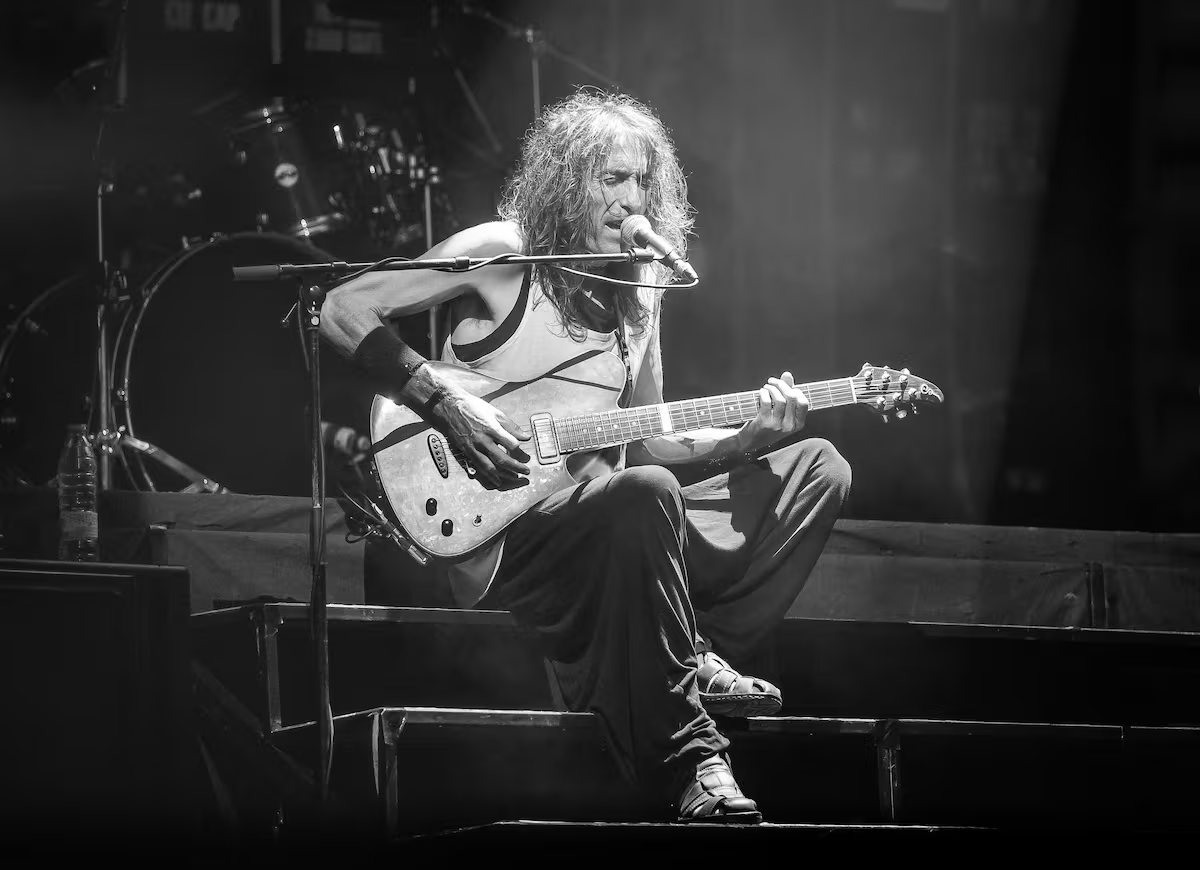

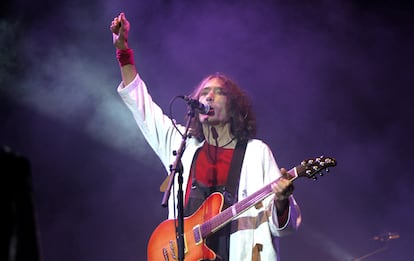

From today there may be millions of tributes to Robe Iniesta and Extremoduro, but Robe Iniesta, who died today at the age of 63, there has been and will only be one. Because he was a musician who, unclassifiable in his anger and his tenderness like two sides of the same mirror with their impressive brilliance, emerges every three or four generations, perhaps every century, like the poets of the soul, the misunderstood geniuses or the great lucid madmen, those who open a gap between the lines of societies, who go beyond the margins of everyday life to teach the value of the human, or, as in the case of Robe, sing it from the heart in the throat, the soul in the air, with hosts against the elements and as if trying to impose light in hell.

