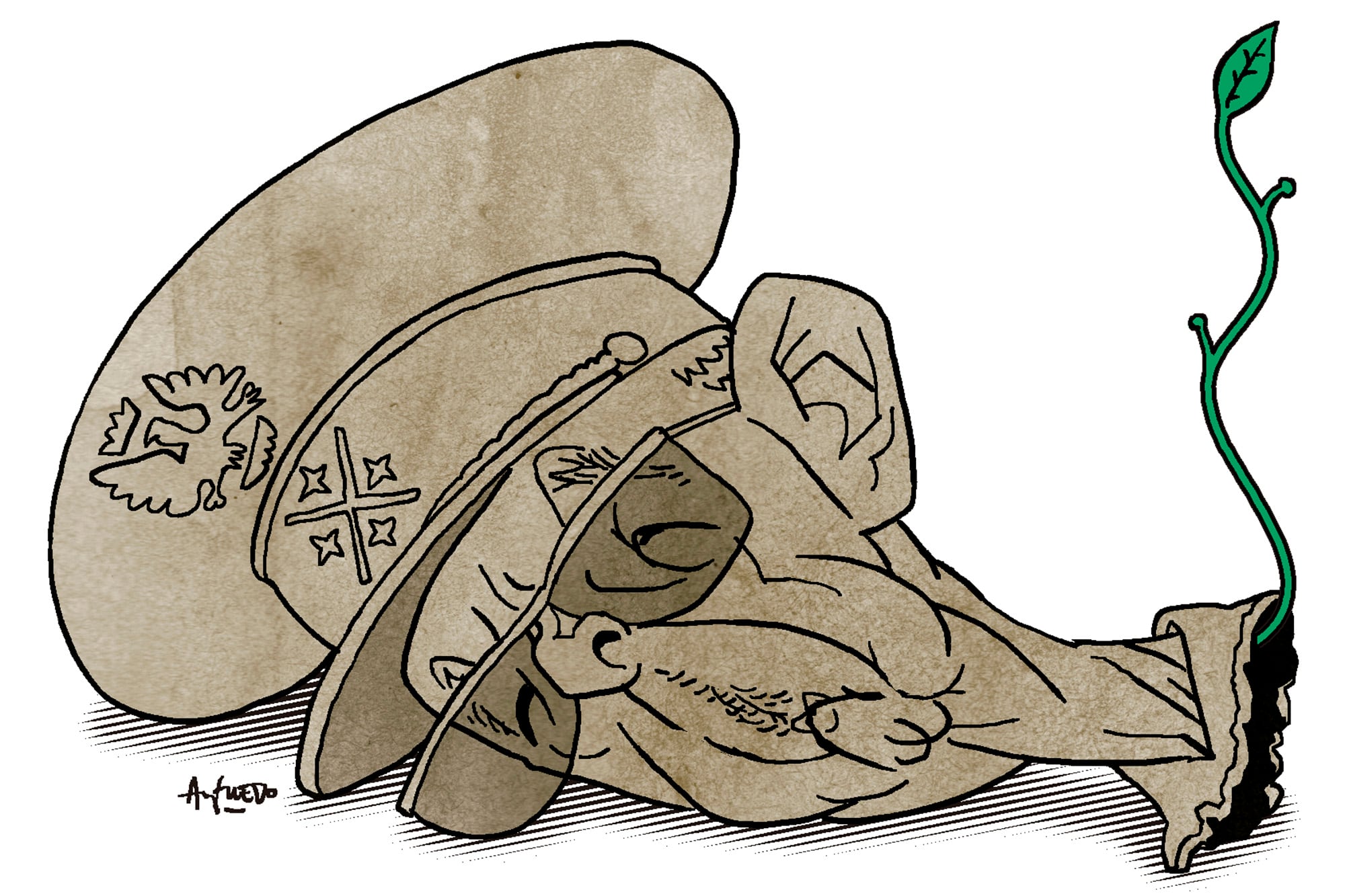

dead Franco, the anger is not over yet. Forty years is an eternity: on November 20, 1975, many Spaniards knew nothing but Francoism, and almost considered that this dark regime of crooks and mobsters was more than just a dictatorship, but the normal state of things. This explains why the most widespread feeling in Spain, on the day of Franco’s death, was neither joy nor sadness; The most prevalent feeling was uncertainty, confusion, and anxiety. No one portrayed it better than Julio Ceron, the unique diplomat who founded the Popular Liberation Front in the late 1950s and paid for his anti-Franco audacity with three or so years in prison. “When Franco died, there was great confusion,” he said. “There was no custom.”

