In the 1990s, a few years after the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant on April 26, 1986, a group of scientists led by microbiologist Nelli Zhdanova of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine embarked on a field study. … Their goal was to find out if there was life in the exclusion zone, a place that extends 30 kilometers around the facility, and, if so, what kind. Hopes were not high: the effects of radiation were still being felt among those nicknamed “liquidators”, those who helped with the clean-up work and who continued to die of cancer even years after participating in the work.

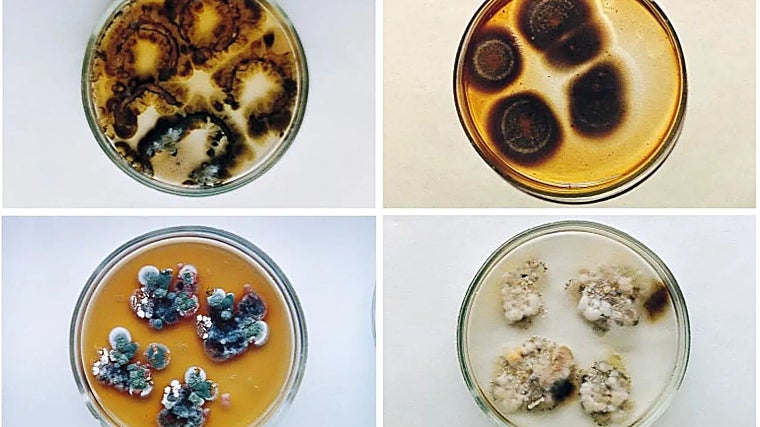

The surprise was great when they detected that an entire community of fungi comprising up to 37 different species was proliferating around the reactor. They all had something in common: most of them had a dark, even black tone. And among them, Cladosporium sphaerospermum stands out, a fungus that dominated all the samples and which subsequently became the protagonist of many subsequent studies and even a trip to space.

The secret of these beings, according to the study published by Zhdanova’s team in the journal “Mycological Research”, was none other than the melanina substance found in most organisms (including ourselves) that protects against ultraviolet rays in exchange for darker skin coloring. And that’s not all: according to the team, these fungi could take advantage of radiation to proliferate and even generate energy to survive in this hostile environment. However, today, forty years after the discovery of these strange “radioactivity” mushrooms, the functioning of this “superpower” still remains unknown. If it exists.

A controversial theory

“I have doubts about how this mechanism works,” Germán Orizaola, professor of zoology at the University of Oviedo and expert on the effects of radiation on animals, told ABC. “Several groups have done extensive research on the topic and, as of yet, the specific system they are intended to use has not been identified.” Orizaola refers, for example, to the study carried out by Ekaterina Dadachova and Arturo Casadevall, from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (United States). They discovered that ionizing radiation does not harm the fungus as it would other organisms. Plus, as they pointed out, it grew when “bathed” in it.

Melanin, a pigment that gives skin color, protects the body against ultraviolet rays

A few years later, in another work published in 2008, they proposed the theory that this fungus and others like it could collect radiation to convert it into energy (radiosynthesis), much like what chlorophyll in plants does with light. However, they also failed to find the exact mechanism supposed to produce all this energy.

“The debate comes because if melanin protects against radiation, which is proven, it is logical to think that beings that produce more will proliferate more easily in these environments; but that doesn’t mean they benefit one way or another,” says Orizaola. Because despite Dadachova and Casadevall’s study, other similar work has not found the same trend: Zhdanova herself and her colleagues published another study in 2006 in which they described that only 9 of the 47 species of melanized fungi they collected in Chernobyl grew into a source of radioactive cesium.

And in 2022, researchers at Sandia National Laboratory in New Mexico found no difference in the growth of two fungi — one melanized and one not — to ultraviolet light and cesium-137.

Survive in space

The power of melanin has been contested beyond Chernobyl and laboratories. An experiment described in an article published in the journal “Frontiers in Microbiology” in 2022 took C. sphaerospermum, the famous fungus that grows in nuclear power plants, to the International Space Station (ISS), where it was allowed to grow outside the orbiting laboratory, exposing it to the full impact of cosmic radiation.

The purpose of this article was not to demonstrate or study radiosynthesis, but rather to explore the fungus’ potential as a radiation shield for space missions. “If this were demonstrated, these organisms could be used to cover lunar colonies, for example, and have a cheap layer of protection against radiation,” says Orizaola.

Cultures found in the fourth unit of Chernobyl, including Cladosporium sphaerospermum. The upper right plate clearly shows melanization

However, until now, scientists have not been able to demonstrate ionizing radiation-dependent carbon fixation, metabolic gain from ionizing radiation, or a defined energy harvesting pathway. “Actual radiosynthesis remains to be demonstrated, and we are far from proving the reduction of carbon compounds to higher energy forms or the fixation of inorganic carbon driven by ionizing radiation,” writes the team that led the study.

“It is very likely that in the experiments in which positive evidence of possible radiosynthesis was observed, other mechanisms are involved,” explains Orizaola, who also visited Chernobyl several times precisely to study how life proliferates in a place a priori as hostile as the exclusion zone.

Brown frogs in Chernobyl

In fact, Orizaola’s team witnessed the power of melanin in animals in the exclusion zone. While walking in the forest, they found specimens of Hyla orientalis, frogs very common in the Caucasus region, extending towards western Asia. However, this amphibian, which is normally bright green, had a dark color in Chernobyl, even black in some specimens. The surprise came when, when analyzing these “brown” frogs, they did not find radiation levels higher than normal.

Chernobyl’s brown frogs showed no higher radiation levels or any signs that the nuclear environment was affecting their health.

“They survived because they were darker, but the accident did not cause any genetic changes in them,” Orizaola explains. That is to say, the darkest and, therefore, the most protected by melanin, were those who resisted the catastrophe which, at the beginning, as was the case with the liquidators, affected life; and, in turn, these tougher brown frogs reproduced and gave rise to greater numbers of darker frogs. “But it is not the radiation which directly caused this color,” specifies the researcher.

On the right, a common tree frog; On the left, a frog of the same species found in Chernobyl

Although the team has not been able to visit the exclusion zone since the war in Ukraine, using information and samples collected at Chernobyl during previous fieldwork, they were able to continue their research into the effects of radiation on these curious frogs. In a study published in the journal “Biology letter”, Orizaola’s team emphasizes that “no effect of absorbed radiation on the age of the frog nor on the length of telomeres (biomarker of cellular aging and biological age) nor on the levels of corticosterone (stress hormone) was observed”. In other words, the radiation had no impact on the life and health of these frogs.

“Super-powered” mushrooms aside, what is clear is that, despite the radioactive catastrophe that marked Chernobyl, today, more than three decades later, the exclusion zone has transformed into an unexpected garden. Life, in its most resistant and surprising forms, has found its space in this apparently cursed territory. But this recovery also invites us to reflect on the real threat weighing on our planet: human activity.