It’s barely seven in the afternoon on a warm September evening in the Albufera de Grau Natural Park on the island of Menorca. The few tourists who stay before dark return after taking photos of the idyllic, striped lighthouse. … by Favarich. On their way, they pass around thirty people carrying large backpacks, cameras and tripods, dressed in long pants and jackets which contrast with the almost summer weather. At some point along the way, this motley group leaves the trail to begin walking across country, towards hills where, to the untrained eye, there appears to be nothing. Not for them: these people know that from this precise point, at 8:15 p.m., they will be able to observe (and photograph) a lunar eclipse rising just behind the lighthouse. Clouds permitting, of course.

“My friend and I are from Barcelona,” Juan says, pointing to his partner José, who has a house in Mahón and who invited him those days. “We timed the visit to coincide with the eclipse,” he says as he works to set up the tripod; then adjust the camera and corresponding settings to get the best snapshot. The profile of these two friends is the most common among the participants gathered there and in astrophotography in general: retired with time (and a certain purchasing power); But there are also a couple of friends (“We see more and more women”, both emphasize) and a boy who is not yet thirty, but who has taken a liking to his father, whom he is accompanying this afternoon.

At the same time, other groups like this spread throughout Spain: in Seville or Alcañiz (Teruel), around a hundred gathered in each locality; in Madrid, more than 400 people. Campo de Criptana, Granollers or Santa Cruz de Tenerife also host their own gatherings. Outside our territory, in cities like Lisbon (Portugal), Milan (Italy), Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) or Cape Town (South Africa), there are more people waiting for the eclipse to photograph it. More than 1,200 people in 38 countries attempt to capture the moment when the Earth intersects the light cast by the Sun, creating a shadow that dyes our satellite red, searching for the most spectacular frame aligned with an earthly subject, be it a person, a mountain or, in this case, a lighthouse, realizing the spectacular nature of the moment and the rise of astrophotography.

Some participants in the astrophotography meeting in front of the Favarich lighthouse (Menorca), in the background of the image

Mathematical calculations

Behind these meetings and connecting all these people is PhotoPills, an app created by Spaniards that, almost instantly, provides users with the exact location and time (in addition to the right camera settings) to take the best photo of the sky, whether it’s the Milky Way above a castle in Guadalajara or the winter full moon in New Zealand. Something like a Google Street View of the sky in real time. “Before, you almost had to be a mathematician to find the perfect place and time,” explains Germán Marquès, one of the founders of the company with Rafael Pons, in front of the lighthouse.

Ten years ago, both, tired of their jobs, decided to start a business together. “We started to study the problems that photographers were having at that time, like the time of sunrise and sunset, golden hour, blue hour… We had to do a lot of calculations. For example, if this lighthouse is 28 meters long, what lens should I use to get the image I’m looking for? This is now provided to you by the app.

The Favarich lighthouse with the full moon in the background

Because behind the images of a huge full Moon with a statue in front of it or of a dancer doing a spagat lies a preparation that can take days, weeks or months. “And even years. Imagine you want to photograph an astronomical event that can only be done once a year and that day is cloudy,” explains Jessica Rojas, a professional astrophotographer also present at the Menorca meeting. “It took me up to three years to get a photo.” The PhotoPills algorithm is able to save a lot of time, until now, a mammoth task that was often left to luck and natural expertise, which has encouraged many new fans to try this hobby that is gaining more and more followers.

Spanish astronauts Sara García and Pablo Álvarez photographed in front of the Moon

In search of the best sky

As neither Marquès nor Pons were photographers, they recruited Antoni Cladera, a Mallorcan astrophotographer with a renowned career who is now also one of the guides who travel the world with trips organized by PhotoPills in search of the best skies. He just returned from Namibia and already has another adventure in Canada next week. But today he is present at the meeting in Menorca, the island where he currently resides, accompanying the rest of the group and advising those present. Because PhotoPills is now more than just a tool. “Our intention is to create a community,” says Cladera. This is why the appeal launched via social networks was so successful.

