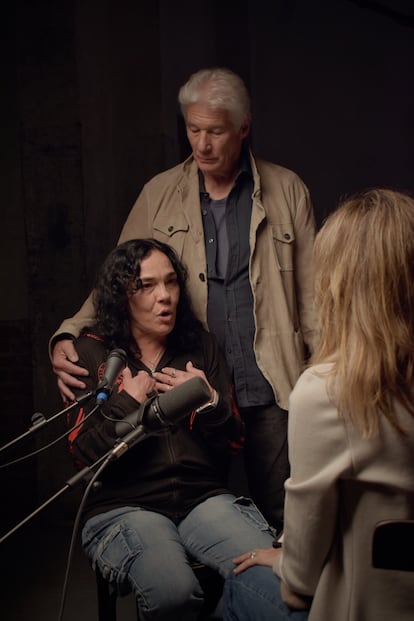

Pepe, 66, points to the entrance to the store where he used to sleep rough, the same place where he was beaten one night and where he pondered for days whether it would be better to die. It is located on the same Madrid street (Bravo Murillo) where he had a bar for 20 years. “I closed my doors in 2019. I started working delivering newspapers and food for a French company, but the pandemic came and I lost both jobs. When I ran out of money, they kicked me out of the rented apartment I was in, and I came to this corner. I didn’t say anything to my family, I wanted to solve the problem on my own, but once you’re on the street, it’s very difficult to get out. People I knew when I was at the bar passed by, who asked me for help, but many looked the other way,” he said. They pretended they didn’t see me.” Pepe is one of the four protagonists in the documentary that actor Richard Gere and his wife Alejandra have just presented with the entity Hugar C: What no one wants to see. The four have completely different profiles, which shows that in so-called homelessness, which affects 37,000 people in Spain, according to the entity’s calculations, there is no profile. EL PAÍS spent a day with them. This is your story.

First night on the street

“The first time my mother threw me in the street, I was 12 years old,” says Mammen, 54, from Malaga, from the Los Girasoles neighbourhood. “I remember walking around at night, very scared, near the school. Some children saw me, brought me blankets and started singing and playing the guitar until I stopped crying.” He has spent more than two decades homeless.

Jaffe, 52, says everything started going wrong when he separated from his son’s mother. “I had a mortgage, a pension to pay, two jobs, but it wasn’t working out for me. When I saw myself sitting in a bank, with nowhere to go, I couldn’t believe it. I thought: ‘How did I end up here?’

Later, a 52-year-old Senegalese, says he found himself on the street because of a scam. “I studied economics in Paris and worked in Brussels with European Commission projects for least developed countries. I speak English, French, Spanish, Flemish and two African languages.” He says some American friends asked him for help investing in Spain, but they did so with a fake check. “While the investigation lasted four years, I had to hand in my passport and go to court every month. In Spain, I didn’t know anyone, so when my money ran out, I ended up sleeping in a tent in a park. I was so afraid, I didn’t know what to do…”

Later continues: “You’re out on the street, in the open air, but in some ways it feels like you’re in prison because you completely lose control of your life. Anything you used to do without thinking, mechanically, like showering, eating breakfast, going to the bathroom…suddenly becomes very complicated. Ever since I felt embarrassed to beg at the supermarket door, to get some money, I would go on market days to help unload the trucks or I would point out free spots in case someone gave me a coin to help them park the car.”

“One season, I lived in a cave in Malaga, among rats,” Mammen recalls. “At that time I was working as a caregiver for an elderly person, so I would get up and go down the hill to go shower at the Red Cross and go to work. When I finished, with all my sadness, I went back to the cave.”

Pepe talks about places in Madrid where there are fountains – “less and less” – and public bathrooms and showers. “My obsession was shaving and cleanliness,” Jaffe recalls. “For me, the way they saw you was more important than what you ate because you discover that you can go a week without putting anything in your mouth and nothing will happen to you. I worked at many things, to dress up: as Santa Claus, as a sausage, as a vampire, in the circus…” Jaffe recalls.

Worst moments: rat poisons and sexual assaults

“In the street,” Pepe explains, “you learn to know people as you see them. There are very good ones and very bad ones.” “Those who hit me were four young children. They were coming out of a nearby nightclub, threw their cigars at me and then kicked me. From that moment on, I set an alarm on my phone to wake up before the disco closed and go away for a few hours, so they wouldn’t see me.”

They almost killed Javi. “An old woman in the neighborhood brought me some lentils one day, and when I tried them, they tasted strange and I was afraid that the woman would be poisoned. I mentioned that to another girl who passed by where I was often and worked in a laboratory. She took it for analysis, and it turned out that it had rat poison in it. I discovered that when the woman returned, the police approached her, which the girl reported to the laboratory, and when they started asking her, the older woman said, “We have to get rid of this scourge.” I think I was not right because I do not understand that you want to harm someone who does not You even know him.

