New excavations at the large Roman villa located in what is today known as Civita Giuliana, just outside ancient Pompeii, offer new insight into Roman social history. The image of the slave as a starving and malnourished worker … it cracks. Archaeologists at the Pompeii Archaeological Park have uncovered a telling paradox: in the rooms where slaves lived and worked – the space reserved for them within the city – these men and women, on some occasions, ate better than many of the region’s free citizens. The contrast is brutal.

The excavations, published in the E-Journal degli Scavi di Pompei, shed light amphorae full of beans –one of them half empty– and a large fruit basketprobably pears, apples and mountain ash, foods rich in vitamins and proteins. Added to this is the reconstitution of the establishment’s annual consumption, which reaches a revealing figure: 18,500 kilos of wheat necessary to feed nearly cfifty slaves who lived and worked there. A huge sum intended exclusively for them, while many free families in Pompeii had to resort to begging to survive.

Written documentation had already revealed this contradiction. The Romans defined slaves as “speaking instruments» (“instrumentum vocal”), a legal category which assimilated them to work tools. But, In agricultural towns like Civita Giuliana, these “instruments” could be worth thousands of sesterces.reference currency of the Roman Empire, and losing them due to illness or malnutrition represented an intolerable economic risk.

The discovery now materially confirms that in addition to the basic grain-based diet, the owner introduced more nutritious foods to strengthen the health of its workers. Without these supplements, infections, vitamin deficiencies, and loss of physical strength were common among those who performed strenuous work in the fields, guided animals, or participated in the grape harvest.

The director of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, sums up the moral and economic paradox of the discovery: “They were treated like machines, but the line between slave and free continually blurred: sometimes slaves ate even better than so-called free people“. The archaeologist also recalls that the Stoic and Christian idea according to which we are all slaves or free in a deeper sense was born from this daily contrast: beings deprived of rights could benefit from a superior diet than poor citizens who depended on alms from the powerful.

Calculated exploitation

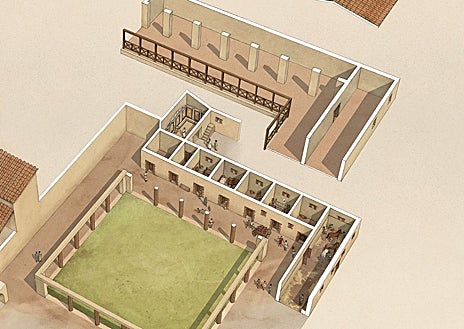

However, living conditions in the slave quarters were difficult. The cells measured just 16 square meters and contained up to three beds per room. On the ground floor, the excavations made it possible to identify numerous remains of rats and mice, which explains why food was stored on the upper floor: protecting it from parasites and controlling its distribution was essential. Researchers hypothesize that the most trusted slaves might sleep there, responsible for monitoring the food and rationing it according to the owner’s orders. Food was therefore not a privilege, but a tool of discipline.

Archaeologist Antonino Russo summed it up bluntly: “Slaves are very expensive. and the investment had to be protected. “The richer the owner, the better the slaves eat.” His sentence reveals the essential logic of the system: the food found in Civita Giuliana is not a sign of well-being, but of calculated exploitation. Feeding slaves well ensured longer days and better performance.

A majestic agricultural village

Civita Giuliana is located in a strip of majestic villas dedicated to the production of wine, oil and other agricultural products. In recent years, discoveries of great importance have already appeared there, since a ceremonial chariot decorated in bronze to the exceptionally preserved slave quarters. The new discovery allows us to reconstruct with unprecedented precision the daily lives of the invisible workers who made this wealth possible. Not only did food remain important, but also the spatial and social organization of enslaved personnel, with their internal hierarchies, control systems, and specific functions.

The excavations also made it possible to recover elements linked to agricultural work: the outline of a double door, tools and what appears to be the upright of a plow. These are pieces that describe a complete economic mechanism, where good nutrition for the worker was as necessary as the conservation of utensils.

The official press release from the Archaeological Park highlights another key point: social comparison. While the city distributed tons of wheat and fresh produce to its slaves, many free families in Pompeii did not have the bare minimum and resorted to help from patrons or benefactors to survive. Legal freedom alone does not guarantee a decent life. This contrast brings a profoundly human nuance to the investigation: extreme inequality was the social fabric of the Pompeian world, and the slaves’ diet reflects not improved conditions, but the economic downside of an unequal system.