Ancient chronicles are full of monarchs whose traces have been almost erased by time. Nabonidus of Babylon lost his throne by retreating into the desert to honor a lunar god; Amenmesse disputed power with his own family in the Egypt of the Ramses; or Mithridates II, who extended the Parthian domains to the Caucasus, barely occupies a line in the textbooks.

The list is long and shows how many sovereigns, despite their influence on events, barely retain a place in memory. The recent appearance of the name Artaksiade on an Aramaic stone from Anatolia is part of this same category of figures which reappear centuries later, prompted by a chance discovery which saves them from oblivion.

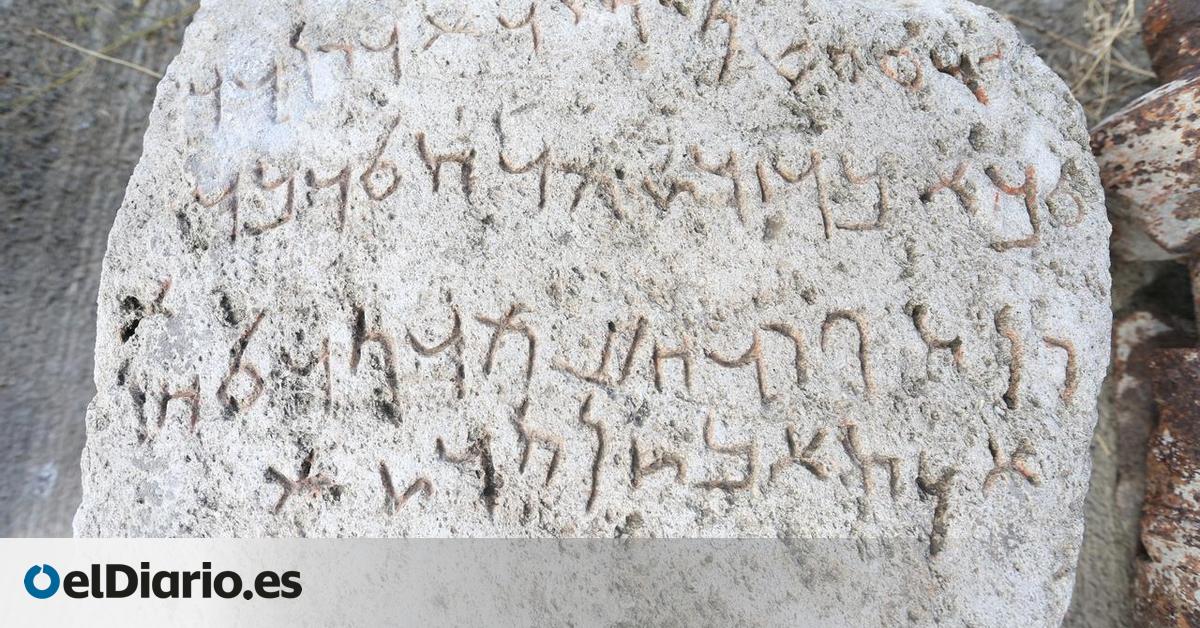

Specialists attempt to decipher a text deteriorated over the centuries

A stone with inscriptions found in the Turkish province of Ardahan revealed, for the first time in the region, the presence of a Aramaic text engraved on its surface. The piece, transferred to the Kars Museum of Archeology and Ethnography, aroused enormous interest among specialists because contains the name of Artaksiadidentified as a monarch of the Seleucid period. The experts always They debate which king with this title the inscription refers to, even though the most accepted hypothesis suggests that it is the first known Artaksiadkey figure in the transition between Greek domination and Roman consolidation in eastern Anatolia.

Epigraphers now strive to decipher the signs of the text, deteriorated by the passage of centuries. The objective is get a full reading this helps to understand the actual content of the inscription. The preserved parts show Aramaic characters incised with remarkable skill on an irregular rectangular base. Researchers reconstruct word fragments from barely perceptible features, which requires a in-depth process of comparison with epigraphic directories and cross-references other regions of the Middle East. When they have completed the transcription, a translation is planned which specify whether the message was a dedication, a political proclamation or an administrative document.

The museum suggests that the stone could have served as border marker. In ancient times it was common to use engraved inscriptions to indicate the borders between territories or communities. In the neighboring province of Iğdır Aramaic texts serving this function had already been located, strengthening the possibility that this new discovery served the same purpose. If the name Artaksiad is linked to this usage, the inscription could reflect a reaffirmation of royal power over a contested territory, a common practice in times of reorganization after defeats or dynastic changes.

Museum officials, led by Hakim Aslanhighlight the exceptional nature of the discovery. Aslan explained that this is the first Aramaic text documented in the Kars and Ardahan region, which changes the linguistic map of Eastern Anatolia. Aramaic, an administrative language in large areas of the Near East, had been considered marginal in these provinces, but its presence demonstrates that it had a broader function, perhaps linked to diplomacy or commerce. The detailed analysis of the characters will make it possible to clarify the chronology and establish links with other centers of power of the time.

Artaxias I appears as the figure who gives meaning to the discovery

Artaksiad’s name probably refers, if the main theories are true, to Artaxias I, Founder of the Artaxid dynasty in Armenia and former satrap under Antiochus III. After the defeat of the Seleucid monarch against Rome in 190 BC, Artaxias obtains the support of the Roman Senate and proclaims his independence. He consolidated his authority through campaigns in the Iberian Peninsula and Media Atropatene, extending the Armenian borders to the Kurá River. founded the capital Artachat around 185 BC, planned according to Hellenistic urban guidelines and carried out maintain sovereignty in the face of pressure from Antiocho IV. Their dynasty lasted until the 1st century, marking a long period of regional stability.

The importance of Artaxias I lies in its ability to transform a fragmented territory into a unified and recognizable kingdomlocated between the Roman, Parthian and Seleucid empires. His policy combined the adoption of Greek administrative models with an affirmation of local identity which consolidated the Armenian monarchy. The discovery of Ardahan thus offers a possible direct reference to his figure, which broadens the geographical scope of his influence and suggests the existence of more extensive networks of communication and control than previously thought.

The discovery therefore not only provides a new epigraphic document, but also opens avenues for study on the circulation of languages, the legitimacy of power and contacts between kingdoms in a little-explored region. Map of Kars archaeologists include the stone in the museum’s permanent collection once the restoration is complete. Each deciphered fragment makes it possible to reconstruct a political map which, two millennia later, still conceals secrets about the way in which ancient kings attempted to record their passage through history.