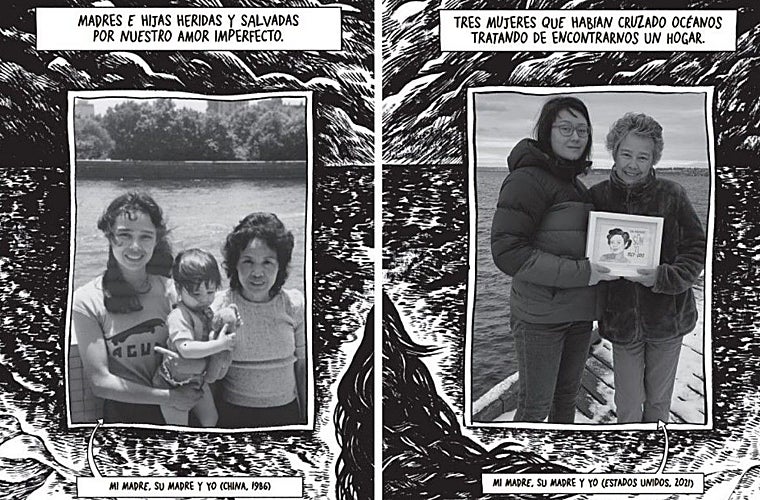

This story could begin in 1958, with a woman publishing her memoirs in China. Her name is Sun Yi, and although she did not suspect it at the time, her book, a bestseller, would be banned throughout the country and she would end up hospitalized at the first psychiatric … Hong Kong: You will never regain your sanity.

Or it could begin in 1970, with the arrival of his only daughter, Rose, in the United States, where she would start a family and understand the meaning of uprooting, distance and bloodless pain. There he will cultivate andsilence and memory.

Or I could start in Alaska. Yes, it could start at the Capitol in Juneau, with a woman who prepares sandwiches for Alaska’s senators and representatives: she has a lot of work. His cell phone has no coverage, as always happens when a cruise ship comes to town and tourists disembark. It is May 5, 2025, a cold day with light rain. Suddenly, a deputy approaches him and says: you won the Pulitzer Prize.

The woman who prepares the sandwiches is forty years old and her name is Tessa Cases. She is Sun Yi’s granddaughter, Rose’s daughter, and she has just become the second person in history to win a Pulitzer with a comic book. The other time was in 1991 and the winner was a certain Art Spiegelman with “Maus”. His is titled “Feeding the Ghosts” (Reservoir Books) and it is the chronicle of his life, that of his mother and that of his grandmother: a reconciliation with his past after three decades of flight.

“That was the longest part of the creative process: the escape,” jokes Hulls, who has just arrived in Madrid from Rome and is carrying a mountaineering backpack. Before sitting down to tell this story, Hulls dedicated herself to the journey alone: she walked the ofrozen oceans of Antarcticasaw an aurora borealis in the Alaskan tundra, crossed the deserts of Ghana cycling, he accepted that he would never have a normal job. But in 2012, when he was further away from his family than ever, her grandmother died. “In Chinese culture, there is something called hungry ghosts: spirits of people who have failed to do on Earth what they were supposed to do and who are condemned to wander eternally across the planet with an insatiable appetite, trying to satisfy their perpetual hunger. As a child, I felt these ghosts in my bones and tried to escape from them, but Sun Yi’s death made me realize that it was impossible. True freedom cannot be found on a distant frontier. To find peace, I would have to face my ghosts,” he writes at the beginning of the book.

— It took almost a decade to complete this book. Is it more difficult to travel to the ends of the world or to the past?

—Now I see that all the trips I took in my twenties were to escape this story. But the hardest journey of my life was returning home, the only place in the world that scared me. And having to dig into my family history to find a way to repair the relationship with my mother. Neither reaching Antarctica nor crossing Ghana can compare to this.

-How was it?

— Well, it’s been thirty years on the run… I understood that I had to investigate the story that broke my family. My grandmother had published a memoir, a bestseller in China, which was never translated into English. I got a scholarship and ordered a translation (she never learned Chinese), and while I waited, I began reading everything I could find about Chinese history from the year my grandmother was born, 1927, to the start of the Chinese Civil War and the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1976. But as I read, I realized that I couldn’t trust everything I read, because the Chinese government had forced people to falsify the information. The more I read, the more I understood that the book had to answer a larger question: how to tell a story when we can’t believe what we’re told.

