image source, Hulton Archive via Getty Images

-

- Author, Laura Gozzi

- Author title, BBC World Service

“Every moment of that abortion was a surprise to me,” remembers Annie Ernaux.

The French writer, now a Nobel Prize winner for literature, talks about the secret operation that almost cost her her life in 1963.

She was 23 years old, studying at university and dreaming of becoming an author.

She was also the first in a family of workers and small business owners to gain access to higher education, an achievement she said was crumbling before her eyes.

“Sex had finally taken its toll on me, and I saw what was growing inside me as a sign of my social failure,” he later wrote.

In her diary from this time, the single-word entries she wrote while waiting for her period read like a countdown to doom: LAUGHTER. NOTHING.

The options were to induce an abortion herself or find a doctor or someone to help her have a clandestine abortion in exchange for money.

The latter option generally applied to women known as “angel makers.”

However, it was almost impossible to obtain information about it. Abortions were illegal and anyone who took part – including the pregnant woman – could end up in prison.

“It was a secret. Nobody talked about it,” Ernaux remembers.

“We girls back then didn’t know anything about how an abortion was performed.”

A work that is part of the French school program

Ernaux remembers feeling abandoned but also determined.

By writing about this time, I wanted to show the enormous strength it took to overcome such a problem alone.

“It really was a fight to the death,” he says.

Ernaux recounts these events in his work using sober and direct language, without looking away.The event“.

“It’s the detail that counts,” he says.

“The detail of the knitting needle I took from my parents’ house. Or not knowing that I would also end up having to remove the placenta.”

She ended up bleeding to death in the hospital and was quickly evicted from her university dormitory.

“It’s the worst kind of violence that can be inflicted on a woman. How can we allow so many women to go through this?” she asks.

“I wasn’t ashamed to tell it. I was motivated by the feeling that I was doing something historically important.”

Over time, she realized that the silence that had surrounded clandestine abortions for so many years had extended to legal abortions as well.

“I said to myself: All of this will be forgotten in the end.”

Published in 2000, “The Event” is now part of the school curriculum in France and has been made into a multi-award winning film.

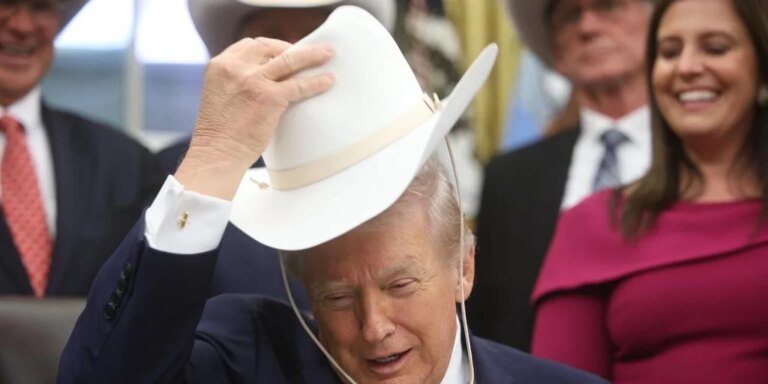

image source, Getty Images

Between 300,000 and a million women

Ernaux believes it is vital that young people know the dangers of clandestine abortion, especially because politicians sometimes try to limit access to legal abortion.

He refers to current cases in some US states and Poland.

“It is an essential freedom to be able to control your own body and therefore reproduction,” he says.

France recently enshrined the right to safe abortion in its constitution, becoming the first country in the world to do so.

But Ernaux insists that the countless women who died from illegal abortions also be recognized.

Nobody knows how many there were; The cause of death usually remained hidden.

It is estimated that between 300,000 and a million women had clandestine abortions each year in France before legalization in 1975.

“I think they deserve a monument like the one they built for the Unknown Soldier in France,” he says.

Earlier this year, Ernaux was part of a delegation that proposed such a monument to Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo.

Whether or not progress is made depends, he admits, on the outcome of the March elections.

The issue remains deeply troubling.

