There’s an interview with Paul Thomas Anderson, from when the guy was a kid and had just made “Magnolia,” in which he interestingly justifies the length of the film, three hours and eight minutes.

Until then, three-hour films were reserved for war films or those that dealt with serious social issues. But for the director, the daily lives of ordinary individuals have always expressed something great. All it took was eyes to see and the courage to look in the right place.

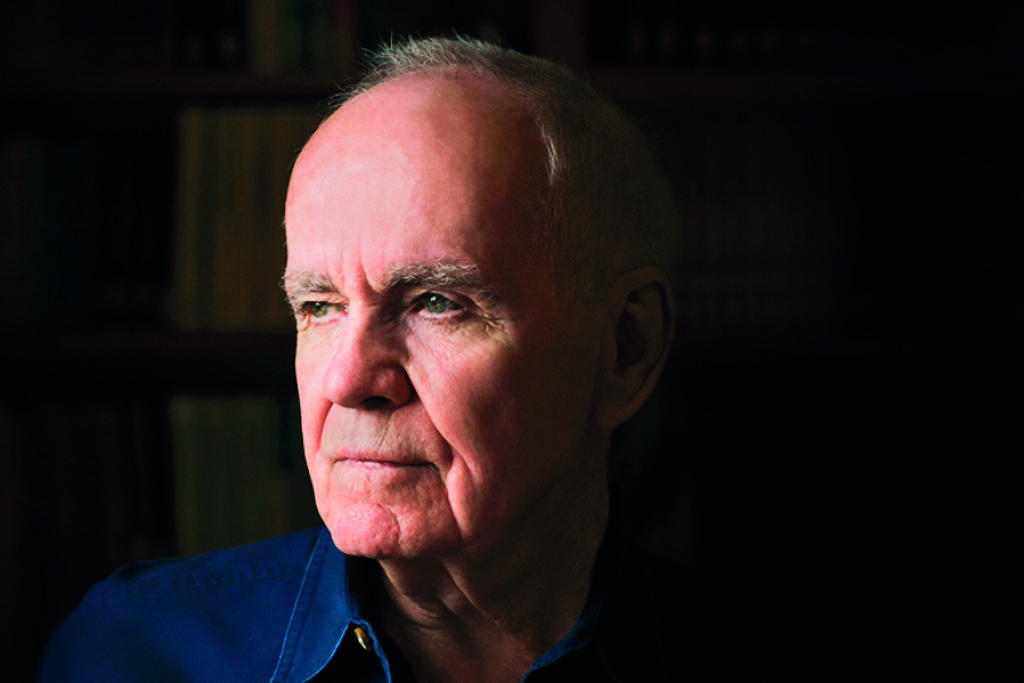

It is in this spirit that Cormac McCarthy wrote “Suttree”, his fourth book, a novel of almost 600 pages, published in the United States in 1979 and which arrived for the first time in Brazil, by Alfaguara.

The story is simple. Cornelius Suttree separates from his wealthy family because he decides to live as a fisherman in the town of Knoxville, alongside drunkards and other unfortunates.

“Suttree” is often compared to James Joyce’s “Ulysses”. McCarthy would have done in Knoxville what the Irishman did in Dublin. In both books there is a plurality of voices and a mixture of colloquialism, vulgarity, scholarship and mythology. In both novels, fart jokes and scholastic philosophy coexist.

During his trip, Cornelius Suttree meets Gene Harrogate, a simple-minded guy, an inveterate crook, but pure of heart, in the way that a guy who sleeps with watermelons can be pure of heart. Amidst the desolation of Knoxville, the two become friends.

While the former, with a thoughtful and introverted temperament, develops an older brother relationship with the latter, Harrogate is the comic relief in the dark environment created by McCarthy.

Their friendship is a more “key in the chain,” but no less awkward and fun, version of the partnership of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, or Caesar and Olavo in “Vale Tudo.”

McCarthy’s literary world is cruel and opaque. There is no God, or if He exists, it is not the merciful version of the New Testament, but the vengeful and violent version of the Old.

However, “Suttree” stands out in his work: there is an almost picaresque humor and the characters are treated with tenderness and compassionate humanism.

The protagonist’s trajectory is, in form and theme, a tale of asceticism. It turns out that “Suttree” is no saint. On the contrary, he is a sinner, I admit that he embraces the world as it is: profane and imperfect. His journey is a secularized way of the cross. There is sacrificial suffering, even if redemption never comes.

McCarthy uses his language full of linguistic anachronisms and biblical grandiloquence to recount ordinary events. His prose gives an existential grandeur to what, in other hands, would be a succession of daily banalities.

Daniel Galera’s translation is precious: the archaisms and polysyndetons, the elaborate syntaxes, in short, all the aesthetic sensation of the original diction is present.

James Wood, critic of the New Yorker, reminded us that excessive pomp is a risky game. When McCarthy gets it right, it’s great. But when you get it wrong, it feels like a stilted theatrical pastiche. As the critic says: “The problem is not the melodrama, but the imprecision and sometimes even the absurdity.”

Consider, for example, this description of an orgasm scene in “Suttree”: “(…) and how his eyes rolled back like those of a Turkish beggar, leaving only the brilliant blue-white beneath his half-open lids (…).” If there had already been a Bad Sex in Fiction Award in 1979, “Suttree” would have competed for the gold medal.

McCarthy is the bastard son of Flannery O’Connor. Less for the style, more for the thematic universe and Catholic metaphysics. Although he declared himself an agnostic, his upbringing was Catholic and Apostolic. Additionally, both were affiliated with the Southern Gothic literary tradition.

O’Connor’s statement about the American South is well known: “It’s easier to find an angel walking down the sidewalk than an insurance agent.” » In Cornelius Suttree’s dilapidated and enchanted Knoxville, it’s not so different.