When I read “La Llorería” by Martín Sivak, I couldn’t help but remember his other book, Dad’s Jump, which acts as a correlate to this one and in which the author leaves the intimate testimony of a public event, the suicide of his father, the banker and politician Jorge Sivak.

I still wondered about the way Sivak built the walls of the moral space from which his father threw himself, because these kinds of experiences are inextricably linked to the feeling that the absent person has thrown himself out of life. It is not easy. In “The Place,” Annie Arnaux recalls her father’s life, and when she returns from the city after his funeral by train and with her son, traveling in first class, having climbed the social ladder behind her, she thinks that she has become a bourgeoisie and that it is too late.

After a defeat it is always too late for everything. Perhaps the Llorería begins in the middle of crying, because it begins with an irreversible sentimental break, so much so that the narrator finds as his only support his young son, a curious interlocutor who, despite his age, seems to naturally take over the father’s trance – he does not yet know that an episode of his future sentimental arc is beginning. Furthermore, when he sets off alone on his bicycle without the help of the training wheels, it acts as an act of encouragement for his father, who, however, remains motionless on the wheel of his pain.

Authoritarians don’t like that

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a mainstay of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe that they are the owners of the truth.

The book begins with an initiatory journey through Latin America before falling into a new grief, the death of the mother, a journey with distant echoes of the journey made by Ernesto Guevara on a motorcycle with a similar map, recently graduated from medical school, which was to become a revolutionary future, which in Sivak’s narrative is a small attempt, but which is consolidated in a personal uprising in the company of a Scottish documentary filmmaker.

This adventure between a romantic relationship, appearances of Evo Morales or Hugo Chávez eating coconut sweets to overcome sleep and the approach to Subcomandante Marcos, which the journalists do not reach, is interrupted to witness the death of the mother, which has two consequences. The first is the posthumous encounter with the love letters that Sivak’s parents exchanged before his birth, the reading of which transports him to another dimension of his relationship with them. The other moment is the narrator’s patient observation of his dying mother and, in this trance, the internalization that her body is a detachment from the one he is saying goodbye to. Although both sequences change the narrator, the last one draws the reader along.

This memoir, which seems English for a moment, between revolutionary trials and Islamist purges, has of course had a long passage in London when it is almost over. The narrator, in the trance of a new separation, wanders the city alternately with his partner, the Scottish documentary filmmaker, a survivor of a Taliban kidnapping, defeated and a temporary guest in his mother’s house; a counterpoint to his own life and a new layer of instability on a surface, life that seems to consist of nothing else. At the end there is a reunion scene in Highgate Cemetery before the bust of Marx is placed over his grave (“How nice to see you again, Carlos.”). Surrounded by a small crowd, as his visit coincides with an event next to the mausoleum, he takes photographs and realizes – through Argentine paranoia – that they may take him for granted. He transcribes a fragment of Engels’s obituary on Marx’s death: He was at his house on March 14, 1883, and said he had left him alone for a few minutes and when he returned he found him sleeping forever in his armchair.

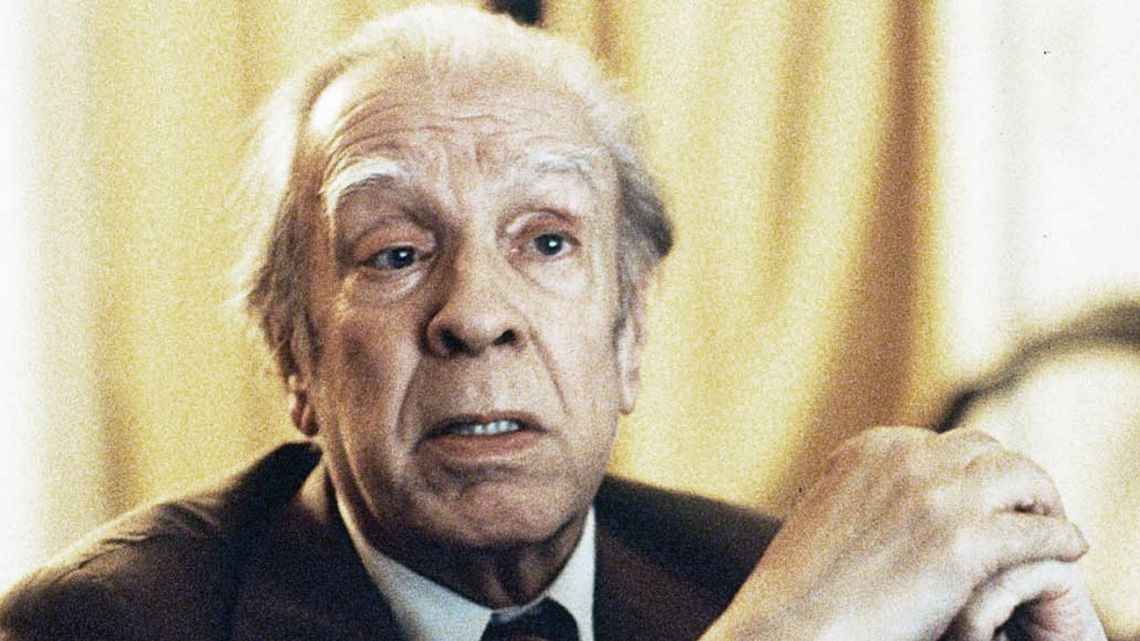

Just two minutes. Only a moment and an eternity open before us. Borges used to say that it was foolish to threaten death during a robbery; What’s scary is eternity. These are losses: eternity that reveals itself in small acts that Martin Sivak lists again and again. The goodbyes and their remnant, which is ourselves, as he understood in the face of his mother’s torment.

*Author and journalist.