Until the ballot boxes were banned – Chilean law prohibits their disclosure in the 15 days before the election – average support for the presidential candidate of the left-wing bloc plus the Christian Democratic Party, communist activist Janet Jara (Santiago, 51), was 28%. This figure is similar to the almost incombustible approval rating of President Gabriel Buric, which usually fluctuates between 28% and 30% (at the worst it was 22% and at the best it was 35%). But it is still far from the 38% support that the left gave, in the September 2022 referendum, for the – failed – proposal to draw up a new constitution that was promoted by this sector.

According to the Pulso Ciudadano poll, conducted by Activa Research and presented a month before Sunday’s elections, 78.3% of Chileans who support Jara approve of Boric’s government. 62.6% of his followers sympathize with the center left, while 22.7% define themselves as “without a political position.”

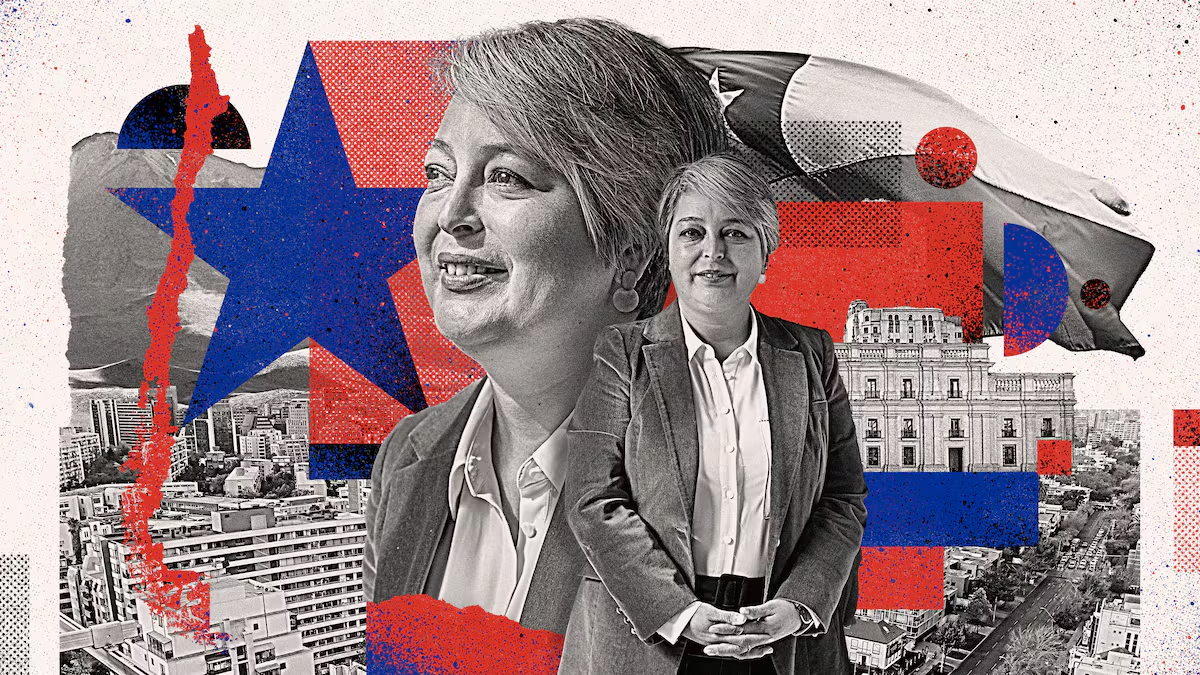

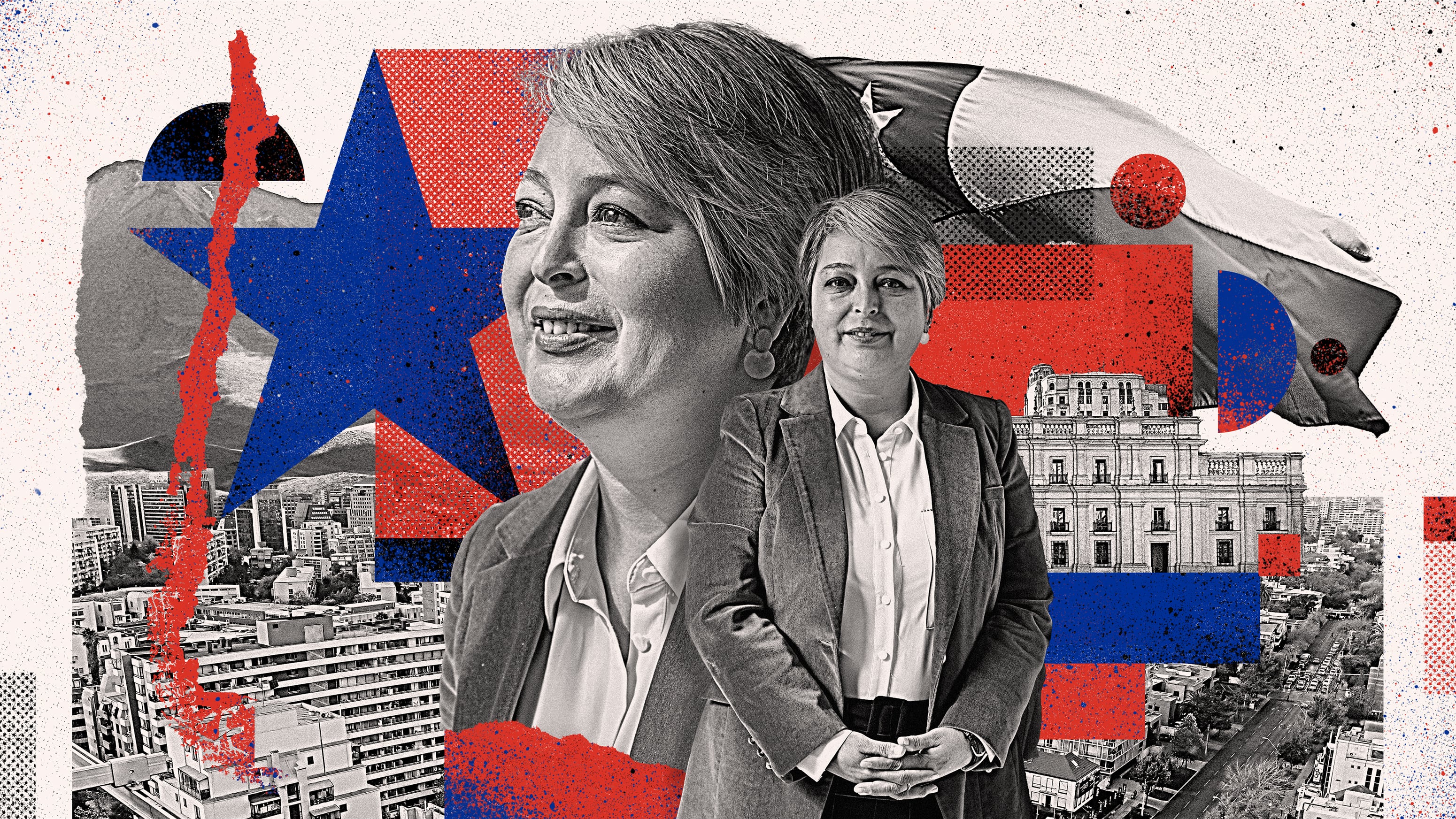

The 51-year-old general manager, lawyer and master of public administration is in first place in the polls. But she will almost certainly go to the second round, most likely with Republican Jose Antonio Cast, a far-right conservative. Part of the Ultras’ campaign is to negatively impact its relations with Buric, since she was Labor Minister in his government. “Jara is Buric and Buric is Jara. Nothing she says or does can change that. She is the successor to a failed government,” he said on Tuesday afternoon to his supporters at the end of his election campaign at the Movistar Arena. Jara was doing the same activity, but in Maipo Square: “Chile is not collapsing; it is a great country,” he assured his supporters.

