Oriana Fallaci spoke with Pier Paolo Pasolini to L’Europeo in 1966, A Marxist in New York. Pasolini tells him this phrase: “I love life strongly, desperately. And I love the poor and the living.” Pier Paolo Pasolini died in the early hours of November 2, 1975, 50 years ago, on the beach at Ostia, near Rome. They found his body at dawn: destroyed, covered in mud, with car marks – his – marked on the chest, disfigured face. Police arrested a 17-year-old boy, Giuseppe ‘Pino’ Pelosi, who said he killed him “in self-defense” after a fight over sex. It didn’t make sense: there were even witnesses who said they saw the author’s car driven by more people after his death. The case was closed quickly, as if Italy was in a hurry to bury the poet along with the scandal.

Pasolini had just launched Salò the 120 days of Sodom and announce that he was writing a book about power and corruption. Pelosi was convicted, but in 2005, thirty years later, he recanted: he said that three “well-dressed” men had participated in the beating and forced him to take the blame. Since then, the crime has remained a question mark. Pasolini died as he lived: on the border between lucidity and danger. The mud of Ostia was his last metaphor: there was the mud of the body, of politics, of Italy that he was trying to undress. Maybe they killed him for trying to look where no one was looking.

A Violent Life is one of the books that had the most profound impact on me when I was young. For simple and delicate reasons that go beyond the brutality of the language and the misery it portrays. For the tenderness, for example, that hides behind each blow. Through those dusty streets of the Roman suburbs where one discovers, as the story progresses, that dignity does not depend on success or cleanliness, but on the minimal gesture of someone, with nothing in their pocket and with a debt to collect in life, who is still capable of feeling sorry. The novel is about a boy who understands that life can be something else and, at the same time, that it is already late, as Gil de Biedma later predicted: Tommaso Puzzilli teaches that redemption exists, but it arrives when the world has stopped listening. How much goodness can a society support without rotting?

