The university is, par excellence, a space for discussion. In this environment, hypotheses confront, consensus is questioned, and disparate ideas compete for evidence-based space. However, this pluralism has been replaced by the forceful logic of consensus. Research projects that align with mainstream agendas increase their chances of being funded, professors modify the content of their disciplines to avoid friction, and in many cases, the simple act of espousing a discordant opinion is enough to relegate someone to the status of “problematic.” The result is clear: instead of intellectual diversity, an environment of conformity and expected silence is created.

- Tariff: Trump says he sees no room for further tariff cuts, but ‘distortion’ continues for Brazil

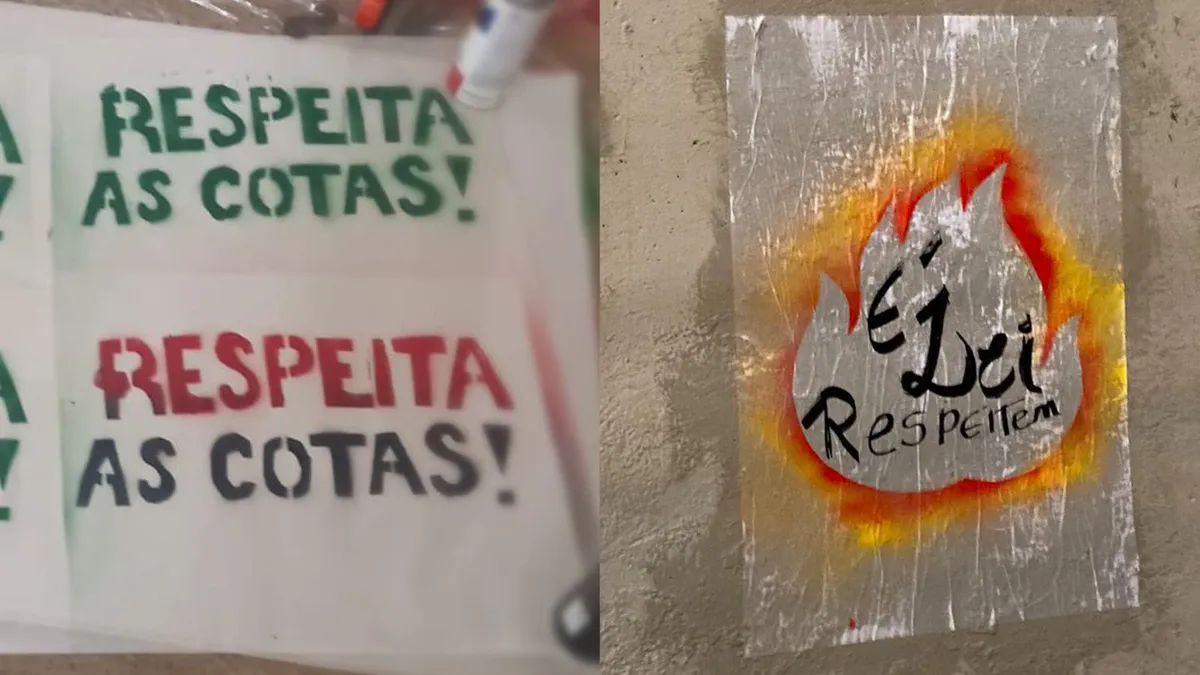

Academic freedom of expression research, conducted by the CEVIS Institute, helps assess this scenario. Nearly half of Brazilian students say they avoid discussing topics considered controversial in the classroom. The data suggest that even before arriving at the research field, the university already experiences a form of daily self-censorship. When students avoid certain subjects and teachers perceive the risk of criticism or institutional retaliation, many choose not to expose themselves. The ripple effect is devastating to the integrity of scientific research. Ideas that might generate fruitful discussions and conceptual progress are abandoned even before they take shape, for fear of the social cost of introducing them.

- See ranking: The CBF survey shows the largest number of fans in Brazilian football

The recent study conducted by More in Common showed that the group of “radical progressives” is the most educated, the richest and the whitest among the politically engaged in Brazil. The coincidence with the national intellectual elite, even if we cannot extrapolate the data, seems plausible to us. At the same time, we see a move from programmatic political polarization, in which we disagreed over state projects, to affective polarization, in which disagreement is seen as a threat to identity, as Felipe Nunes and Thomas Truman wrote in “Biografia do abysmo.” It is not surprising that the group is the furthest from the societal norm, as the research results confirm.

Whoever risks challenging the prevailing consensus in the university, where ideas are the focus of disagreement, is not just a theoretical opponent, but quickly turns into a moral enemy. The result is subtle but effective forms of exclusion: fewer invitations to newsstands, difficulties in joining research networks, “innocent” jokes and comments, and isolation in professional and social spaces. This movement erodes not only academic life but also the social function of the university itself. How can we create critical citizens if the institution proves unable to tolerate contradictions? How can we encourage innovation if funding standards favor research that “plays it safe,” while avoiding challenging accepted assumptions? The university, which should offer society knowledge and alternative solutions, is limited to reproducing learned common sense.

However, freedom of expression is not absolute, there are necessary moral and legal limits, as long as they are restricted and defined. The problem is when the boundaries between morality and ideological circularity dissolve, and every uncomfortable debate begins to be seen as a threat. At this point, what should prevent abuse ultimately limits debate.

It is necessary to ask: If the university is unable to support distancing, who will? Pluralism is neither a luxury nor a privilege; it is the minimum condition for science to remain a science. Without them, only single-minded clubs will remain – comfortable for those who are allied, but at the cost of imposing intellectual and social ostracism on those who dare to diverge, threatening the ability to produce innovative scientific knowledge.

*Fernanda Trompczynski is a researcher at the Sevis Institute, and Bruno Bolognesi is a professor at the Department of Political Sciences and coordinator of the Postgraduate Course in Political Sciences at the Federal University of Paraná.