“Nothing is unthinkable, nothing is impossible while this song plays,” Robe sang in The power of art, theme from his latest album, The air carries us away, published in 2023. Today, on a day as sad as that of Robe’s death – and impossible to assimilate after yesterday’s death of another giant like Jorge Martínez – it almost seems like an ominous testimony to what the figure of Robe Iniesta means for Spanish culture, an unwitting artist, a transgenerational musician, a philosopher of the streets, a voice that sang for ordinary people because they were ordinary people since he made his name on the Spanish music scene with Extremoduro, at the end of the eighties, when in the multi-colored Spain of the scene, a group from Plasencia, like the one he led, with so much desire to break sets, put your finger on the sensitive spot and touch your nose, was the closest thing to the Sex Pistols that you could see in the land of ham and wineskins. The Spanish Sex Pistols could have been a good label, but it wasn’t necessary: they were Extremoduro and they put a lot of emphasis on labels and promotional campaigns. Extremoduro or the great trench rock of Spain which owes everything to Leño and Rosendo.

And, while trenches have always existed, for many, there was never one like the one symbolized by Extremoduro. The first of the trenches to go on the charge, whether at night or early in the morning, in the neighborhood or in town, in groups or in groups. Whether with nothing to lose or with everything lost. Whether with or without the battlefield. And always when desire surpasses all logic.

Extremoduro stood out from the others with a powerful and unbreakable personality, combining hard rock and sharp existential lyrics. They were their own voice. With a first album like transgressive rock, published in 1989, they went for the jugular. The tear moved songs like The bonfire, Jesus Christ García, You’re going to break And Sandwich. “I feed the black vultures with my meat,” Robe sang angrily in Estremaydure. The black vultures, the same ones that populated their lands of origin. Extremoduro came out of nowhere, literally, because they came from the wastelands of Extremadura, land of radioactive acorns and created by God on the day he “hadn’t giñado”, where trains from Madrid take longer to arrive than planes to New York. The world of Extremoduro was a world of marginalization. It was a dream, but in a nightmare atmosphere. An addictive nightmare because it is revolutionary, not at all complacent, highlighting all the vital delusions so typical of adolescents, these beings who feel more marginalized than others and at the same time the most important in the world. The members of Extremoduro called it “transgressive rock”. They were proud of a label that also differentiated them from others, including all those groups like Los Suaves, Barricada, Platero y tú or Reincidentes, with whom they maintained links of subversive cries and street philosophy. A real sword against the snobbists that, years later, without Extremoduro, Robe Iniesta himself would continue to brandish as a lone rider throughout the 21st century.

The world of Robe Iniesta is now associated with the irrational philosophy of Nietzsche. Beyond the similarities in thought between this universal philosopher and his collection of songs, it was enough to chat with Robe, a racial and self-taught lyricist and at the same time elusive character, to know that his thing was more to hang out at home. It had more to do with Henry Miller and Charles Bukowski, notably in this use of the slum and free language populated by cocks, sperm, panties, stripes and wafers, but even more with the poets he cites in his compositions such as Antonio Machado, Miguel Hernández, Federico García Lorca, Pablo Neruda and the novelist Benito Pérez Galdós. In this way, if it were ever concluded that Nietzsche would listen to Extremoduro, then it could be argued that Miguel Hernández would sing Extremoduro’s songs. Maybe the same poet who wrote his poem would shout them out Sitting on the dead: “I am here to live / as long as my soul rings.”

The soul resonated in the bastard songs of Robe Iniesta, for whom Camarón was as important as Frank Zappa. Jean-Paul Sartre said that “all emotion is a transformation of the world”. Robe knew it. Robe sang it. Robe seemed to be risking her life on this. Robe went further than many because he sang at the very heart of an emotion which was not born from a vocation of social distinction and cultural elitism, like that of so many artistic scouts who have populated and still populate trend magazines and cultural programs. Because Robe was an absolute minority, the philosopher of the streets of the great trench, the very one who today more than ever will be honored in the media and even in the soup, even if his great tribute was paid during his lifetime for decades in the orchestras of all the cities of Spain. Because this is Robe Iniesta’s great triumph: being the most covered poet at festivals. It is his homeland, as his homeland is his music, the anger of human love in the face of a world that seems even more irrational than it already was when he rose to prominence, triumphed, and became almost a legend in life.

“I want to hear a song that doesn’t talk nonsense and says that love isn’t enough,” he sang in The sidewalk in front of the back door. And much more, Robe. Yet, always. Or, as he said in It happens, a song that helps “clarity enter the ruin”. In a world in ruins like ours, his voice will not disappear. It cannot and should not. When I first interviewed him a few years ago, Robe was sitting in front of me, covered in a granny blanket and a cup of tea, and he said to me: “In 50 or 100 years there will be people wondering who those guys were who left it like fucking garbage. What bastards, what scum.” These guys were all of us.

But there is always the possibility of the power of art. while he sang Nothing to lose, from his latest album: “I’ll ask the heart that it must go / They’ll tear it away from me… I’ll look for wrongs to undo / And battles to fight that were lost / I’ll look for things that are impossible to achieve and don’t mind failing / And try again.” And, as if it were the best sword we have left to fight nonsense and lack of humanity, nothing is unthinkable, nothing is impossible, as long as the songs of Robe Iniesta resonate.