At theater performances of “The Years,” an adaptation of her book that includes an abortion scene, it is not uncommon for some audience members to leave the theater.

It has also received unexpected reactions.

“I was born in 1964, this could have happened to me!” a university professor told him.

“It reveals the extraordinary fear that exists of the power that women can have,” she reflects.

In his work, Ernaux examines his own life without hesitation. Her books are about painful experiences that many know but few dare to name: sexual assault, family secrets, the loss of her mother to Alzheimer’s.

“These things happened to me so that I could tell them,” he writes at the end of “The Event.”

However, the author refuses to impose current values on the past: her goal is to reconstruct exactly what she experienced at that moment and how she felt.

In “A Girl’s Story” she tells of her first sexual experience: She worked at a summer camp and was abused by an older camp director.

At that moment he didn’t understand what was happening to him; He felt “like a mouse faced with a snake and not knowing what to do.”

Today he recognizes that this would be considered rape, but explains that this word does not appear in his book. “Because for me the essence is to describe exactly what happened without passing judgment.”

image source, Gamma Rapho via Getty Images

These events were recorded in Ernaux’s personal diaries, which he began writing at the age of 16.

After her marriage, she kept these precious memories, along with letters from her friends, in a box in her mother’s attic.

But when her mother moved in with her and her family in 1970, she brought everything in the attic with her… except that box and its contents.

“I realized that my mother had read them and decided to destroy these letters and memories,” Ernaux recalls. “She must have been completely horrified.”

The loss was enormous, but Ernaux didn’t want to ruin their relationship with a useless argument. And somehow her mother’s attempt to erase the past failed.

“The truth survived the fire,” Ernaux writes in “A Girl’s Story.”

He claims that without his diaries he had to rely on his memory, which proved sufficient.

“I can go through my past whenever I want. It’s like showing a movie,” he explains.

In this way he also wrote his influential work “The Years”, a collective history of the post-war generation.

“I just had to ask myself: What was life like after the war? And I could imagine it and hear it,” he says.

These memories belong not only to you, but also to the people you shared your story with.

Ernaux grew up in her parents’ café in Normandy, northern France, surrounded by customers from morning to night.

As a result, he learned about adult problems at a young age, which sometimes embarrassed him.

“I wasn’t sure if my classmates knew as much about the world as I did,” she says. “I hated hearing about drunk men who drank too much. Many of these things embarrassed me.”

“I will write to avenge my loved ones”

Ernaux writes with a sophisticated and direct style.

In previous interviews he has explained that he defined his style when he began writing about his father, a working-class man for whom clear and direct language was best suited.

At the age of 22, he wrote in his diary: “I will write to avenge my loved ones,” a phrase that became his beacon. His goal, he explained in his Nobel Prize speech, was to “eliminate the social injustice associated with the class into which one is born.”

After moving from a rural working-class life to a middle-class life on the outskirts of a big city, she describes herself as an “inner migrant.”

For 50 years she has lived in Cergy, one of the five “new cities” that emerged around Paris, where she moved with her then husband and children. It was still under construction in 1975, and she has watched the city grow around it.

“Here we are all equal: all migrants, from France and abroad,” he says. “I don’t think I would have the same perspective on French society if I lived in the center of Paris.”

The house he lives in today was bought with the money from his first literary prize.

His passion for writing is unbroken. And connecting with her audience is crucial for this modern 85-year-old woman.

When a passionate affair with a married Soviet diplomat ended in 1989, it was writing about the experience that enabled her to recover.

And after the publication of this book, A Simple Passion, there was another consolation: the reaction of his readers.

“Suddenly I started receiving a lot of stories from women – and men too – telling me their own love stories. I felt like I had allowed people to open up and share their secrets,” she says.

He adds that there is a certain amount of shame associated with an “all-consuming” relationship.

“At the same time, I have to say that it is the best memory of my entire life.”

This content was produced in collaboration between Nobel Prize Outreach and the BBC.

Subscribe here Subscribe to our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download and activate the latest version.