credit, Tel Aviv University

-

- author, Isabel Caro

- scroll, BBC World News

A revolutionary discovery for understanding the evolution of our species and modern human rituals.

This is how a group of scientists, in a study published last July by the scientific journal L’Anthropologie, defined the skull of a child who lived 140,000 years ago, which was found nearly a century ago in one of the caves on Mount Carmel in northwest Israel. The site is considered the oldest known cemetery.

The child was three to five years old. They may have been deliberately buried in that region of the Levant, the biogeographic corridor where gene flows of indigenous lineages and other groups from Africa and Eurasia mixed during the Middle Pleistocene.

The skull was named Skhūl 1° because it was the first fossil found by British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod (1892-1968) and American physical anthropologist Theodore McCown (1908-1969), who explored the area in 1931.

According to this new research, its appearance would be the oldest known evidence of miscegenation among humans Neanderthal and Homo sapiens.

It is well documented that the two species intermingled, and that we modern humans have between 1% and 5% of the Neanderthal genetic heritage. But the time in which Skhūl 1° lived makes a big difference.

“What we are saying now, in fact, is revolutionary,” explains Israeli paleontologist Israel Hershkowitz, a professor at the Department of Anatomy and Anthropology at Tel Aviv University in Israel, who led the research, to BBC News Mundo (the Spanish service of the BBC).

“We have proven that the first encounter between Neanderthals and… Homo sapiens “It did not happen about 50,000 years ago, as previously thought, but at least about 100,000 years ago, that is, 140,000 years ago, which is very important.”

But not all scientists agree with this conclusion.

Unclassifiable mosaic

Skhul I died at an early age of natural causes.

Not much is known about how he lived. It is also not possible to determine with certainty what disease could have killed him at such a young age, nor his biological sex.

It is known that he was buried alongside other children and adults in what is considered a mass grave, and it is one of the most important discoveries in paleoanthropology in the Levant region, at the beginning of the twentieth century.

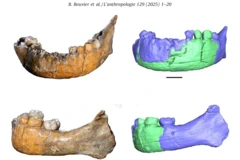

The shape of its skull and jaw (which had been mistakenly separated from the skeleton during excavation and embedded in plaster) has been re-evaluated in a new study, using CT images and virtual 3D reconstructions, to clarify its relatedness and classification.

When compared to the remains of other children, Homo sapiens And Neanderthals, the group of scientists led by Hershkowitz noted a “mosaic nature of their morphological characteristics” and a “morphological dichotomy” between the two parts.

In other words, while the overall structure of the child’s skull had typical features Homo sapiensJaw characteristics indicated a “strong affinity” with the Neanderthal evolutionary group.

credit, Dan David Center for Human Evolution, Tel Aviv University

“The combination of features observed at Skhūl 1° may indicate that the child was a hybrid” between a Neanderthal and a Neanderthal. Homo sapiensStudy details.

So far, the child has been classified as a modern human, but researchers point out that it is “almost impossible” to classify it into one group or the other.

Hershkowitz explains that the term “hybrid” does not indicate that he was the son of a Neanderthal and a Neanderthal. Homo sapiensRather, it is the result of the gradual mixing of races between the two species.

“We call it an introgression population, which means that genes from one population slowly and gradually penetrated the other.”

“So, in fact, what we observe in Skhul is a population of approx The wise one“But with a higher percentage of Neanderthal genes.”

In this sense, the researchers propose to classify the child as belonging to a “palodemos”, that is, a population characterized by great biological diversity, as a result of miscegenation, which deserves to be recognized as a specific group within the species.

credit, Dan David Center for Human Evolution, Tel Aviv University

Background of the boy of Lapidu and Yunxian II

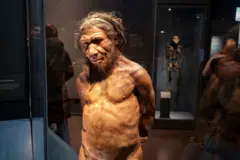

Until the late 1990s, there was scientific consensus that Neanderthals and modern humans could not have interbred, because they were different species.

For this reason, the almost intact skeleton of a boy from Lapedo, Portugal, was discovered in 1998, which also has mixed characteristics. The wise one And Neanderthals radically changed our knowledge of evolution.