“The hardest journey of my life was returning home”

— Her grandmother didn’t tell her about her real traumas until late in her life, when her dementia was so severe that her mother stopped giving her antipsychotics. Then he talks about his raped cousin, his hanged uncle, the corpses piling up in the streets.

—When the communist government succeeded in making people doubt their memories: families did not talk about what had happened. One way or another, the Chinese government has implemented the greatest regime of silence possible. Now, it is the children and grandchildren of the diaspora who tell these stories, who ask themselves: why is no one telling them? Those who left have remained silent, but younger voices insist there needs to be more talk about the past.

—Did your family take it well?

—Yes… I had to ask them to tell me these stories from the book, because none of them were written and I had no other way to access them. And when I listened to my family in China, I was very surprised by the fear they still had: they were very afraid when they spoke, even though this had already happened decades ago… In the book, I deliberately did not use their names, because I wanted to respect their fear, the fear of my family. Being in Hong Kong, I understood China’s relationship with its past. I was there and I had with me my grandmother’s memoirs, which are a banned book. I remember showing it to a journalist. I told him: look, it’s a relic of the past. And he told me: be careful, the past is not the past here. This is something that explains what has happened in Hong Kong over the last decade.

—And what will happen with this book in China?

“I don’t think the Chinese government would be willing to agree to a book like this. A Chinese edition has just been released in Taiwan. I’m very curious how this will be received there…

Two photographs of the author with his mother and grandmother included in the book

In the book, Hulls presents herself several times as the protagonist of a western: it is, after all, a story of borders. “I’ve seen a lot of spaghetti westerns,” he says with a laugh. “It’s a visual resource. I use the cowboy metaphor to frame the drama in a story of good guys and bad guys. There is daughter versus mother, because at one time there was a cultural battle between us: silence versus curiosity. And at the same time as it gives a touch of humor to the book, it allowed me to play. Because the book isn’t fiction, I couldn’t change the fact that it was going to be a pretty dark subject, but I dressed like a cowboy… If I felt trapped in a vignette, then all of a sudden I’d get on a horse and ride out,” he explains.

—His pictorial work is very colorful, but here he only uses black and white.

—(Laughs) It’s true: I like bright color palettes and very dense color patterns. And actually, at first, I thought it was going to be a color graphic novel. I started in black and white thinking I was going to digitally color it at some point, but everything ended up being so dense and maximalist that I felt like it would overwhelm the people who saw it if I added color. Black and white serves the story I was trying to tell, which is to look at binaries, oppositions, confrontations, the search for this invisible thread that unites two opposing things.

—’Maus’ is also a black and white story. Did this have an influence?

-Absolutely. “Maus” opened the door to everything that followed: “Feeding the Ghosts” would not have existed without “Maus”. I tried not to re-read it until I was almost finished with the book, so that it wouldn’t influence me too much. But then I came back and the way Spiegelman uses the little notes and follows his father’s story, his family’s story… He was doing something very similar. Graphic novels tend to unite the personal and the political, to exchange everything.

—Have you spoken to him?

—Not yet, but I hope to.

“This book took me off-world for many years. I’ll continue to make comics, but not like this.”

— When he received the award, he declared that he would no longer make graphic novels. Are you maintaining it or do you have a new project in hand?

—I haven’t changed my mind. I learned to draw comics for this project because I saw the potential of the medium as a tool to tell what I needed to tell. But this book took me away from the world for many years and almost destroyed me. I’m not prepared to spend so many years leaving the real world to tell another story like that. I will continue to make comics, but not like this.

-SO?

—I want to use this tool to be a journalist through comics. I want to work in the field, with scientists. What I want to do is use the skills I learned over the nine years of working on this book and in these very remote places to work with scientists; be able to use comics to explain what they do and why it is so important. I like the short format, I like getting out into the world, learning things, explaining things. I work because there is something that makes me curious and that I want to understand, I never felt that I had something special, that I had more stories in me that I needed to bring out.