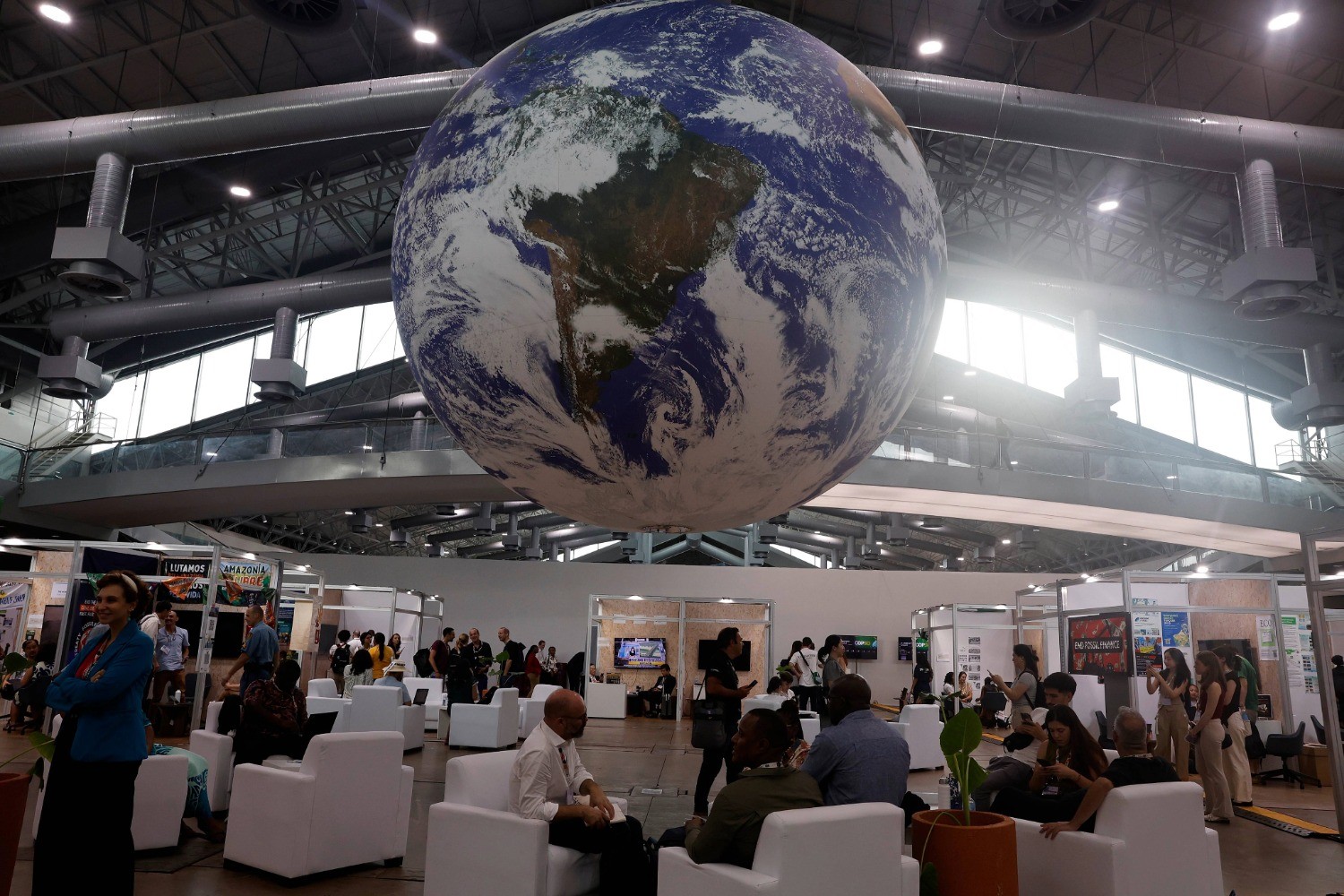

After 13 days of negotiations in the capital of Pará, the 30th United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP30) concluded on November 22 with the approval, by 195 countries, of the Belém Package. Although sparking frustration over the lack of mention of fossil fuels, the documents show progress on the climate justice agenda, with unprecedented mentions of people of African descent. The references appear in four texts: Just Transition, Gender Equality Action Plan, Global Adaptation Goal and Mutirão (the set of most relevant decisions of the conference).

For the director of the Ford Foundation in Brazil, Átila Roque, from the point of view of the black population, COP30 was an important step and a great victory. “The key conference documents recognize that the climate crisis has an unequal impact on people of African descent, that they must have a voice in this process and that they are a central part of the solution,” he says. The Ford Foundation participated in the Belém conference with a pavilion dedicated to climate justice.

Roque highlights the unprecedented alliance between indigenous peoples, quilombolas and traditional communities, who launched the campaign in 2024 “The answer is us” claim the main role in decision-making spaces. The mobilization strengthened demands and argued that there is no climate justice without territorial, social and popular justice.

The climate crisis, according to Roque, is not strictly ecological, but also a social justice agenda, whose solutions must be integrated into development and equality policies. “We must move forward and recognize equity as a climate agenda. In a country like Brazil, social justice is necessarily a racial equality agenda,” he emphasizes.

Geledés – Instituto da Mulher Negra is one of the organizations operating since the Rio-92 Conference with the aim of placing race-related issues at the center of climate governance. In a press release, the organization considers that the inclusion of people of African descent in the official texts of COP30 constituted an important step forward in international climate policy, built over decades.

“In 30 COP (climate conferences), we had never managed to recognize the existence of people of African descent, their vulnerabilities in the face of the climate crisis and the central role that these populations play in climate resilience,” underlines Thaynah Gutierrez, climate and environmental racism advisor at Geledés.

In practice, explains Gutierrez, the mention in official documents makes it possible to advance priority public policies in favor of people of African descent. “Recognition in itself does not fully guarantee the policies, institutional capacities and resources necessary to effectively combat environmental racism and protect people of African descent,” he emphasizes. She adds that next steps require integrating these decisions into national public policies and expanding spaces within the UNFCCC to discuss the needs and vulnerabilities to which these populations around the world are subject.

The International Coalition of Territories and Peoples of African Descent in Latin America and the Caribbean (Citafro) also celebrated this mention in the official COP30 documents. However, he criticized the fact that the quote referred to “peoples” and not “peoples” of African descent. In the opinion of the organization, this fact reinforces structural racism and deprives millions of people of rights who self-determine and recognize themselves as ethnic people.

“We appeal to the UN and the governments of the world: it is time to move towards the full participation of people of African descent in the international environmental system, with the recognition of our collective rights and the attribution of title to our lands,” says José Luis Rengifo, representative of Citafro.

Rengifo considers Colombia’s proposal to promote an international declaration and create specific financial and legal instruments as an indispensable step to settle a historic debt. According to him, it is not possible to continue talking about climate solutions while marginalizing those who risk their lives to defend nature. “Colonialism, slavery and structural racism are at the root of the climate crisis; therefore, without racial and territorial justice, there will be no real and lasting solutions for the planet,” he emphasizes.

The National Coordination of Articulation of Black Rural Quilombola Communities (Conaq), which represents the quilombola population in Brazil and is also part of Citafro, considers the mention of Afro-descendants as a historical recognition. For the organization, this progress is collective and reflects the strength of the quilombola communities, women, young people and all those who continue to defend the territory, life and justice. Conaq also highlights that this was an important step for global policies to finally take into account the knowledge, vulnerabilities and, above all, the role of Afro-descendants “in building a more just and sustainable future, without racism”.