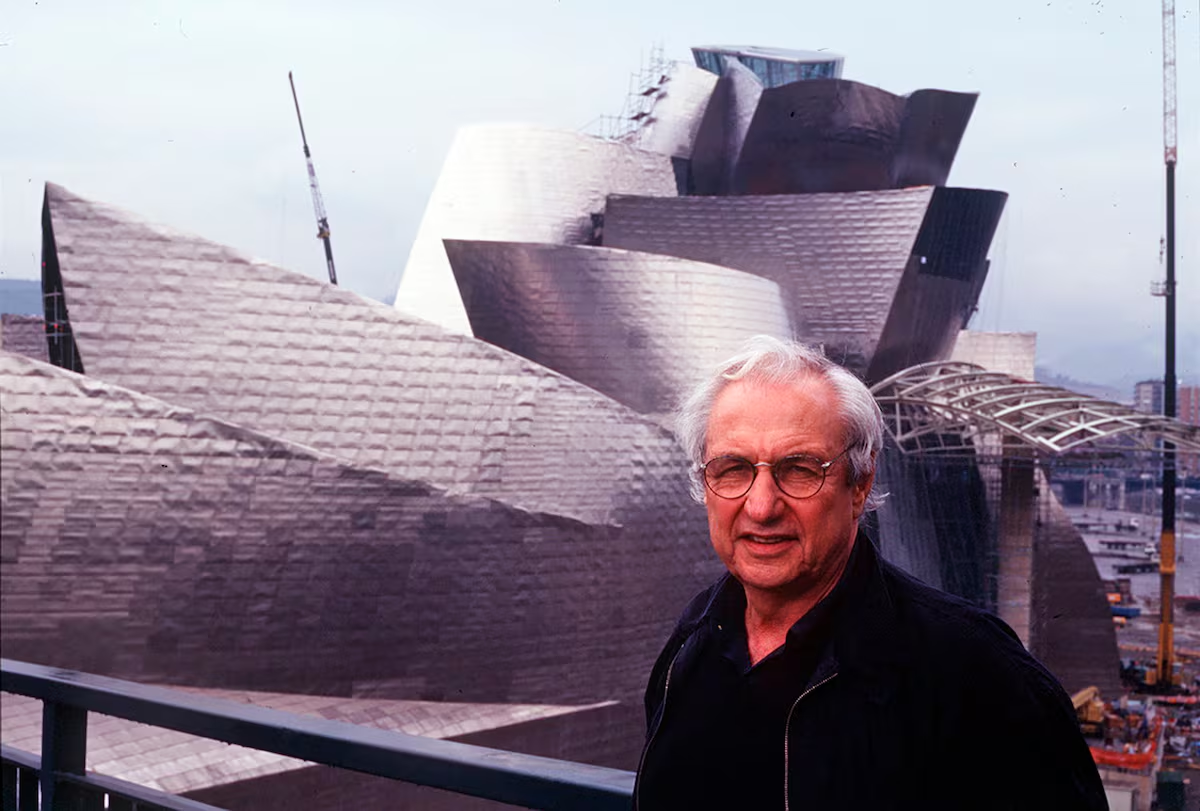

In a classic article on how the “Bilbao effect” and how Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim sparked a story that would spread to cities around the world, published in The guardian On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the museum, the Canadian architect, who died at the age of 96, remembers that a month before the inauguration he had climbed the Artxanda mountain. I looked down at the blazing, shiny titanium creature from above and thought, “What courage do you have for these people?

“It was really like that, holding hands up to your head,” remembers Juan Ignacio Vidarte (Bilbao, 1956), director of the Guggenheim Bilbao from its creation until 2024, Gehry’s accomplice in Bilbao since the first day of this crazy adventure. “He was a very humble person, but at that moment I understood that he had transformed the city forever. Like all good relationships, there had to be something reciprocal. Gehry brought a fundamental element to Bilbao, but I want to think that Bilbao also became an architect.”

This was not the first time Artxanda had a telling effect on Gehry. We could decide that everything was there, in this high place, on one of these green hills which surrounded the city and gave it the affectionate nickname of “el botxo” (el agujero). It was May 1, 1991. The feasibility study for the project to create a Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was underway, as part of the city’s transformation. Although it was known that it must be an important building, a small architectural competition had narrowed it down to three candidates. The Japanese Arata Isozaki, the Viennese Coop Himmelb(l)au and his own Gehry, then a successful 62-year-old professional, are today the designated figure of the star architect who passed through Bilbao and made a toast.