Moreover, he has already placed his camera in front of the lighthouse and is now helping others prepare their photos while laughing. His t-shirt reads “Plan and Pray” (Plan and Pray, in Spanish), alluding to the fact that even though the work of calculating and planning has been done, there is still quite a lot left in the hands of luck. “Ultimately, you depend on the weather,” says Cladera. “If the clouds appear, everything you did before no longer matters. But if luck gives you clear weather…”

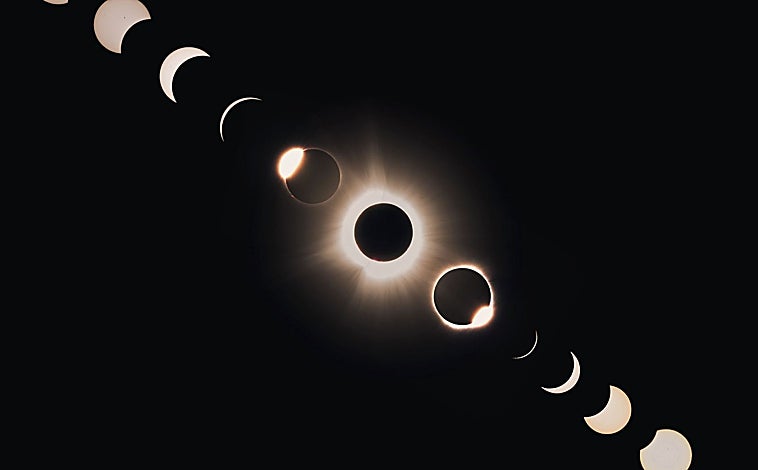

There’s an even bigger challenge than photographing a lunar eclipse: capturing a solar eclipse. This phenomenon occurs when the Moon intervenes between the Earth and the Sun, blocking its light and transforming day into night on a strip of our planet for a few minutes, which will happen precisely here, in our country, on August 12, 2026 and will repeat on the 2nd of the same month in 2027 and on January 26, 2028 (the latter as an angular eclipse). “It’s much more difficult because, if you want to photograph all the phases, you have to do ‘bracketing’ (taking several images of the same scene with different settings) very quickly, in less than a minute at best.”

By changing settings such as exposure, focus or white balance in seconds, and combining multiple images, astrophotographers are able to capture the famous “demon ring” or “diamond ring”, which occurs when the last light of the Sun shines through a valley at the edge of the Moon. Or those known as Baily Pearls, brilliant points of light that appear around the Moon in the moments before and after the solar eclipse caused by the disappearance of light between the lunar mountains. The image of the chromosphere is also very coveted, where we can sometimes capture the eruptions which give rise to solar storms like that of mid-November, which caused the northern lights visible from the south of Spain.

In the main image, all phases of the solar eclipse. On the left, the “Demon Ring”; On the right, the Pearls of Baily, where we can see the last rays of the Sun filtering through the mountains and lunar valleys.

“Beyond the beauty of the images, these photographs have scientific utility,” says Rojas, who learned about it through what she thought was a mistake during one of her captures of a lunar eclipse. At first, he believed that this bluish band which appeared between the shadow and the satellite was a defect in the photograph; But when he investigated, he discovered that it was our planet’s ozone layer. “It’s a real-time reflection that is very difficult to capture and that scientists use to know very reliably what that protective layer is at that moment,” he says. The same thing happens with solar eclipses: they are an effective way to study the solar corona, which normally cannot be observed because the brightness of our star “eclipses” its details.

Spain, lucky country

It is for this reason that the next three solar eclipses that will be visible from Spain will bring together not only curious people and astronomy enthusiasts, but also scientists from all over the world who, using Spain as a base of operations, will extract all kinds of information from the Sun and the Moon. And, of course, the astrophotographers who will be even more incentivized: “The Sun will hide behind the still eclipsed horizon, which will give us a unique opportunity to align it with anything,” explains Rojas. “Eclipses usually take place at the zenith (the highest point in the Sun’s sky), which is why we’ve traditionally seen people jumping out of small planes or doing crazy things to take a photo. In Spain next year we will be able to do it on the horizon, without breaking a sweat.

“I have already booked accommodation for August next year in a town near Gijón,” explains Juan. “Let’s see if we’re luckier than today,” he said as he collected his things at night after only being able to capture an overcast sky. In the PhotoPills chat, photographers from other parts of the world experienced the same fate: a cloud eclipse. Soon after, Rojas and Cladera also began storing material in light of the front ends.

One last look changes the plan. “Wait! Do you see that? The four or five brave people still there look through their cameras. “Yes, we can still see the bite!” Above the Favarich lighthouse the sky opened and the yellow circle of the full Moon shines for a moment, revealing a gap. In the end, Juan was right: we had to maintain hope.