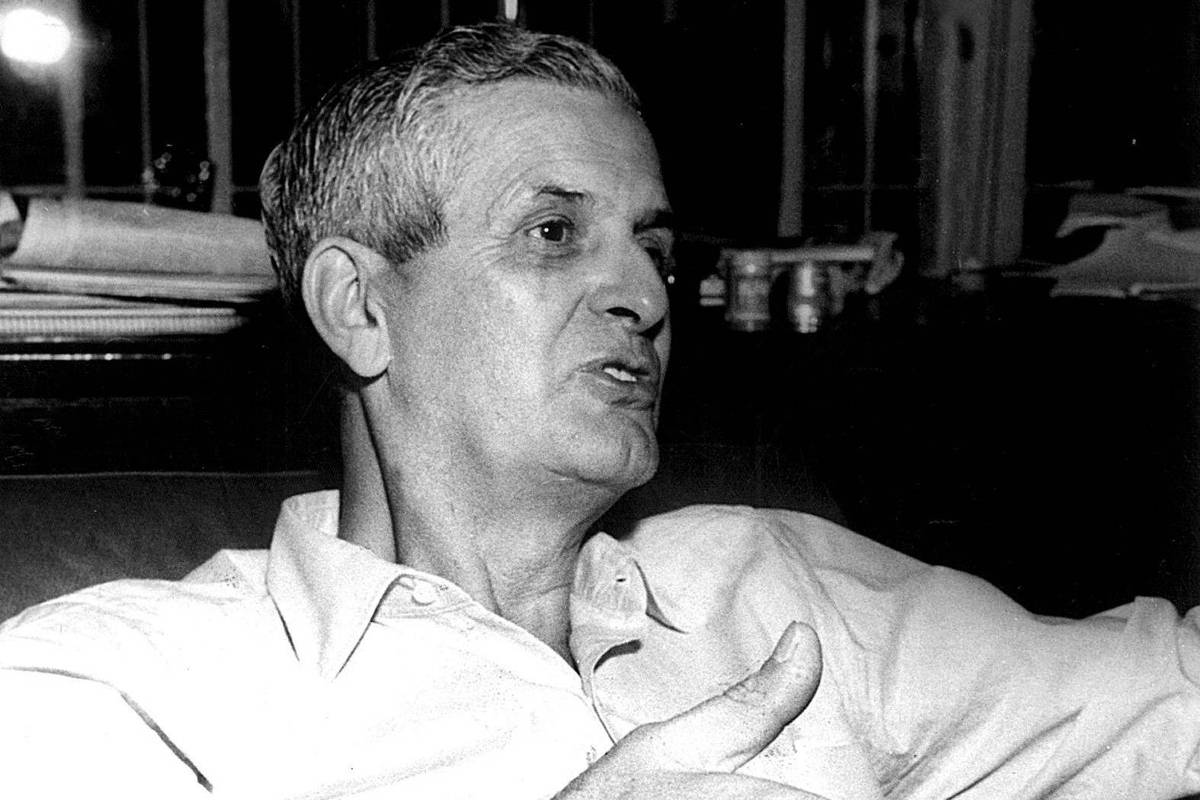

One of Brazil’s greatest thinkers, historian and geographer Caio Prado Jr. was thinking about democracy while watching European countries succumb to World War II.

“What fundamentally distinguishes democracy from fascism, and the vast majority of Englishmen, Americans and Russians who are fighting, are fully aware of it, is that in democracy not only does the state guarantee individual rights, but their defense and care are in the hands of the parties themselves, that is, the people,” he wrote in an article published in Folha da Manhá, in 1943.

In the early 1960s, the newspaper merged with Folha da Manhá and Folha da Tard to create Folha de S. Paulo.

Read the full text below, part of Section 105 Columns of Great Influence, which recalls the records that made history in Bound. This initiative comes within the framework of the celebrations of the 105th anniversary of the founding of the newspaper in February 2026.

Democracy and Fascism (05/13/1943)

When most of the world is engaged in a conflict like the present one, which is unprecedented in history, and when the issue under discussion, as we hear from everywhere, is democracy, it seems to me that there is nothing more important than trying to define this “democracy” in which the blood and tears of almost all of humanity flow.

What is dangerous about this matter is that there is not always agreement on this matter. But this is mainly due to those who seek to discuss the “concept” of democracy and its theoretical essence. Now, when the lives of millions are exposed at every moment to the defense of an ideal, it seems only fair to set aside these abstract discussions, and try to discover what it actually represents to those who struggle for it. In other words, what is the common denominator that currently unites the English, the Americans and the Russians, who are most committed to the campaign?

