The battle took place about 25 years before Christ. The Romans were entering the Iberian Peninsula and the imperial forces were fighting against the peoples of the north, with the resistant Cantabrians and Asturians fighting against the power of Rome. Emperor Octavian Augustus personally participated in the conquest of that region and poured a large part of his resources into it. The invading force ended up subjugating the indigenous population in bloody battles, as happened in the Siege of La Loma, in the present-day city of Santibañez de la Peña in Valencia, at the foot of the mountains. There, according to a group of researchers, the Romans captured the fortress of Cantabria and left a warning for other tribes on the occupying wall: they had placed the head of one of the fallen. The skull was found in the remains of what is believed to be a landslide, and since the rest of the skeleton did not appear according to forensic studies, the terrifying hypothesis, which is believed to have been copied by the Romans from indigenous villages, has been strengthened.

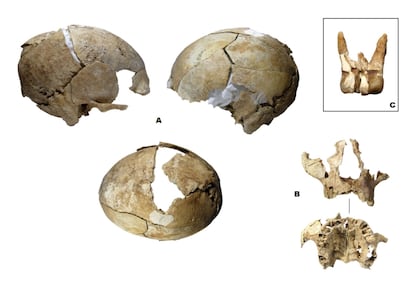

The study, published in the University of Cambridge’s Journal of Roman Archeology, describes what wartime was like in the north of what is now Nathia. The authors state that the Cantabrian Wars took place between 29 and 16 BC and pitted Rome against the ethnic groups that inhabited present-day Asturias and Cantabria as well as the northern regions of Valencia, Burgos, and León. In this period, Octavian Augustus insisted on attacking the Celtic resistance with the best of his forces, and went personally to control the strategies. His forces were hovering over the Cantabrian group at the site of La Loma, where signs of the invading attack can still be seen and where numismatics confirmed this foreign presence. Archaeologists working in these areas were examining the remains of buildings when they found the remains of a skull, broken into several fragments, but with no other bony elements around: there was a head but no body.

The analysis then began under the idea that the Romans, something they did regularly during their empire and which is thought to have been borrowed from earlier peoples, placed the head of one of their victims on the fortress wall to frighten potential rebels or vengeful people. The project’s physical and forensic anthropologist, Silvia Carnicero, describes the process of studying the skull and noting “the cause of all the fractures” as “complicated.” Their work revealed that they were probably due to collapse. The “wall niche”, where the warriors placed it, collapsed at some point and the stones and blocks of the wall broke the bones. Since they did not find any other pieces of the skeleton during the excavation, they concluded that there had been a decapitation and that the head had been used for those specific purposes.

“When it was reconstructed, we saw suspicious injuries, but it had changes on the surface, on the face, which indicates its exposure to weather factors, and weather phenomena that leave marks on the bone and are changed, but if buried they do not happen,” the specialist says, without knowing the exact cause of death. Carnicero does not rule out the presence of a shaft at the base of the skull, in the part of the foramen magnum, but he is “very disturbed” and does not dare to confirm that the head was stuck as in the movies or as recorded in the Aztec civilization. “They were common activities in many cultures,” says Carnicero. “Just as there was cannibalism on subjugated peoples, exposing an enemy’s skull to scare away their friends is not unusual.”

The anthropologist adds that there are no similar cases on that northern coast, but there is similar evidence in the Mediterranean: “It is another basis for the importance of the discovery, as it shows a practice associated with a larger number of peoples.” This area north of Valencia is also characterized by fruitful excavations revealing the presence of Roman camps during different periods, or several thousand years ago, evidence from the Neolithic period unpublished in Europe due to its great quantity and diversity.

The document published by Cambridge states that “direct dating of the human head was carried out using AMS radiocarbon” and that “part of the basal or palatal part of the skull was sent to the Beta Analytical Laboratory in Miami (USA).” From the examination, they concluded that 95.4% of the bones dated to the period between 171 BC and 4 AD, which corresponds to the years in which they suspect the siege occurred, around 25 BC. Furthermore, the individual was approximately 45.2 years old, with a range of 32 to 58 years, and was probably male. Scholars explain that Roman legions “were accustomed to exposing the entire corpses of defeated enemies and parts of their bodies, including their hands and, above all, their heads.” For example, the Column of Trajan (born in Iberia) in Rome, where if you look carefully you can easily see heads hanging on pikes or pegs, although it is known that they were also tied to ropes on walls or other items.