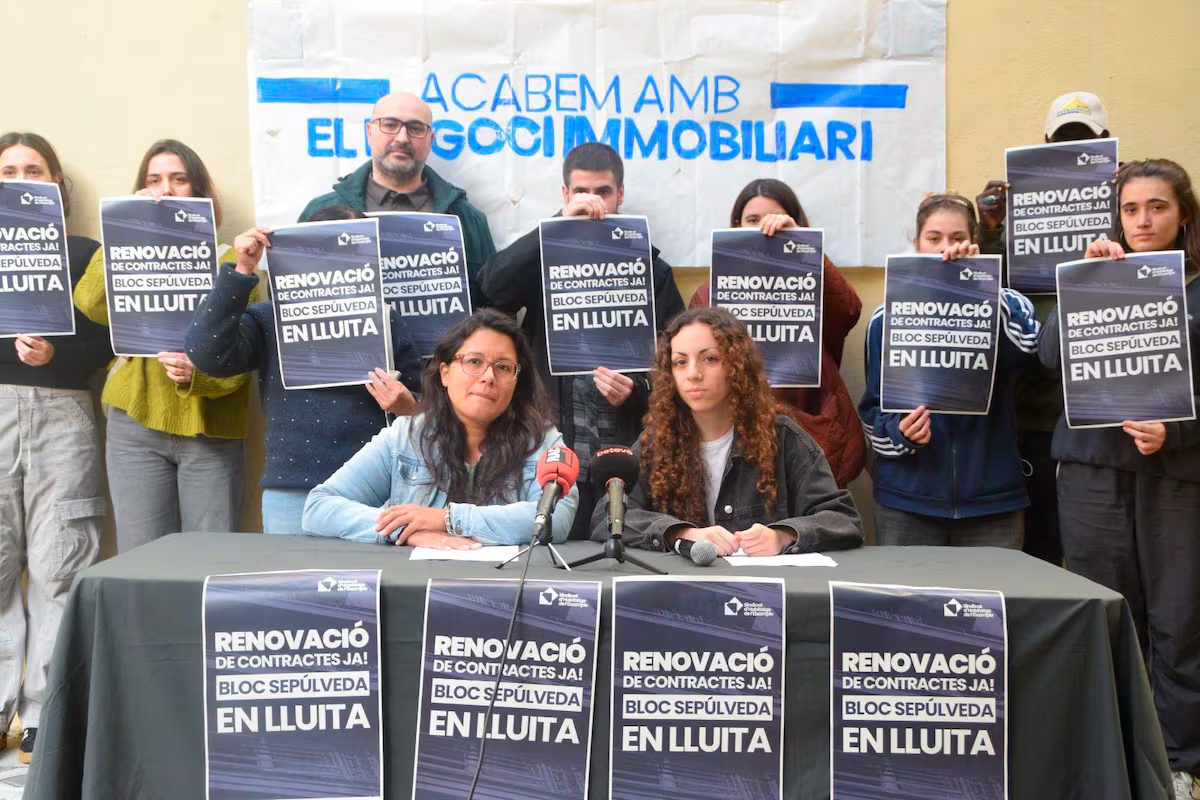

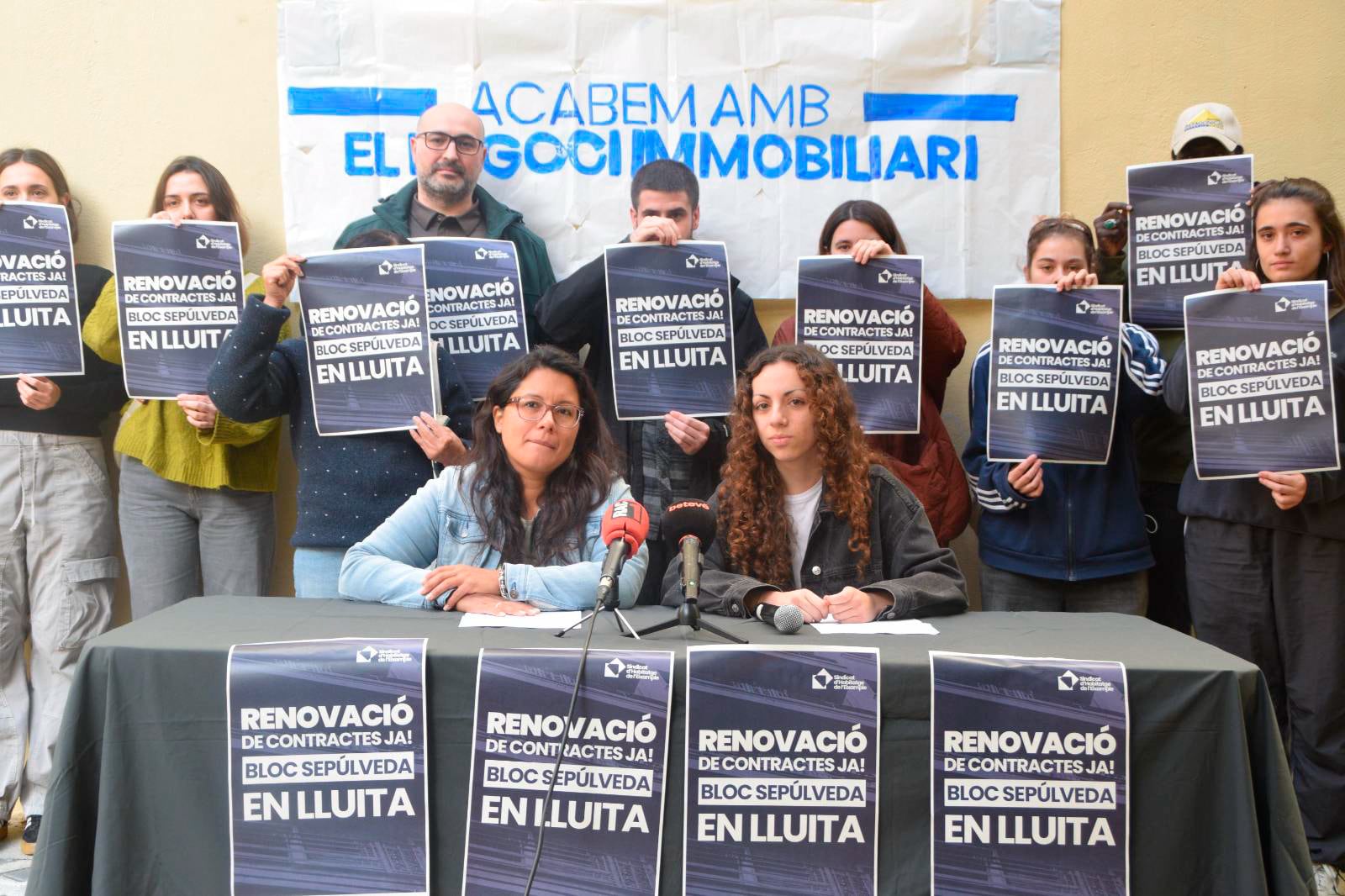

The city of Barcelona opened a new building with tenants threatened with eviction from its floors: as happened on this day in Casa Úrsula, the neighbors of No. 83 on Sepulveda Street, in the Sant Antoni (Eixample) neighborhood, were presented as a “bloc to fight”. They explained from the region’s Sindicato Socialista de Vivienda that last June, the heirs to the farm property were sold to a company and they sometimes began receiving calls warning that contracts would not be renewed upon their expiration. The new property is Fandor, “a real estate investment, promotion and management company based in Barcelona, and focused on the non-permanent housing sector,” according to its website.

Like many other buildings in the Eixample and in other neighborhoods of the city, such as Gràcia or Poble Sec, it is a building in which elderly people, families with minor children, and some single parents, have lived since their birth. Among the 28 floors of the Finca, there are new spaces. Elsewhere, he lives with the Sword of Damocles before his contracts expire. The ones that will end more quickly are one in December and another starting in 2026. Erika, one of the women, mentioned in the press that there were people in a vulnerable situation on the farm and stated: “Little by little, they walked in front of them, who wanted to avoid conflict, or because they thought they had nothing to do in the face of this situation.” In the case of the new building discovered by their neighbors, the vacant homes are still not under construction and remain boarded up.

