The mummification artificially developed by the people Chinchorro on the coast of the Atacama Desert, considered the oldest known in the world, has been reinterpreted by experts as an artistic manifestation with profound therapeutic and social implications. According to an article published in Cambridge Archaeological JournalNew hypotheses suggest that the origin and development of this practice, dating between seven thousand and 3,500 years before the present, was associated with high infant mortality and linked art, ritual and the search for emotional relief, although with unnoticed health consequences due to exposure to toxic pigments.

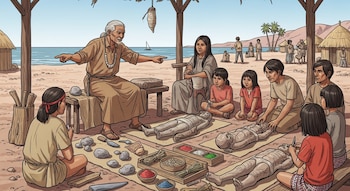

Research led by Bernardo Arriaza claim that the Chinchorro mummification techniques originally emerged as a mechanism to channel the grief caused by the high infant mortality rate, which in many cases was linked to the arsenic poisoning present in the Chinchorro waters Valleys in northern Chile. He The study shows that transforming bodies into visual and aesthetic icons allowed families to process loss and maintain bonds with the deceased. “The transformed body became a canvas for the expression of emotions and a place where these ancient people could have found emotional healing and comfort,” Arriaza said.

This approach transcends the traditional vision of the Chinchorro as fishermen and gatherers and offers new perspectives on their social structure and the importance of funerary art as a tool of cohesion and resilience. Mummification functioned as a symbolic process of coping with grief, involving both individuals and the community.

The Chinchorro communities were established in areas where water toxicity far exceeds safe limits and arsenic concentrations are up to hundreds of times higher than the recommended limit. This environment promoted frequent spontaneous abortions and an infant mortality rate of nearly 26%, similar to other hunter-gatherer groups, according to research data. Arriaza warns that infant deaths in small populations could threaten family survival, reinforcing the need for rituals that provide meaning and continuity to those who are absent.

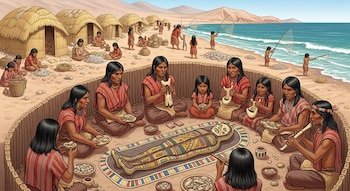

Resilience to these tragedies was reflected in increasingly sophisticated burial rites, with detailed treatment of corpses and their preservation within the community, as well as ceremonies to strengthen social bonds and ancestral memory. The funerary art of Chinchorro represents a collective response that combines grief, creativity and the affirmation of identity.

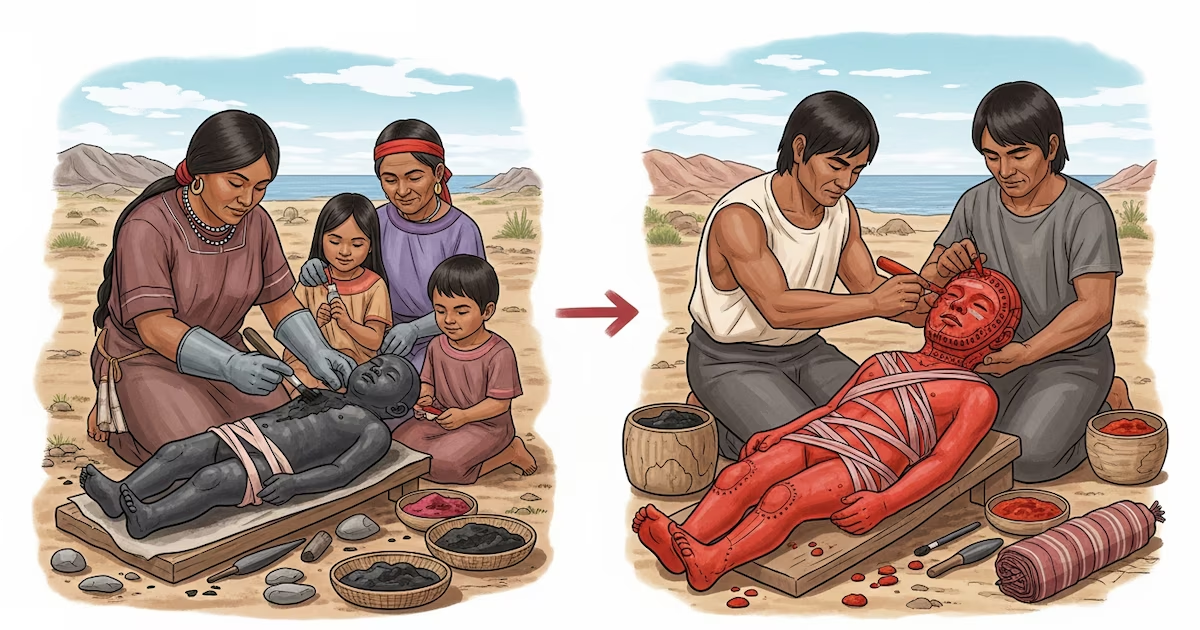

Making the Chinchorro mummies required a complex process: removing organs, filling them with fibers, clay and earth, assembling them with sticks, and reconstructing anatomical features through modeling and pigmentation. The use of pigments was particularly important: during the “Black Mummy” phase, manganese oxide was used to coat the body with an even shade of black; Later, in the “red mummies” stage, red ocher was used to cover the body and highlight the facial features and hair with other materials.

The colors not only fulfilled an aesthetic function, but also conveyed ideological and spiritual meanings: black stood for death and transition, red symbolized life and transformation, and white was associated with purity and change of state. These elements, together with the use of textiles and materials of animal and plant origin, formed true sculptures that reflect the skill and artistic sensitivity of the ancient inhabitants of the Atacama.

The production of the mummies required resources, community organization, and intergenerational transmission of techniques, underscoring their importance both to their collective dimension and to the final result.

Despite its artistic and symbolic depth, the continued use of manganese oxide has had detrimental effects on public health. The sources cited indicate that bioarchaeological analyzes have found high levels of manganese in the tissues of mummified individuals, with no clear difference between men and women, suggesting widespread and prolonged exposure.

The study documents this About 21% of the bodies examined have toxic levels of manganese – over 10 ppm – with Parkinson-like neurological symptoms: motor changes, hallucinations, pathological laughter and loss of facial expression. The gradual identification of this damage could have favored the progressive abandonment of black pigments and thus favored the switch to red ocher and the adaptation of techniques to less harmful forms.

Research also suggests that the making of mummies changed gender roles. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that during the “black phase,” women led the burial processes, particularly of infants, while men took a central role during the “red phase,” reflecting social changes and community dynamics.

Over time, factors such as the recognition of toxic risks, the emergence of new economic activities, and demographic changes contributed to the decline of more complex forms of mummification. However, the legacy of the Chinchorro culture remains regional identity of northern Chilethrough art, collective memory and debates about heritage and health.

The Chinchorro funerary heritage marks the origin of the funerary art known in the Americas integrate the boundaries between art, therapy and ritualand leave lasting traces that continue to expand the interpretation of the Andean past.