It has allowed unprecedented genomic analysis Reconstruction of biological origin Among those who practiced one of the most distinctive funerary rituals in southern China: LI called Hanging coffins or “pending funds”. The study published in Nature Communications, Analyzes DNA Of the 11 ancient individuals associated with these pockets, 30 are modern genomes of organisms Po village And four individuals from wooden boxes carved in Thailand. Their conclusions show that the current Po Retaining a large portion of the genetic lineage Among those who deposited their dead in coffins suspended on cliffs, A A practice documented about 3,000 years ago.

A distinctive funerary tradition in southern China

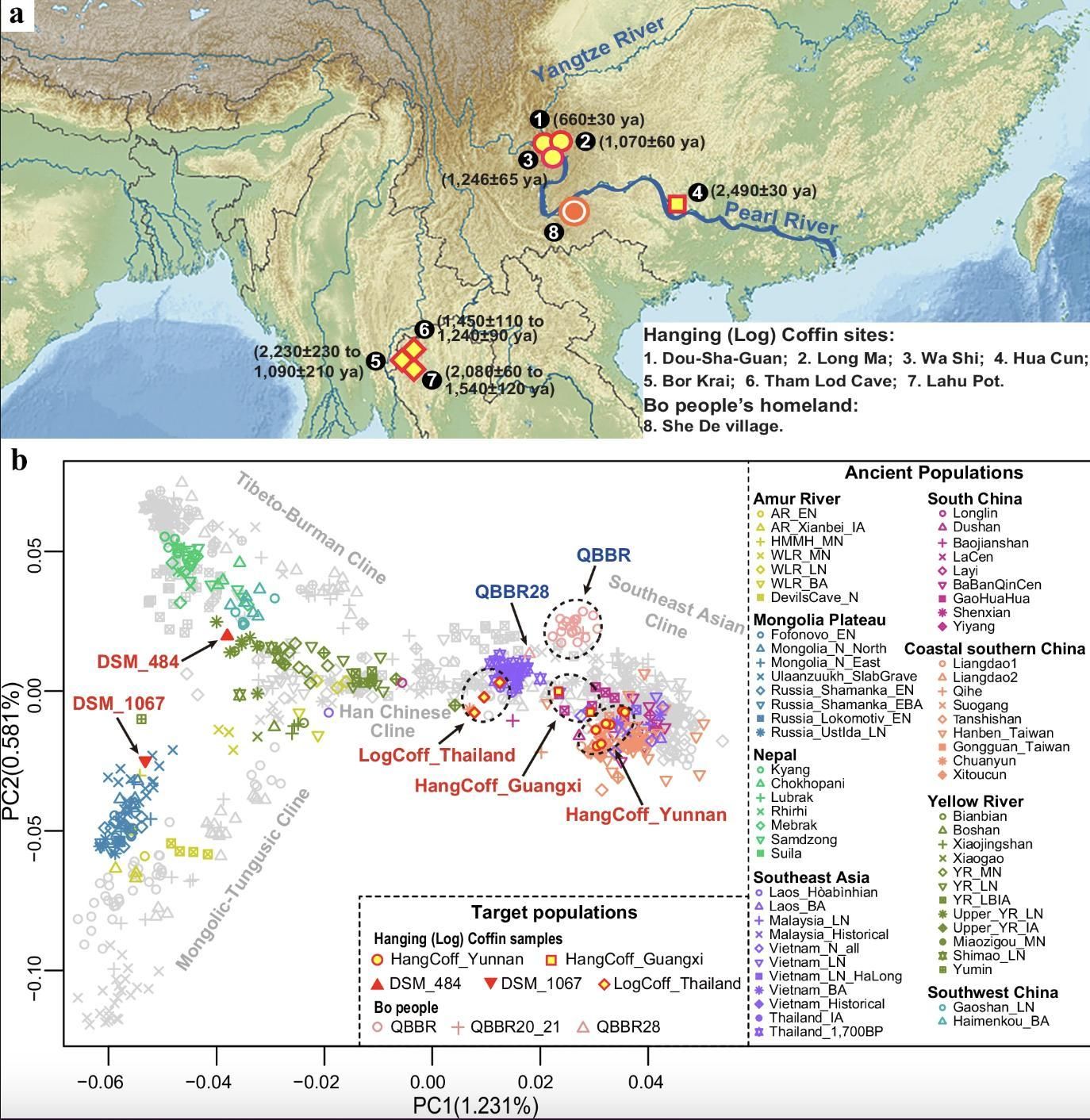

Hanging boxes are one of Asia’s most distinctive funerary traditionswith a presence in China, Southeast Asia and some Pacific islands. In southern China there are hundreds of enclaves associated with this practice, to which historical records are linked The Bo people, a community that has practically disappeared from records After military campaigns Ming dynasty. However, until now, there has been a lack of solid genetic evidence proving the relationship between ancient practitioners and their possible modern descendants.

The study seeks to identify the populations from which hanging chest practitioners came, determine whether there is genetic continuity with present-day Po, and place this tradition within the demographic framework of southern China and Southeast Asia. For this, The team used population mixture modelsAnalysis of genetic drift and comparisons with large-scale ancient DNA databases.

Connections with Neolithic southern China and long-distance contacts

The results reveal a complex genetic pattern. Most individuals associated with hanging boxes show associations with Neolithic inhabitants of the southern coast of China and with historical speakers of the Tai-Kadai and Austronesian languages. Study too He discovers the basic structures that characterize the Yunnan and Guangxi groups, especially those close to present-day Pu. In contrast, two individuals from Jeb Wa Shi (DSM_484 and DSM_1067) show contrasting profiles: one shows associations with Farmers From the Yellow River and Tibetan communitieswhile last Associated with Inhabitants of Altai and North AsiaReflecting long-distance communications about 1,200 years ago.

The team also combined the DNA of four individuals from carved wooden boxes in Thailand, a different regional type of ritual. These represent a mixture of Huabinhian hunter-gatherer ancestors, Yangtze farmers, and a notable contribution from Yellow River people. Its genetic proximity to communities in Yunnan and Guangxi suggests a broad cultural and biological network between southern China and mainland Southeast Asia.

Current Poe: A direct genetic effect of ritual

A comparison with 30 modern Bo people genomes provides one of the study’s strongest conclusions. Demographic models show this Between 43.4% and 79.3% come directly from their ancestors From ancient practitioners Yunnan hanging boxesalong with Between 20.7% and 56.6% Of lineage related to Haimenkouan Early Bronze Age site in southwestern China. This combination fits with the well-known history of Pu, which was characterized by political pressures, forced displacement, and loss of autonomy during the Ming dynasty.

Diverse rituals, with multiple cultural and genetic contributions

Far from confirming the connection between Poe and the hanging boxes, the work makes it clear The rituals were not homogeneous. Its expansion is concerned Cultural exchanges Sustained between different communities in southern China and, at specific times, contributions from the north. These mosaics explain their persistence in remote areas and the regional variations documented in the archaeological record.

The study establishes the first comprehensive genetic framework for understanding the origin of this funerary tradition and its spread in Asia. Combining ancient and modern DNA places this phenomenon in a broader context, linked to late Neolithic population movements and interactions between communities on the southern coast of China and Southeast Asia. For the authors, these developments open new avenues for investigation of other funerary practices in East Asia, which remain genetically poorly documented.