“Sepulveda 83 is a prime example of how the real estate sector is forcing people out of their homes: large tenants and investment funds are buying up existing buildings and making a profit through the practice of splitting floors in housing, seasonal rentals and real estate. Coexistence“At the expense of the home as a fundamental right,” the union members insisted, citing the case of the Babalona block on Lanka Street, a few hundred meters from Sepúlveda, 83.

The union and organizing leaders confirmed that they tried to contact Fandor, “but there was no response.” By learning about their situation, they seek pressure to begin “negotiations” with their new home and “stop the building being vacant.” Among those affected was also Boris Ohlert, who told Petitvi that the contract would expire in a few months, and expressed his fear for the future: “My children are learning in the neighborhood, and here we have our support network and we could not stop at Sant Antoni in the neighborhood elsewhere, because of the high rental prices.”

In February this year, the Eixample animal associations updated data from a study conducted by the Federación de Asociaciones Vecinales (FAVB), the five associations in the region (Dreta, Esquerra, Nova Esquerra, Sagrada Familia, and Fort Pienc) and the Sindicato de Inquilinas. They alerted that there are 232 properties in the area bought or managed by companies, about 70% of the rentals are seasonal (if you look on internet portals), about 21% of the beds in the area are offered to tourists, and since 2016 there have been 4,000 invisible vacancies (in which they did not walk in previous years of their own free will, which is a sin because it could not face the conditions imposed on new cases). The associations have 10,000 residents evicted by these invisible losses (hitting the buildings at an average of 17 floors per property and 2.5 people per floor, and in a scenario where 100% of residents are evicted).