Jara led Buric’s labor portfolio between March 2022 and April 2025: he resigned to begin his path to La Moneda. In that ministry, he led the initiatives he presents today in his campaign that benefit the most vulnerable Chileans. Among them are a historic increase in the minimum wage to 500,000 Chilean pesos (just over $500) and pension reform. He also implemented a law that reduced the working day to 40 hours per week.

Today, Jara speaks specifically to a large portion of these Chileans: he proposes public health reform, the expansion of universal day care, and the right to adequate housing. His program and speech focus on those who wake up at six o’clock every day and go to work by bus, he repeatedly says. “We will ensure that every Chilean family can make ends meet in peace. This is my commitment, this is my seal. Dignity, decent work and good wages, and that is why we will work to strengthen the living wage,” he said Tuesday in Maipo.

A week ago, the candidate said on social media that she asked her followers if they remembered her first salary. “Many of the responses were the same. The money is not enough and it is difficult to make ends meet.” Then he repeated his election promise: that the workers’ vital income would reach 750,000 pesos (about $795).

In this story, his personal story was central and defined the identity of these voters: he grew up in the town of El Cortijo, in the municipality of Conchali, north of Santiago. She lived with her parents, a housewife, a car mechanic, and her four siblings for periods of poverty. Even from relatives in a relative’s home. “I never imagined that I would become a candidate for the presidency of the republic,” she recalled at the conclusion of her campaign on Tuesday. “Not because I thought I could not do it, but because it is unusual for someone who comes from El Cortijo to open the doors of the seat of government.”

But she also, like all candidates, makes security, economic growth and controlling illegal immigration among her priorities. “We don’t want hate, we don’t want discrimination, and we don’t want families’ legitimate fear of being assaulted to be used as a campaign tool,” he said. He added: “In my government there will be greater security in the neighborhoods” as well as a “preventive approach.” He also proposes lifting bank secrecy so that the prosecutor’s office follows the path of organized crime funds.

The candidate faces a major challenge: searching for new support that will help her win over the right-wing candidate with whom she will go to the runoff on December 14. But the context is complex: the latest poll by the Center for General Studies showed that 24% of Chileans today sympathize with the right, the highest level in history; 36% with the center and 20% with the left.

These elections also have many characteristics that make the scenario ambiguous, especially for the left. For example, it is the first presidential election to be conducted with compulsory voting and automatic registration, which means that about five million new voters,

It is also the first time since the return to democracy, in 1990, that the left faces three competing right-wingers: two radical, the libertarian Kast and Johannes Kaiser’s right, and one traditionalist, with Evelyn Matthey. But there is another uniqueness. Although Jara has the support of nine parties, his communist struggle, a Marxist-Leninist society that believes in the dictatorship of the proletariat, has caused a political dilemma among part of the moderate center left. A large section supports this, but there are others who do not dare to take this step. This, despite the fact that his platform supports the sector’s values, such as a “just society” and its support for individual freedoms: he said that if he reached La Moneda, he would support the abortion project without the issues promoted by Boric’s government.

Until Jara, the Communist Party had not succeeded in achieving a competitive presidential option in 35 years. But oddly enough, it was the computer that made the most of it Noise He made his candidacy uncomfortable at various times during the campaign. This fact was also part of the political dilemma facing some Chileans, including Buric’s former finance minister, Mario Marcel. Although he would give her his vote — “because I know her as a person and because I had to work with her” — he told this newspaper he would do so “with one apprehension: the role of the presidential council in his eventual government.” Another voice that reflects the situation is that of Ernesto Otton, doctor of political science, centre-left essayist, and chief advisor to Socialist President Ricardo Lagos (2000-2006): “You cannot be a communist and a democrat.”

But it was Jara, who transcends his ideology, who delivered the biggest surprise at the end of June, when he widely won the ruling party’s primaries and won by 60% over the social democratic candidate Carolina Tuha. Today it is supported by the Toha sector.

The candidate insisted that she represents a broad bloc, and she did so He gave signals to win over centrist and non-ideological voters, which is what he will need, above all, in an eventual runoff. She announced that she would leave her struggle if elected.