“Little Caracas,” the neighborhood of Santiago where immigrants fear deportation if the right wins the presidency

On Toro Mazote Street, right in front of the San Alberto Hurtado subway station, it smells of onions and fried food in the midday sun. Santiago. A number of street stalls sell fruit, cell phone accessories, Christmas decorations, stockings and fresh juices. David offers bananas from Ecuador and explains the difference between the green ones and the riper ones, which he sells for a thousand Chilean pesos (about 1,500 Argentine pesos) per kilo.

“You cut these and fry them and you have the chifle, like the one over there,” he says, pointing to the bag with the already cut and fried banana that they sell in the mini market right in front of it, a few meters from the Alameda.

David arrived from Venezuela four years ago and says he has residency papers “in process.” He survived for months by selling bananas, he says, but before that, since arriving in Chile, he worked “everything.” In shops, on construction sites, in street sales.

Now he has a table under a colorful parasol where he spreads out the bananas. In this block and on Calle Conde del Maule, just a few meters away, you can find street stalls, small shops and delicatessens (here it is called delicatessen). They are mainly served by Venezuelans or Colombians. For this reason, this area of downtown Santiago, near the central bus station, is called “Little Caracas.” And in recent weeks it has been in the news in some local media due to police operations at unauthorized businesses or incidents on the street, such as fights between neighbors or attempted robberies.

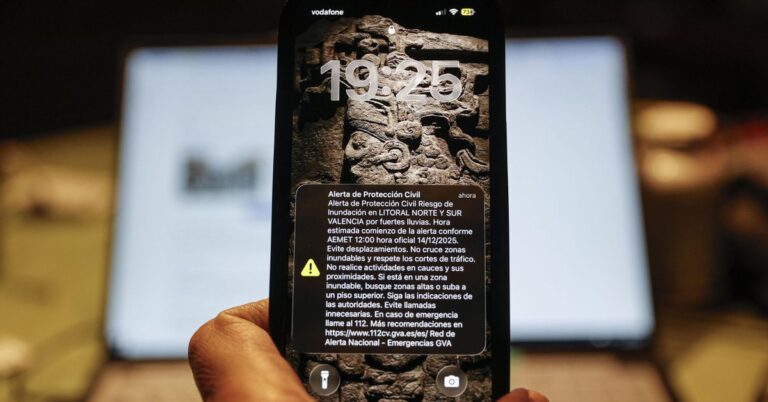

Supporters of José Antonio Kast at the end of the campaign this Thursday in Temuco, Chile. Photo: EFE

Supporters of José Antonio Kast at the end of the campaign this Thursday in Temuco, Chile. Photo: EFE countdown

David now says he doesn’t know what he will do if the right-wing leader José Antonio Kast he achieves the presidency and fulfills it his promise to expel all immigrants who do not have their documents in order.

“You still have 90 days to leave the country,” Kast reiterated on Thursday at his last campaign rally before this Sunday’s runoff election in which he will face the ruling party Jeannette Jara, and if the polls are not wrong, he has practically paved the way to the La Moneda Palace.

The countdown began before the first round of voting. Every day, the candidate of the Republican Party, an ultra-conservative with positions close to Donald Trump, Javier Milei or Jair Bolsonaro, reminded undocumented foreigners how many days remain until March 11, when the new government takes office. He “invites” them to leave early or face prison or expulsion.

In a country of about 18.5 million people, foreigners make up almost 9% of the population. AND It is estimated that around 330,000 people have irregular immigration status.

What is happening in the North is serious and we need a government that will manage the exit process of thousands of illegal immigrants. Some candidates are proposing massive regularizations, we will restore order and compliance with the law. pic.twitter.com/ElkMVHVCDU

— José Antonio Kast Rist 🖐️🇨🇱 (@joseantoniokast) December 3, 2025

Among several customers buying fruit or asking for prices at the stalls on Toro Mazote Street, another man with a Venezuelan accent, tall, robust, wearing white pants and a T-shirt, rushes to David’s stall. He greets, takes five or six bananas, the yellow ones, and puts them on the scales. David demands 3,000 pesos from him. The man pays cash and listens to part of the conversation with this envoy. “I’m paying you because if they fire us, I’ll owe you the bananas,” he jokes. José – not his real name – says he has been working in construction for years. He seems to know the vendors on the block, who greet him like old friends and joke.

Some have lived here for many years, others have only arrived in the last few months. And they are part of the wave of immigrants who entered Chile illegally and who now want to control both Kast and Jara – with less drastic measures – as one of the measures to reduce crime, often linked to illegal immigration and the arrival of groups linked to the drug trade, particularly the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua.

“If they take me out, I’ll go.”says María – not her real name either – as she waits at the checkout at a convenience store on Calle Conde del Maule. Cap with a peak, long, straight hair, he says he is 27 years old and has been living in Santiago for almost three years. She came “with a friend,” leaving her mother and siblings behind in Venezuela.

There he studied administration and accounting Clarion. “But I had to leave school and was looking for a better life.” It wasn’t difficult for him to find a job here. She takes turns with another employee, also Venezuelan, and works eight hours each in this restaurant, which sells food and drinks from seven in the morning to eleven in the evening.

But he admits that he prefers not to walk on the street much at this time. “There is a lot of madness, at night there are some crazy Venezuelans…” he says, without further details.

-No, they don’t steal, we all know each other here. Those who steal are not just Venezuelans. Colombians, Chileans and Peruvians also steal here. There are good people and like everywhere there are thieves. But sometimes they drink, there’s a lot of drinking…

In addition to Venezuelans, María explains, “there are also Colombians, Haitians and Ecuadorians here.” A few meters away is the Los Colombianos shop and also a Peruvian restaurant.

“Everyone lives here, we already know each other,” says María, greeting a ten-year-old girl who comes in with her mother to buy milk and eggs. Some managed to normalize their situation, others did not. María doesn’t have the documents in order. That’s why he repeats: “If they take me out, I have to leave. This is not my country. I have to go back to Venezuela.”