Latter’s worst moment was when he fell ill. “I had severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and after doing some tests, they found lung cancer, but the oncologist told me that on the street I couldn’t receive chemotherapy and radiotherapy because it would kill me. I needed to eat well, rest… so that I could endure it.”

It is difficult to point to a worse moment in Mamen’s life. At 17, she became pregnant in a rape and married her attacker to escape her mother, who she says, when she was a child, tied her to the bed when she went out and then beat her for defecating on her. Her first husband was a hashish dealer. Her second partner abused her. The three ended up in prison. “In prison, they took my little daughter from me to take care of her. I never saw her again. Her name is Miria and she is 15 years old now. I think about her every night.”

And when he got out, he slept rough in Malaga, Cordoba, Seville, Jaen, Almeria… “One time, when I was sleeping on the beach, inside a bag, a man came and started touching me. He wanted to rape me, but I managed to escape. While I was in Malaga, two boys put me in a car, took me to an open field and took off my clothes. I still can’t explain it, but I managed to escape. When an older couple saw me, bloody, naked, they threw I had a blanket on me. He took me to his house and called the Civil Guard. I don’t know how to live.

Better: “I felt like a person again”

They are not moved when they tell of the beatings or tricks they suffered while on the street, but they are moved when they remember some kind gestures from the people with whom they crossed paths, some glimpses of humanity among thousands of very long days. “In one of the ATMs I was sleeping in in Malaga, there was a group of neighbors who helped me a lot,” says Mammen. “They would bring me breakfast and if I was sleeping, they would leave it next to me very carefully, so as not to wake me up… I think about it now and my hair is standing on end.”

One time, when Pepe had not eaten for five days and was thinking of throwing in the towel, a woman approached him. “She brought me a stew that brought me back to life, and now when I see her in the neighborhood, we always talk for a while and I mention her. Another time a family sat next to me on the porch and suddenly the girl came up, opened her purse and gave me five cents. That’s when my heart sank.”

For Javi, the best thing that happened to him on the street was meeting his family. “One day, a man said to me: ‘I’m sorry, I can’t help you much.’ So I told him not to worry and asked him if I could help him with something. ‘Well, I have a piece of furniture that I can’t take out into the street alone.’ I helped him, of course, and he wanted to pay me a fortune, but I said no. From that moment on, when his daughter and grandchildren passed by, they always stopped to talk to me. They made me feel like a human being again.”

Javi and Pepe say one of the consequences the street has caused them is leaving them voiceless. “If you don’t use your vocal cords, if you spend a lot of time without speaking to anyone, it atrophies,” Javi recalls. “And in Alicante, where I spent six months, everyone thought I was mute.”

New life

Thanks to the help of Home Yes in cooperation with social services, the four were able to get a bed, a key in their pocket and a mailbox. Pepe explains that coming back to being, to stop being invisible, is not easy. “I had debts to the treasury, and they helped me settle the papers. Thank God, because to give you one you needed three. They explained to me how to request a court-appointed lawyer and the retirement procedures. Once I got a bed, I resumed contact with my family, who resisted me hard because I did not ask them for help. Now I try to help the homeless people I see when I walk.” He tells it in the Mil Delicias cafeteria, where he went every day to drink coffee because when he was on the street they would take it to him. When you walk in the door, waitresses Sheila Gonzalez and Melede Guamo greet you warmly. He wants to sign up for IMSERSO, even though he knows Spain well. “When I was young, I worked for a while installing EL PAÍS awnings in newsstands,” he revealed at the end of the interview.

Latier finished his final cycle of chemotherapy last February. “Now I am fine, the tumor has stabilized, I live in Cordoba with my girlfriend, and if all goes well, I will start working as an interpreter in January. What I enjoy most is the freedom, the routine of having coffee in the morning or taking a shower without having to think about how or where I will be able to do it.”

Mammen says she took training courses as a waitress and to work in a hotel. “In May, I had had a roof over my head for two years. When I noticed the key in my pocket, I pinched myself. I still can’t believe it.”

Javi works as a delivery driver and dog walker. “This key means everything to me because when the people at Hogar helped me, I had already given up. One of the things I enjoy most now is cooking.”

A recent survey of 40 dB. For home yes (1500 interviews connectedIt was revealed that 22.4%, equivalent to nine million people, were forced to temporarily reside in the homes of their acquaintances for economic reasons. And 10.9% (4.5 million) slept in cars or balconies; 10.1% (4.1 million) slept at least one night in their lives on the street and 8.1% (3.3 million) went to some emergency accommodation (shelters). Pepe, Javi, Mamin and Latier insist on a final message: this can happen to anyone. One problem joins another, a bad streak, a shame that prevents seeking help…and once on the street it is difficult to get out. That’s why they agreed to participate in the documentary, even though at first they thought they were joking. “Imagine them calling you and asking if you wanted to be in a movie with Richard Gere,” Pepe says. “But it was true.” Mammen remembers that first time she saw him Beautiful womanHe thought: “What a handsome man and what a good person he seems. How I would like to meet him. And look where…”.