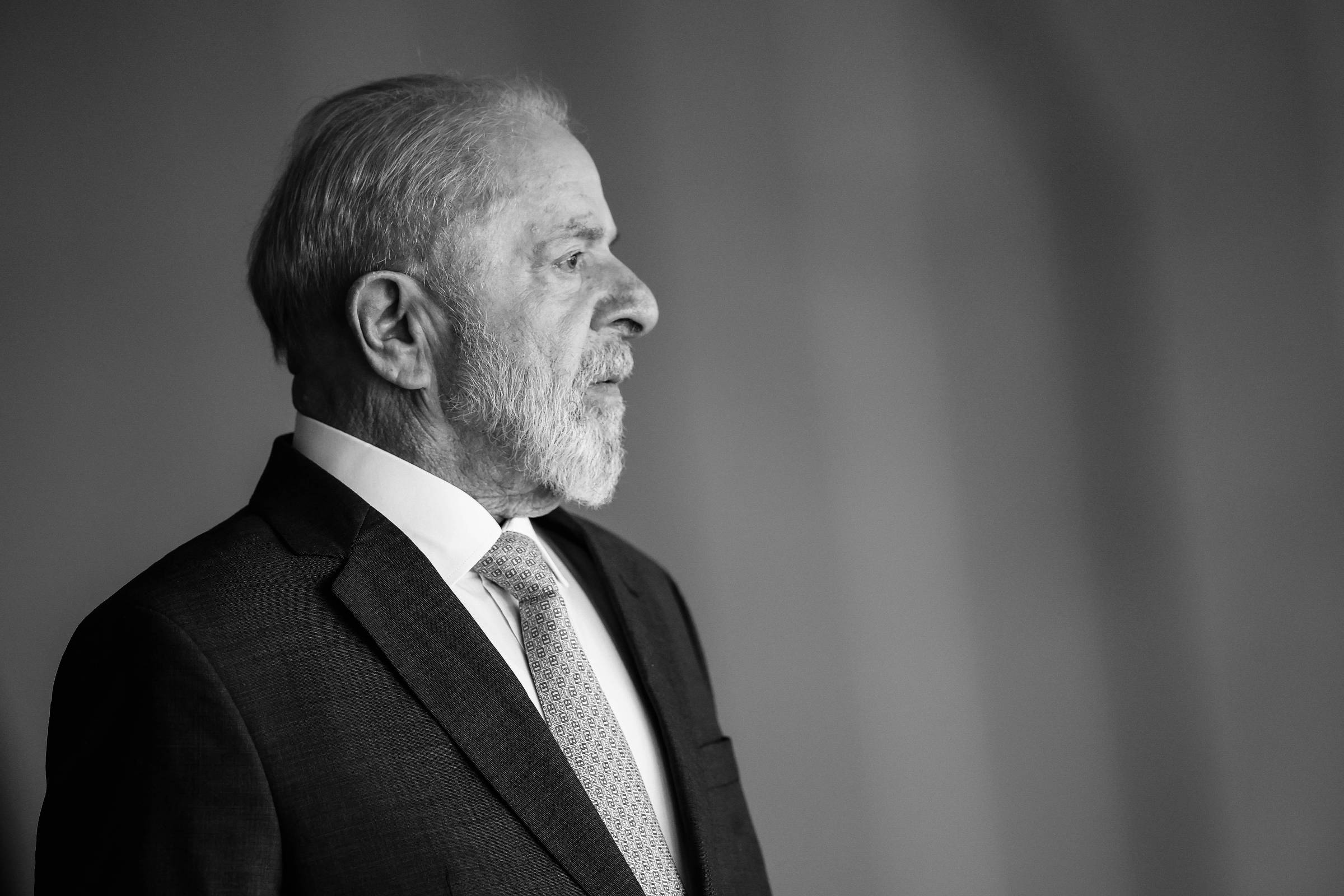

The restoration of the image of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (PT) seems to have reached its peak. Public opinion’s reactions to the police operation that led to the killing of 121 people in Rio de Janeiro served as the impetus for reabsorbing the political framework.

Recent research by Quest has connected the dots – on the one hand the security crisis and, on the other, the borderline stagnation of presidential popularity that divides voters nearly in half between those who support federal administration and those who disapprove.

It is possible to risk reaching this plateau anyway, despite the police operation in Rio’s favelas, or even as a result of another event with national repercussions.

The general framework that defined the very narrow outcome of the 2022 elections shows no signs of being relaxed. A clear majority of 50.9% of those who voted for Lula in the second round still support him as president. Those who reject it correspond roughly mathematically to the 49.1% who voted for Jair Bolsonaro (PL).

A segment of independent voters — sometimes swinging to one side, sometimes to the other — has swung back and forth in approval of the Labor MP since his inauguration in January 2023. The swing of the pendulum predicts that this segment in the middle of the ideological spectrum will decide presidential succession in October 2026.

This is good news for those who aspire to moderate political discourses and practices in Brazil. Journeys to extremes tend to be punished at the ballot box. The radical Bolsonarianism, whose leader has been stripped due to judicial convictions, is on track to exercise diminishing influence.

The president’s leftist moves – such as appointing Guilherme Boulos (PSOL) to the ministry – will have an electoral cost. A higher dose of spending will imply a greater risk of rampant inflation and a smaller margin for interest rates to fall. Politically apolitical voters vote against the incumbent president when they are dissatisfied with the economy.

Given the size of the National Congress, with its gradual dominance of budget implementation and the party oligarchs’ control of huge public campaign funds, the weight of the outcome of the parliamentary elections in the balance of ability to govern is increasing. The prognosis is bad for the left at this stage.

If Lula confirms his secret favoritism now, he may live in an environment more hostile towards Planalto than the current one in Brasilia. Add to this the possibility that an aging president, with no possibility of being re-elected, will have to deal with the consequences of the massive debt he has encouraged.

The best solution for Lula is not to wait until 2027 to correct the direction of politics and the economy. The signs are converging toward moderation. It would be tantamount to doing so now, even in the name of a Labor government remaining.

Editorials@grupofolha.com.br