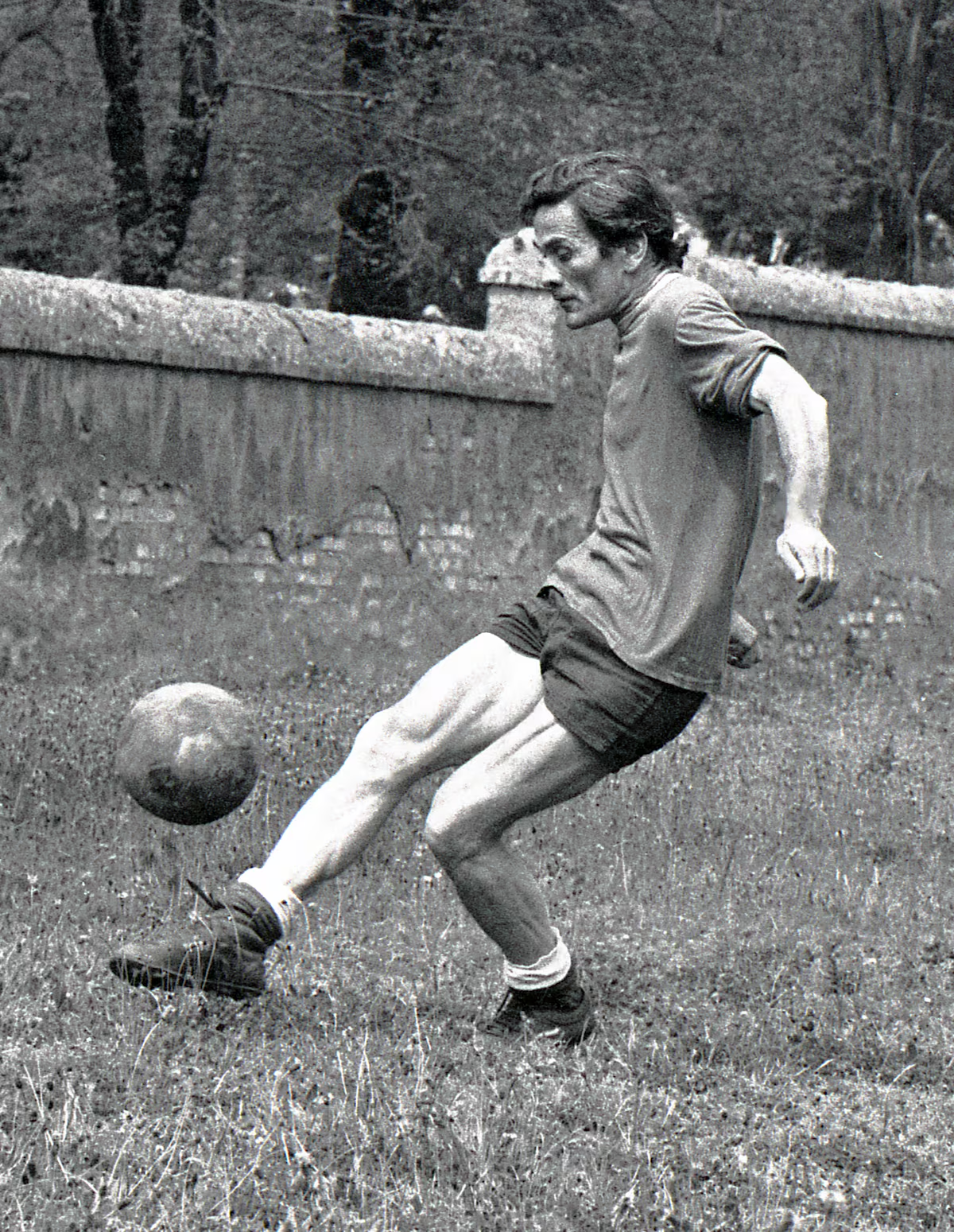

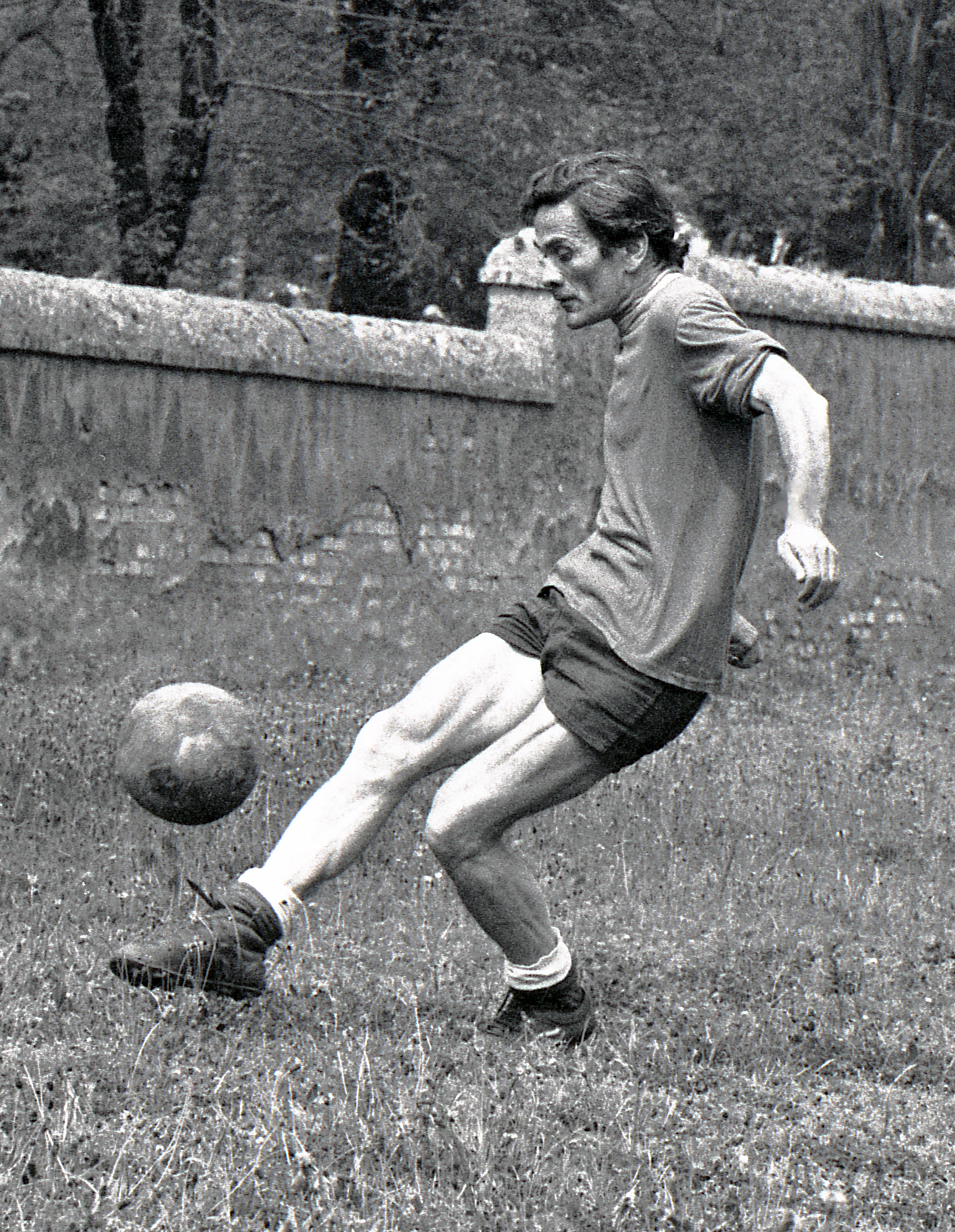

He was a filmmaker, writer and football player, three professions that we can all have just by going out into the street. I played for hours as a child, I played during shooting, I played until the end. He said that football was a language, a communication tool in which it was necessary to distinguish between the unpredictable geniuses (poets) and the armed builders of the game (prose writers). So I wanted football as a secret language. In the mud of open fields and stadiums full of workers, he observed that it was the only liturgy that still united Italians. He said each goal was a poem, an emergence of popular beauty amid modern boredom. Football was not an escape like for so many, but an act of collective intelligence: a choreography where the people, without knowing it, wrote their own epic. Between ritual and grammar, Pasolini found in play the last innocent form of community, the poetry of the body before television.

A stunning phrase to reread: “I remained in the idealism of high school, when playing with a ball was the most beautiful thing in the world.” And a book to recommend: Football according to Pasolini, by Valerio Curcio (translation by Ernesto C. Gardiner and prologue by Toni Padilla, publisher Altamarea).