“It was the year 92. We hadn’t had it for years, until it showed up again. When we were at our calmest. In three days, around a hundred pigs died. In one week, 1,500. We had to sacrifice them. At the foot of the grave. Then we burned them and buried them. … ashes with quicklime. “It was the worst moment of my life.” Antonio Bueno has been a pig breeder “since he was born,” he jokes. Like so many others, he had to face African swine fever at a very young age. In his farm, located in the municipality of Villalba de los Barros, in Badajoz, the last major outbreak of the disease that devastated the pork sector of Extremadura for more than three long decades was detected.

The province of Badajoz has in fact opened the door to the disease throughout Spain. In the late 1950s, the focus shifted to Portugal. It entered the Iberian Peninsula because in the neighboring country contaminated remains from the catering of an airplane from Angola were fed to pigs. Once on Portuguese territory, it is believed that it was the smugglers, who freely roamed the capital Badajoz, who ended up introducing the disease into Extremadura. This opened a period of uncertainty for the pig sector throughout the country, but especially for Extremadura, which continued under “red band” restrictions until the 1990s. In the first two months alone, 50,000 pigs were slaughtered in the region.

Extremadura was then, as today, the cradle of Iberian pork. There were practically no intensive pig farms. Almost everything was pork montanera. And in this scenario, the disease is unstoppable. The animal is in constant contact with other living beings which, in one way or another, can transport contaminated particles. Once a pig was infected, it was impossible to save the farm. It doesn’t matter whether it was due to illness or sacrifice, because if one of the animals was infected, the entire farm was sacrificed, including some neighboring ones, as Enrique Muslera, who in the 80s was general director of livestock breeding of the Junta de Extremadura, in the government of the socialist Rodríguez Ibarra, recalls: “It was terrifying, they were horrible years, there were many people who went bankrupt.”

Muslera also explains that for years the government, which paid for the slaughtered animals, did not distinguish between Iberian pork and white pork: “They were worth the same, while the value of Iberian pork is obviously much higher.” These are all ingredients which, together, have led the sector towards a situation of real catastrophe. Antonio Bueno, the breeder who faced the last major epidemic, estimates that he would lose “around €70,000 from here”.

Thousands of families in ruins

José Carretero, son of a breeder, who saw how his father suffered from the ravages of swine fever, decided to become a veterinarian when the disease hit hardest. He was aware of the “ruin” that this meant for thousands and thousands of families: “When we had a positive result, we did not know how to tell the breeder because things became very ugly, either because he was not insured or because the compensation was minimal. “What many did was try to sell the animals. » It is estimated that in municipalities like Higuera la Real, 8,000 pigs were sacrificed. This could have been the end of Extremadura Iberian pork as we know it. Today.

“To talk about the plague was to talk about the virus. “It was worse to say we had sick pigs than to say someone was dead.”

Gonzalo Llorente

Rancher

The mortality rate was 100%. “Talking about the plague was talking about the virus, it was almost worse to say that one of the inhabitants of the town had pigs affected by the plague than to say that someone had died,” explains Gonzalo Llorente, who took his first steps as a breeder, with his father, in front of ASF.

He remembers that he was afraid that his father would tell him that “a slut was bad”: “It was a disaster, it was being at home in a bad mood, going to the fields without wanting to and thinking about stopping, but you had to continue, you couldn’t do anything else,” he laments. He, like many other breeders, cannot prevent very dark memories from flooding into his memory, years which were real suffering for those who devoted themselves to pigs. The way they died was also particularly traumatic and unpleasant. Health authorities shot and killed the animal, but the worst happened later: “I have an image in my mind. There were over 100 pigs. When you watched them burn, you felt like they were burning your life’s work. “I have the reflection, the exact spot where they burned and I can’t get it out of my head.”

“I had to fight, that was the biggest challenge. “We are forcing ranchers to redesign their farms to make them safer.”

José Marín Sánchez

Veterinarian

This farmer, who has his farm between the municipalities of Badajoz, Oliva de la Frontera and Jerez de los Caballeros, one of the areas most affected by the disease, admits that when he heard the news coming from Catalonia, with the death of infected wild boars, he “started to tremble”: “What we experienced does not fade easily. We always say, joking, that if the plague came back, we would be done with it. Now we think about it really. It would be great. “It’s almost better not to think about it.”

In the same vein, Antonio Bueno says that his wife always tells him that “they will continually live in a stressful situation”: “We will be afraid all our lives that it will come back.”

