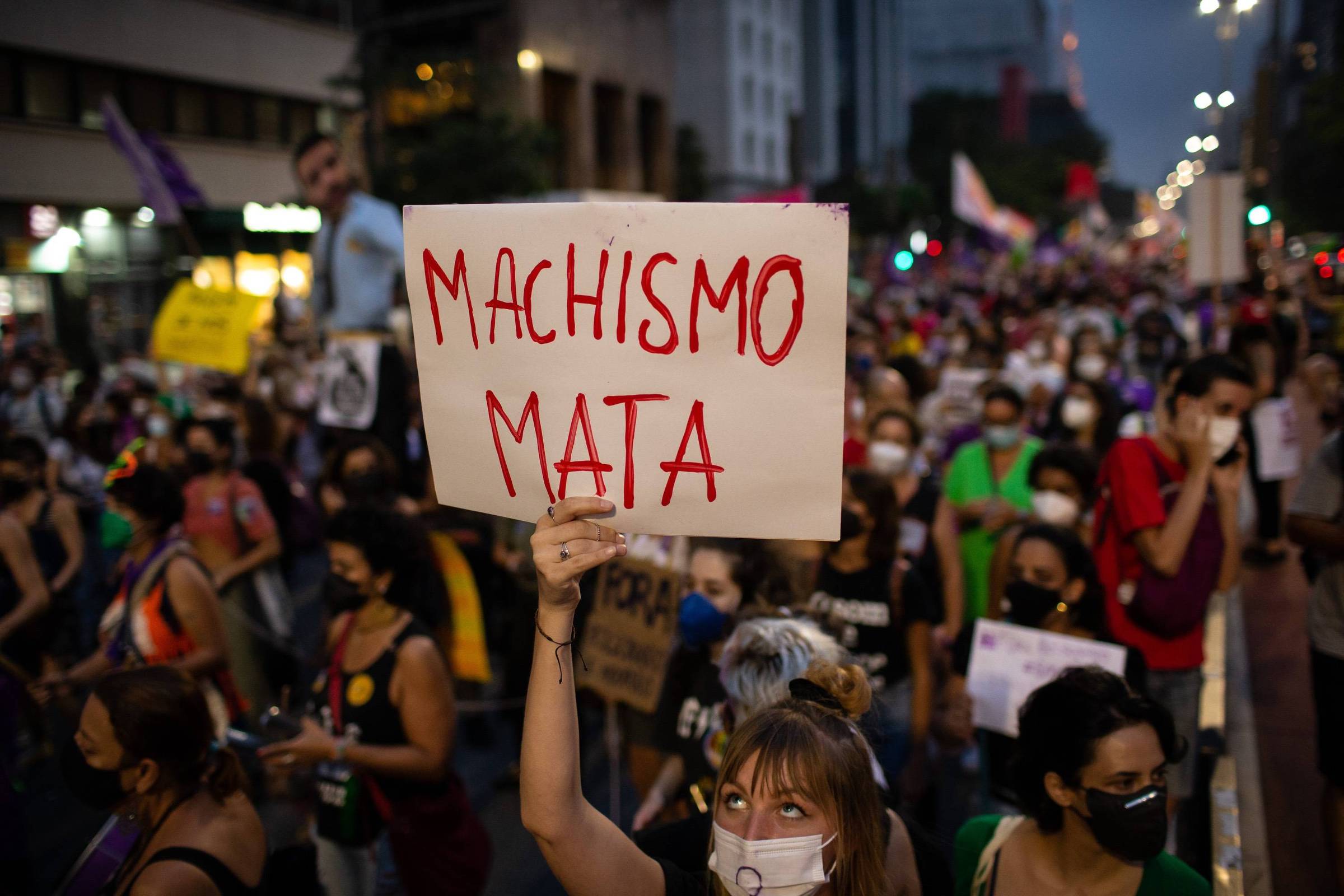

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence as the use of physical force or power, actual or threatened, against oneself, another person, a group or a community, resulting or likely to result in suffering, death, psychological harm, hindered development or deprivation. There are different systems of oppression: according to gender, race, social class, sexuality, level of poverty, age, etc.

Family violence is certainly the most paradoxical of all, because it emanates from those from whom we expect the greatest protection and from whom we should not expect any form of mistreatment.

There are different forms and degrees of cruelty in the context of domestic violence, especially against women, who are culturally subject to dependence on men and generally have very little independence and autonomy, and are always and allegedly subject to the protection of a man – whether he was her father until marriage, when she then belonged to her husband, or to her brother-in-law or brothers if she remained widowed or remained single.

It was only in 2006, with the Maria da Penha law, that mechanisms appeared to combat domestic and family violence against women, without other forms of violence going beyond physical and verbal brutality being cited, as is the case with psychological, sexual, moral, economic and real estate violence. These already existed, but they did not have names and were therefore not directly identified.

Property violence is extremely serious given its consequences, since the lack of economic independence often forces women to remain in a state of permanent aggression and, therefore, unable to break the cycle of brutality. A power which is often exercised at the height of the emotional relationship, the controller taking care never to give more money than is strictly necessary for subsistence and to grant a certain freedom to the woman, who always needs to find herself in a disadvantageous situation.

Due to real estate or economic violence, victims have restrictions in handling their money or property; do not have access to work or profession; and financial abuse increases in marital crises, as they are still without money and without access to the assets they share, they face lengthy legal proceedings and fraudulent misappropriation of assets.

These deviations cause economic and financial asphyxiation of women, whose procedural tactics push them towards other forms of punishment, physical and emotional exhaustion and intimidation, giving rise to procedural violence with legal disputes. This is characterized by the use of the justice system to destroy the last forces of belief and hope in justice – which still live in the expectations of a wife or partner in their unequal struggle, but whose expectations become even worse when the justice system itself imposes procedural difficulties.

This is the case, for example, when the payment of legal costs is favored to the detriment of legal costs, or when essential violations of tax, banking, financial and judicial secrecy are denied – essential proof in actions of food and real estate sharing to combat fraud, in an attempt to overcome the financial and patrimonial arrogance of a resentful partner.

Institutional violence emerges from this common procedural scenario. This is another equally drastic and discouraging form of violence, which prevents women from exercising the rights provided by law under the institutional pretext that the violation of confidentiality should only be permitted in criminal matters – as if violence against property was not a crime characterized by the Maria da Penha Law itself and as if, with these procedural obstacles, domestic violence did not encounter new and unacceptable cycles of oppression.

TRENDS / DEBATES

Articles published with a byline do not reflect the opinion of the newspaper. Its publication aims to stimulate debate on Brazilian and global issues and reflect different trends in contemporary thought.