointments are never found in less than 7 to 10 days,” they emphasize, with examples of delays reaching 14 to 20 days in several centers in the capital. In the neighborhoods and villages surrounding Almería, the situation is getting even worse. Only one doctor arrives in San José in the morning and the minimum time to get an appointment is one week. In El Pozo de los Frailes, two consultation days per week mean two weeks of delay.

And in towns like El Barranquete, Albaricoques, Los Escullos or La Isleta del Moro, the doctor only comes once every seven days. If someone finds themselves in an emergency situation outside of established hours, they will have to wait for an ambulance to arrive from El Toyo or Níjar. In an aging population, this is not just a management problem: it is a health risk, according to neighborhood residents.

José Miguel, one of the residents affected by the lack of resources, sums up the situation: “We are small towns, of course, but we are also people. And here, health care has been left without a place.” In Albaricoques, the office closed more than six months ago after the demolition of the previous building. No alternatives are enabled. The only first means they have is a telephone number which is not always answered in time.

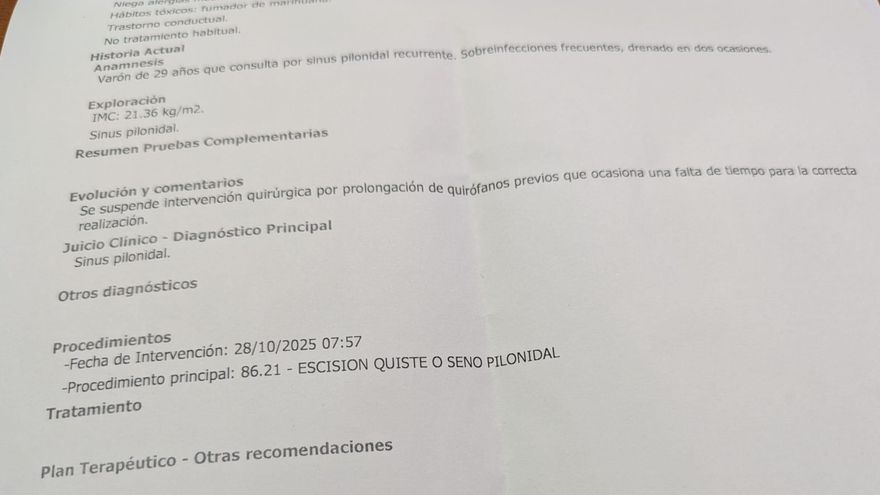

While all of this is happening, hospitals are experiencing their own collapse. A 29-year-old young man with an infected pilonidal sinus that had been drained twice required surgery. However, it was suspended because there was no time in the operating room due to the delay accumulated in the previous interventions: “The surgical intervention is suspended due to the prolongation of the previous operating rooms which causes a lack of time for its correct execution”, we read in the medical report to which this media had access. One more case which illustrates that the traffic jam begins in health centers and ends in hospitals.

Neighborhood exhaustion

Antonio Galdeano explains that the neighborhood platform that is being implemented against the Junta de Andalucía was born because “it has become continuous and permanent”. Lack of sick leave coverage, constant rotation of locum doctors or exceeding quotas. Cabo de Gata has around 1,900 cards per doctor, Retamar reaches 2,000, well above the legal recommendation of 1,200. Result: a family doctor who is no longer “the usual doctor”, the one who knows your history, but rather a professional who is different each time and, too often, distant and unknown.

The Almería health district, however, rejects that the root of the problem lies in the lack of personnel. They assure that staff have been “covered and reinforced in recent years” and that the delays respond to a “new model of care” which reduces consultations per doctor – from 60 to 35 per day – for “more personalized and quality” care. They also announce future office expansions and space divisions in La Cañada, Retamar and Cabo de Gata, with the promise of going “hand in hand with neighbors and professionals” to achieve “close, equitable and quality” care.

But the neighbors insist: since July they have been asking for a meeting with the Health Delegation. The request was reiterated in September. “Total silence,” denounces Antonio. And while they wait for that response that doesn’t come, they continue to add signatures, continue to raise their voices, and continue to remind people that public health should not depend on getting up early to wait in line, living near an office that remains open, or being lucky enough to have a doctor that day.

Because for Sonia, Ana, Teresa, José Miguel, Genoveva and so many other people, there is nothing more fundamental than knowing that if one day they wake up in pain, their health center will be there. And who will answer.