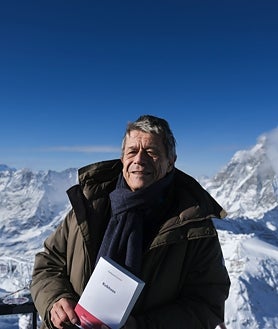

We reach the Little Matterhorn after climbing the summit of Bianche Laghi, near Breuil-Cervinia, a region of the Italian Alps known for its mountain lakes and which is part of the Mont Blanc route. More than three thousand meters from … high up, nestled at the top of the Matterhorn and between the Aosta Valley, the writer Emmanuelle Carrère poses in front of the cameras. He is holding his novel “Kolkhoz”, who has just received the Grand Continent Prizea recognition which distinguishes works which offer a relevant look at Europe. Installed on the mountain of oneself, Carrère reaches the summit with this hybrid between fiction and non-fiction.

“Kolkhoze” is an exercise in family archeology. It begins with the meeting between his mother’s future parents and plunges into a past marked by wars, exiles and cultural divides. The young German-Russian protagonist comes from an aristocratic lineage collapsed by the Revolution and Stalinism, while her partner represents post-war bourgeois France. This shock allows Carrère to explore the turbulent Europe of the 20th century: forced migrations, loss of identity, poverty of stateless people and the weight of history on private life. Yours included.

The title – “Kolkhoz”, a reference to Soviet collective farms – symbolizes the political context that shapes his family’s biography. It is not just a place, but a system that determines destinies and fractures genealogies. The novel connects this historical landscape to the present of the writer, who reconstructs the life of his mother to understand her character and her aspiration to be recognized by France. The plot is set in the context of 20th century European history, where identity, memory and affections come together. The ascent path is marked by the Carrère point of view: it is the massif where this exploration takes place.

mountain range alone

For Carrère, the self is as natural as it is familiar. For him, the novel is what serves an exploration. He does not understand that “an author is criticized for speaking about himself”, nor that it is discussed whether a work is fiction or non-fiction. “The novel is something incredible, because it has no definition. When we tell something about life, it is closer to non-fiction. That’s the advantage of reality: the freedom of what we do with it,” he explains. The self is its territory, the slope on which it advances or the summit to which it clings through writing. Its circumstance is enough for it.

— This prize rewards a view spanning an entire continent. Do you feel like a European writer?

— I am a French writer who writes in French.

— Also European.

— I am French because my language is French. That’s the only thing that matters.

— In your books, Europe embodies part of your thinking.

—The only thing I live by is my language. There is no European language.

Distance from Russia

Emmanuelle Carrère was born in 1957. She grew up in an intellectual environment marked by her mother, a historian and academic. Hélène Carrère d’Encausse. This background of family memory and historical debates appears in his work. He began to write novels like “El moustache”, but soon his writing moved towards a hybrid genre between documentary research and introspection. This mixture reaches its maturity with “L’Adversaire”, a shocking story of the Romand affair. Since then, he has explored the lives of others and his own with a constant obsession with the truth in books such as “A Russian Novel”, “On the Lives of Others”, “Limonov”, “The Kingdom” and “Yoga”.

The novel “Kolkhoze”, for which he received the Grand Prix du Continent this week, revolves around the death of his mother. That was the trigger for the book, but the process is longer: grief led to a deeper dig. Carrère was scheduled to travel to Moscow on February 24, 2022, at the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, for a film project. The war changed everything: he canceled the trip then returned to report and observe the situation for himself. This experience appears in his vision of Russia.

After the invasion, Carrère modified his traditionally more sympathetic perception of the country: “We can no longer love Russia, but we can love certain Russians.” This crack is seen in the “Kolkhoze”. In his research, he mixes the history of his Russian and Georgian ancestors with events of the 20th and 21st centuries. The invasion of Ukraine is not a central theme, but it is an essential historical context that contextualizes his thoughts on Russia, the family and European identity. Even if he wants to define himself as a writer of his language, his universe tends towards hybridization: like the Alps, something larger runs through him and he tries to carve it out through his literary being, which touches everything he touches, including journalism. This is why, sometimes, it itself becomes a literary genre.

— In you live together a novelist and a journalist.

— I do journalism all the time. It’s something I’m really passionate about. I write reports exactly the same way I write books. The only difference is that I have an editor. It’s like he’s a fiction writer who writes novels and also stories. I don’t write stories, but I write reports. I write the same thing as in the books.

—To what extent does journalism influence those who create fiction?

— I consider journalism to be a literary genre. I have the chance and the luxury of being able to produce reports with the same freedom as a book. That’s for sure. “I am very aware that this is a rare privilege.”

“Despite everything, understand”

The alpine ascent with Emmanuelle Carrère ends at the summit of the Petit Matterhorn. There he gives his acceptance speech for the Grand Continet prize, a reflection on the way of looking at the world. Or perhaps the realization that he himself is the pinnacle of a way of understanding the world. “Today there are two ways of seeing things: one relatively optimistic and the other radically pessimistic,” he says. “Optimists believe that we are going through a phase of tragic chaos that has already happened and that humanity will overcome. Pessimists believe that such chaos has never existed and that this is not a phase, but the end. “The main and, in my opinion, only argument for a relatively optimistic approach is that, since the dawn of humanity, there have always been people who have said the same thing, that it was better before and that the end of the world was imminent,” he says, holding a sheet of paper in his hands.

The sky is impeccable, the blue of a freshly polished window. And there the victor goes on, stating the world. “A great Latinist, Lucien Jerphagnon, wrote a very funny book which is an anthology of these distressing predictions throughout Roman history. “Nothing new under the sun, that would be reassuring,” he said. “However, it seems obvious to me that no, it was not always this way. Although we view human beings’ propensity to become anxious as a constant, their reasons for becoming anxious are new and unassailable. You don’t have to be very smart or very knowledgeable to list them. First of all, there are eight billion of us on Earth and that’s too many. The other reasons for anxiety flow from there. First the ecological disaster, now irreversible. Second, the migration crisis: more than half of the planet is becoming uninhabitable, so the inhabitants of this half want to go and live in the other half.

In the middle of his enumeration towards the Apocalypse, Carrère constructs two more steps. “Third, artificial intelligence, which is devouring us, but we still don’t know how or to what extent.” And finally the fourth, which serves as a ledge to fall from the cliff, downhill, “which is the end of democracy, the end of all our values, but it is less important, because it only concerns us and, apart from us, no one seems to consider this as a great loss”. The dizziness of his words does not lie in the height from which it is spoken, but in the imminence of his diagnosis.

“I said you don’t have to be very smart or very informed to be aware of all this. But still, being very smart and informed helps. We don’t really know what, but it helps nonetheless. This helps to have a broader and more precise awareness. This is called historical consciousness. Even in the situation of the frog who simmers and only discovers little by little what is happening to him, it is still good to understand. At an altitude of more than three thousand five hundred meters, Carrère ends his speech to applause.