The boy, who was about four years old, lived about 29,000 years ago. It showed clear hybridization between the two groups.

The revolution underscored by this theory came in 2010, when the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced. When compared with humans from different regions of the world, it was concluded that 1% to 5% of the DNA of non-African populations came from Neanderthals.

If the boy from Lapido showed us a recent crossroads in the history of human evolution, then Skhöl 1° marks a much earlier time.

In September, the journal Science published a study on Yunxian 2°, a million-year-old human skull found in China. It indicates, according to scientists, that Homo sapiens They began to appear at least half a million years earlier than we thought.

But researchers who studied Skhūl 1° say this finding has nothing to do with the conclusions of their study.

“It has nothing to do with development, nor with the interaction between… Homo sapiens The researchers say: “Neanderthals in the eastern Mediterranean.”

“The Chinese skull is supposedly very old and definitely does not belong to… Homo sapiensNor Neanderthals. It is not surprising that there are other types of Homo “Walking on Earth during the Middle and Upper Pleistocene.”

credit, Fudan University

“A little sense of biology”

Researcher Professor Antonio Rosas, from the Department of Paleobiology at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Spain, casts doubt on some of the findings related to Skhūl 1°.

For the academic, the fact that researchers rely on the typical cranial base coupling of Homo sapiens A jaw consistent with Neanderthal anatomy is a “hodgepodge” that, according to him, “doesn’t make any biological sense.”

“The genetic determination of anatomy is complex and is not usually tightly distributed in isolated bony elements, such as the skull and mandible,” he explains.

Furthermore, there is another, more recent example, which has also been suggested as a hybrid between Homo sapiens A Neanderthal – Lagar Velho, in Portugal – shows an unmistakably human jaw. Homo sapiensUnlike Skhul 1°.

For Rosas, the key lies in the classification and interpretation of the burial process, which, as we know, underwent changes after the burial itself.

“1° probability that the Skhul jaw is a Neanderthal jaw that ended up in a Neanderthal grave.” Homo sapiens This must be taken into account,” he highlights.

It is widely recognized in the scientific world that one of the great challenges of studying evolution is the ability to recover DNA from ancient fossils.

“There’s definitely a systemic problem here,” Rosas continues. “Hybridization between human species has not been conclusively reported by ancient genetic data.”

“Using morphological data alone, it is currently difficult to confirm these phenomena. We largely do not know how genetic information from Neanderthals and Neanderthals combined.” Homo sapiens It is expressed in anatomy.”

Other scientists have expressed similar concerns in various scientific journals. They are requesting DNA analysis of Skhūl 1° to verify the conclusions of this new study.

credit, Mike Kemp/Photos via Getty Images

Collaboration and funerary practices

In addition to drawing attention to supposed early hybridization in modern human evolution, Skhūl 1° also provides valuable information about two other elements: cooperation between the two groups and new perspectives on cultural practices historically associated with modern humans.

“The most dramatic and most important thing is that we now know that the two groups managed to live side by side for a very long period of time,” Hershkowitz highlights.

For him, this discovery continues to contradict the paradigm Homo sapiens It will be a species that imposes itself on others by the “law of the strongest.”

“This is the real surprise, because anthropologists have thought this for a long time Homo sapiens They were the only ones responsible for eliminating all other groups Homo On the ground,” Hershkowitz highlights.

“They did not disappear because we were aggressive species that drove them out, displaced them, or pressured them to extinction. On the contrary.”

“Basically, what happened is we combined these small groups into larger groups Homo sapiens Little by little they disappeared.”

The study also indicates that Skhul 1° was buried in what is interpreted as a mass grave, where the dead were buried with offerings. This indicates a sense of group belonging and respect for children, as well as possible early territorial behaviour.

“Contrary to the prevailing model, the earliest known funerary practices involving burial cannot be attributed exclusively to Homo sapiens with regard to Neanderthal“, says the study.

“For many years, we considered the cemetery to be a very recent invention of human culture,” explains Hershkowitz. “The cemetery means social stratification, belief in life after death, and many things about human culture, its nature, its beliefs, its psychology.”

“And here we have to realize: we’ve already had this for 140,000 years.”