There are those who think that democracy was inevitable in Spain after the death of Franco; Surprisingly, some of the heroes of that period thought so. It is a teleological mirage. Democracy is not a gift but an achievement, so it is not at all inevitable, let alone a surprising Spain without Franco; Indeed, some concerned political scientists, such as Giovanni Sartori, imagined at the time that we Spaniards were not ready for democracy. Our government’s celebratory slogan – “Spain at Freedom. 50 Years” – contains a blatant lie. Franco’s death did not mark the end of Francoism; Nor the principle of democracy. The French movement was strong after Franco’s death, although not strong enough to overcome anti-Francoism. Anti-Francoism was strong after Franco’s death, although it was not strong enough to overcome Franco. Democracy in Spain arose from this nexus of powerlessness.

But it didn’t come right away. What Franco’s death brought was not freedom: it was the beginning of a series of political and social movements eventually known as the Transition, which ultimately culminated in the change from dictatorship to democracy. This historical period became politically controversialNot because our politicians have any real interest in history, but because even the dumbest politicians know that in order to control the present and the future, they must first control the past. This elementary Orwellian wisdom is responsible for the fact that since the party system generated by the transition period disintegrated or seemed to disintegrate in the middle of the last decade, it has entered the political battlefield: the new parties needed to impose a version of the past that was beneficial to their interests, and to manipulate or falsify it at their convenience in order to delegitimize their opponents, whom they rightly considered responsible. The result was the emergence in public debate of a dual and contradictory story about the transitional period, which until then had remained buried in its germs.

As a result Result: There is now a pink version and a black version Transitional. The rosy version, supported by the right and by many of the period’s heroes who yearn to justify their executions, assumes that the transitional period was a period of smooth harmony among idealistic elites, whose inflexible good sense and sense of history promoted the peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy; Supported by the far left and separatists, the black version argues that the transition was a shameful rinse by which the regime par excellence – Francoism – was transformed into a regime of 78, which in essence is not a real democracy but a pseudo-democracy: Francoism by other means. I don’t know if it is necessary to add that both versions are wrong. The truth is that, as all indicators of the quality of democracy in the world show, the transition has generated real democracy, worse than some, better than many, and imperfect like all; It also highlights – and this is not an opinion: it’s a fact – the best fifty years of modern Spain. However, it is no less true that this was an extremely complex period, saturated with moral shadings, political balances, social tensions and violence from right and left, and that although political agreement, historical responsibility and the will to break out of dictatorship and build democracy dominated the ruling class from mid-1976 until the end of 1978, from the beginning of 1979, after the approval of the constitution, political life witnessed unprecedented discord. The barracks, extreme polarization and, at times, suicidal irresponsibility, all culminated in a coup two years later.

That was it The decisive moment. LegallyDemocracy began on December 27, 1978, when the constitution was promulgated after having been approved in a referendum three weeks earlier; Symbolically – that is, in reality – it began at 6:30 in the afternoon of February 23, 1981, in the Chamber of Deputies, when the three politicians most decisive in establishing democracy and who had not believed in it for most of their lives – Adolfo Suarez, General Gutiérrez Mellado, and Santiago Carrillo – decided to risk their lives for democracy. Did Franco’s regime also die then? You don’t have to act interesting: yes, for obvious reasons; There is no need to be naive: no, because the past never passes: it is a dimension of the present without which the present is distorted. The best thing you can do with the past, starting with the darkest past, is to try to understand it: this is the only known way to control it and prevent it from controlling us, forcing us to repeat the same mistakes over and over again. In other words: it is impossible to do anything useful with the future without always having the past present.

As for me, the disgust is insurmountable Death prevents me from rejoicing even in the death of someone as evil and bloodthirsty as Francisco Franco.

Truth: I don’t know what the hell we’re celebrating.