It is not for nothing that Extremadura would be today, as then, the region most likely to suffer from the consequences of African swine fever, precisely due to the nature of the agriculture practiced in the region, mainly in the mountains. The autonomous community produces around 40% of the acorn-fed pork in all of Spain. During the last mountain, more than 580,000 acorn-fed pigs were slaughtered in Extremadura. Under the D.OP. Dehesa de Extremadura, the sector is a real economic and social engine for an eminently agrarian region.

Grazing encourages it

José Marín Sánchez is currently president of the College of Veterinarians of Badajoz. In his time, he was part of the teams that fought the disease. He recognizes that this is the “biggest challenge we have ever had” in terms of animal health and admits that he feels real “panic” about the possibility that the disease could progress to other territories and eventually reach Extremadura, where grazing systems would be the perfect recipe for the disease to survive, as has already happened for years.

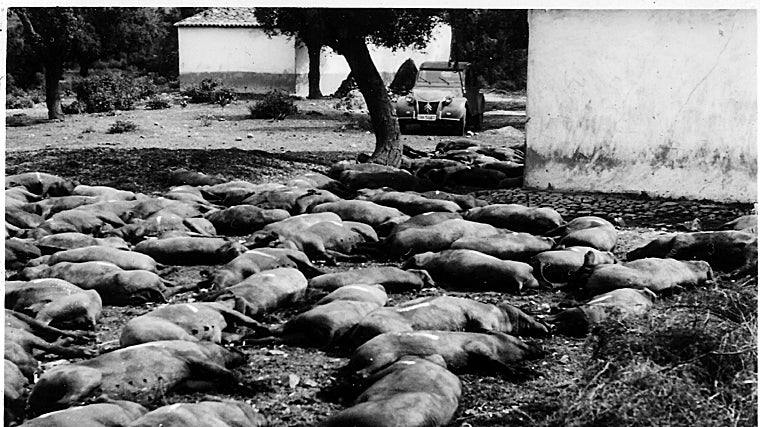

A farm in Badajoz with dozens of Iberian pigs killed by the plague

He explains that the situation, in the veterinary sense, has changed radically since then. Let us remember that the campaign carried out in Extremadura against “the carriers” of the disease ended up being a success based on two main pillars. The first was to force breeders to almost completely remodel their farms, which were old, obsolete and favored the perpetuation of the chinchorro, the pig tick. Wooden constructions were eliminated in favor of sheet metal and prevention measures were increased. Vehicles entering farms first passed their wheels through liters of bleach. This was important, according to Sánchez. As much as the effectiveness of the diagnosis: “It did not fail. “We received the samples, they were processed and knowledge was imparted, but this result was going to be massive.” He believes that right now the biggest problem in trying to stop the spread of the disease is something else. He refers to wild boars which, according to him, “are the biggest problem”. He admits, however, that although he tries to be optimistic, “fear” exists.

María Jesús Gómez is also a veterinarian and, in addition, a member of the Regulatory Council of the PDO Dehesa de Extremadura. He therefore knows well the devastating effect that the arrival of African swine fever could have, once again, in Extremadura. She hopes that the epidemic “will be eradicated and will not spread to other communities”, especially because, since 1994, “more in-depth studies, research and diagnostic techniques have been carried out and knowledge about the disease has expanded” to be able to combat it more effectively, but she recognizes that, if it occurred, “it would be a catastrophe with serious economic losses”.

He insists, like his colleagues, that pasture “provides suitable weather conditions, where the virus could survive for long periods”. He claims that since these are pigs on an extensive diet, “they would easily have contact with infected and uncontrolled wild animals, which would mean greater expansion and more difficult control.”

Extremadura pasture presents weather conditions in which the virus could stay longer

In short, it is inevitable that the news coming from Catalonia worries Extremadura. The Government of Extremadura itself has already set to work to double down on prevention and orchestrate joint planning between three different ministries, with the support, in addition, of the hunting sector in relation to the wild boar population. The worst omens for many breeders are back on the table today. Uncertainty, fear, even, as some say, real panic. A feeling that, however, succumbs to a maxim that prevails even more strongly among those who have devoted their entire lives to devoting themselves to the pig sector.

Antonio Bueno summed it up well, from the same farm on which he suffered so much that fateful year of 92: “It’s a job in which you cannot lower the blinds at once, in which you cannot finish everything at once. When I say that I am a breeder out of affliction, my wife tells me no, that I am a breeder out of addiction. Maybe. The only thing I know is that I am a breeder and anyone who is a breeder is a breeder for life. Three decades later, like so many others and despite everything, he is still on the farm.