It can only be a certain form of political life to which they are accustomed and do not want to give up, and which is opposed to that represented by fascist weapons. What does this life consist of? It is not difficult, from the countless demonstrations, in the press, on the radio and many other things, which reach us from those countries of struggle, to judge the matter.

First, they defend respect for human personality against notions that place race, power, or other considerations above it; In concrete terms, this means respecting certain rights that all people consider essential for their existence and well-being. But this does not exhaust the topic, because German, Italian or Japanese fascism also recognizes, preserves and guarantees some of these rights.

What fundamentally distinguishes democracy from fascism, and the great majority of the English, American, and Russian people who are fighting, are fully aware of it, is that in a democracy not only does the state guarantee individual rights, but that their defense and protection are in the hands of the parties themselves, the people.

Through the various systems of political organization, which differ from one democratic country to another, this defense and guarding is exercised through the intervention of citizens in the formation and functioning of the state, by which they are permanently guided and supervised.

Not only through the election of representatives who serve as representatives in parliaments or other assemblies, but through the various ways available to them to express themselves freely: the press, rallies, popular organizations, marches, etc. Consequently, the interests and rights of the people, though handed over to the State, remain, through the direct and continuous control exercised over them, effectively under popular guardianship.

This is not a theory. This is what is practiced in virtually all major democracies today fighting fascism. Because this is precisely the denial of the people’s right to control and supervise the state’s agencies and actions.

The distinctive feature of the German, Italian, or Japanese system is the distinction between two distinct entities: the government and the people; He divided the population into two classes: one commanded and directed; Another of those who simply obey. Fascists base this distinction on the argument that public affairs are too complex for the people to solve; that he is “incompetent”, even in looking after his own interests and protecting his rights, and must therefore be entrusted entirely to the hands of his most capable rulers.

Under this pretext, true representative bodies and any free expression of thought are suppressed. Everything has been handed over to strict government control, and citizens must meekly bow down and wait for any concession or concern for their interests to come from above.

The fascist argument about popular incompetence involves sophistry. As such, in general, it confuses two distinct things: politics and administration; In other words, the general direction and supervision of public affairs with the effective performance of government services. In the latter case, people taken collectively are clearly incompetent; All citizens are not and cannot be simultaneously understood in legislation, justice, finance, public and economic education, etc.

But they are fully capable not only of supervising the implementation of these various services, which they control well based on the results, but also, above all, of establishing guidelines for general policy. Take a specific case: if it is a question of protecting the national industry against foreign competition in the domestic market, for example, only a specialist will be able to properly organize the tariff for this purpose. But as an expert on the subject, he would not be able to say whether the industry deserves protection.

It is a measure that benefits some and harms others. Through it, industrialists will ensure the sale of their products, and workers will find more work; But consumers lose, who will pay higher prices? Producers of exportable goods lose. Who should be helped? There are no technical and economic criteria to solve the problem radically. This is a political question, that is, it depends on an assessment of the greater or lesser number of interests at stake, on both sides. Such an assessment is not an issue that can be resolved with precise scientific and technical data.

It is up to the parties themselves, which in this case would be the entire population, the people as a whole, to discuss the issue and reach an agreement that harmonizes the differences. It will do this through the various means available to it in a democratic country: assemblies under its direct control, the press, popular organizations, etc. In one way, through the free expression of his thoughts. In this way it will be possible to resolve the matter with a minimum of grievances and errors; This is how this problem is effectively solved in democracies. If it were handed over to a group of individuals, however capable and honest, but closed behind four walls and vested with discretionary powers, there would be every possibility, if not certainty, that the solution would favor some at the expense of others.

Who can always guarantee that ability and honesty? That is why, in countries that are truly peacefully developing, superficial or ill-intentioned observers see disturbances where in reality there is nothing more than a discussion, albeit heated, but fruitful and life-giving. While the fascist states, under the appearance of peace that looks more like stagnation, discontent, complaining, ill-feeling, gossip and rumour, replace, but without the same results, because they are sterile, the honest and frank appearance of free thought.

The freedom to express one’s opinion, reject the heavy guardianship of dictatorial governments, and the ability to defend their rights and interests on their own, is what the democratic peoples of the world are struggling with today. All the English, Americans, Russians and their allies know this very well.