“We invite architects to come and explain the project,” recalls Vidarte. “As part of the trip, we went up with them to Artxanda, because if you don’t control the height, it’s difficult to understand the city. Then the main location that was managed for the museum was the La Alhóndiga building (which today houses the Azkuna Zentroa). But when we went up to Artxanda, Gehry asked what was there, in the place where the river ran. And the museum ended there.”

What was there, on that curve of a brown, pestilential river, was a crane car depot, a pile of stacks of containers crossed by a long railway from the Euskalduna shipyards and the massive La Salve bridge. An apocalyptic scenario of industrial decadence where the city takes a backseat, dodging the barricades and gumdrops of anti-disturbances. Gehry understood that this had to be the epicenter of Bilbao’s transformation. “I understood very well the unique relationship that exists in Bilbao between the city, the river and the green cell of the mountains,” recalls Vidarte. “The gustaba is that hardness of Bilbao, which has largely been lost.”

The uniqueness of the winning project reveals the courage of those who promoted it from the institutions. “Gehry did not present plans, like a cardboard model,” explains Vidarte. “My first impression was to wonder what it was. It was difficult to understand. But I thought very carefully about how Gehry understood the program. Architecture could not limit the space, which should have made it possible to exhibit a 100-ton sculpture by Serra and a watercolor by Kandinsky. And then the project had to have a transformative effect of the place. Captó como nadie the key points of the plan”.

In October 1993, I laid the first stone of a prodigious work. An explosive collaboration begins between Californian architects, New York patrons, strong Basque engineers and courageous young managers who will produce, quickly and safely, a global architectural success. “It was a very controversial project and so it was important to meet the deadlines,” says Vidarte. “The different teams met every four or five weeks. They were divided into two areas of responsibility, which was decisive in overcoming the first suspicions. The work was carried out gradually. The project was not finished at the start of the work. Gehry continued to design the building until 1994. If you use a software of aeronautical design to manage complex curves. This was the first time this had happened on this scale. It was crazy. But as I progressed, things stopped flowing. And it was even a friendly relationship.

For Gehry, this must also be a claim for his architecture, which was then called into question. “This was a subsequent project at Disney Hall in Los Angeles, which had been brought forward when the Guggenheim was commissioned,” Vidarte explains. “But this project was hamstrung by construction and management problems. There was great criticism, most of it directed at Gehry. It was decided that the problem was not the management of his architecture. Here we set out to demonstrate that this was wrong. And for this reason, the industry collaboration that existed around the project was essential. Guggenheim was a way of pretending that Gehry’s architecture was buildable.

The success of the project ended up creating a relationship of affection between the architect and the city. “The taste came, he came to the Rogelio restaurant, which was coming. He tasted the merluza, the green peppers…”, assures Vidarte. “He was a very close person and, even though he didn’t speak Spanish, he won the love of the Bilbaino people. He continued to come to town, the last time three years ago. And for a while I’ve been thinking about moving to live here with his family. I looked at houses in the Mundaka area, in the Urdaibai reserve.”

Vidarte recalls that the work was progressing steadily and that Gehry had not yet decided on the metal material that would cover the surface of the museum. “It was one of his last decisions,” he explains. “On the solarium of the work he installed a structure where he placed different types of sheets. During his last visits to the work, he sat on a slab to contemplate for hours how the light was reflected in the different panels, which in Bilbao varied a lot during the day. One day he read a sheet of titanium and was fascinated by how it reacted to the change in light in the city.”

The complicated problem is caused by the titanium plate

Gehry understood that titanium was very expensive and could not afford it. “But we came to an agreement that we would bid for the work with another material, and if we ultimately managed to get titanium into the hypothesis, we would continue,” says Vidarte. “In the end it was achieved. I think it explains how Gehry faced these decisions in parts of the building that were fundamental and how they related to the place where he was staying.”

This link with a concrete place and Gehry’s ability to integrate himself into a project that transcended architecture was, according to Vidarte, one of the keys to the success of the “Bilbao effect”. “The objectives are achieved with growth, it is a model of success in which architecture was a fundamental element,” he says. “But this success has also had a perverse effect, because it has been misinterpreted and attempted to reproduce it without really understanding all the elements that make it up. We sometimes caricature this model, thinking that a simple emblematic or iconic architecture is enough to generate change in a city. And that is a mistake.”