COP30 marked a silent shift in international climate policy. For the first time, caution has been formally integrated into the decision-making frameworks of the global climate regime.

According to Georgia Haddad Nicolau, a specialist in care studies and director of the Procomum Institute, care is about public services, social protection and the daily work that sustains life, from health care to food, from education to community care.

The inclusion of the care economy in the COP’s Just Transition Work Program and the broader Belém Gender Framework signals a paradigm shift. Tackling the climate emergency requires much more than technology, green innovation and physical infrastructure. It is essential to structure systems capable of protecting people before, during and after extreme events.

For decades, climate resilience has been associated with works, mitigation targets and technical solutions. But floods, droughts and heatwaves also overwhelm health, education, social assistance and food systems.

Therefore, the daily needs of those affected, especially the most vulnerable, rely on community networks and unpaid care work, carried out primarily by black, indigenous and peripheral women.

The report “Centering Care in Climate Finance”, by Jamaican economist Mariama Williams, financed by IDRC, the Canadian public center for promoting research for development, makes it possible to assess the situation.

The study shows that although the climate crisis directly puts pressure on essential services, less than 5% of international adaptation funding is allocated to health, and around 2% to education.

The material foundation of resilience remains outside investment priorities, even if it supports the survival of the most exposed populations.

The central proposition of the study is to treat health care systems as climate infrastructure. Territorialized health services, comprehensive education, social protection networks, school meals and community facilities reduce human losses, avoid forced displacement and increase adaptation capacity. These are therefore structures without which other public policies do not work.

Some countries have begun to translate this understanding into formal commitments. Mexico launched its NDC 3.0 (Nationally Determined Contribution) providing explicit references to care, particularly in the adaptation axis, linking climate policy and social protection.

Cambodia also appears among the first to include the subject in its national plans, an experience officially presented at COP30.

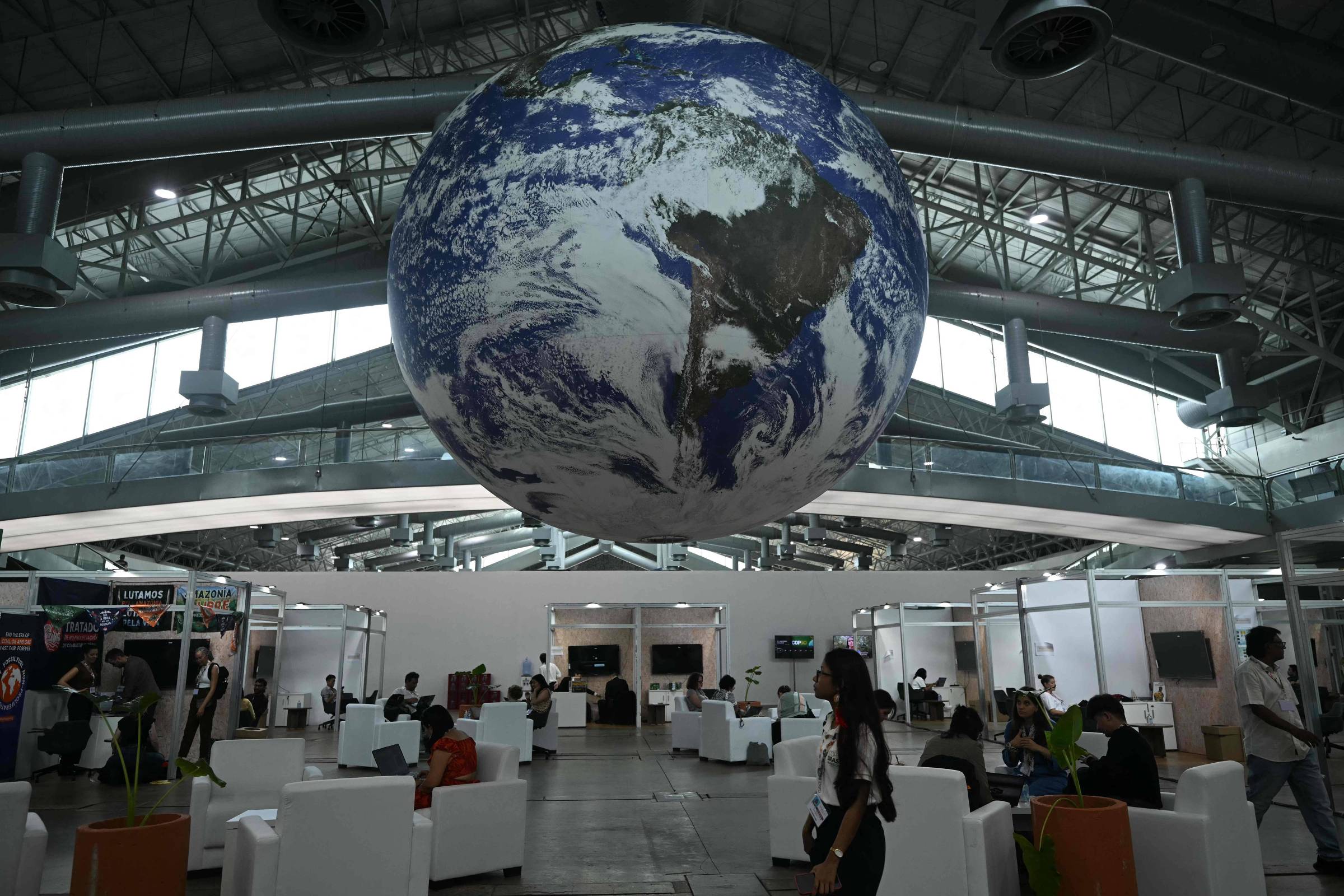

This advancement gained institutional visibility with the creation of the Care Pavilion, which brought together governments, organizations and researchers to discuss climate, gender and social justice. For the first time, care no longer occupies a peripheral place in international negotiations. But it remains out of competition for resources. The adaptation work programme, for example, does not mention care.

Resilience depends above all on systems capable of protecting lives. And this certainty must be present not only in political debates, but also in concrete actions.

PRESENT LINK: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click on the blue F below.