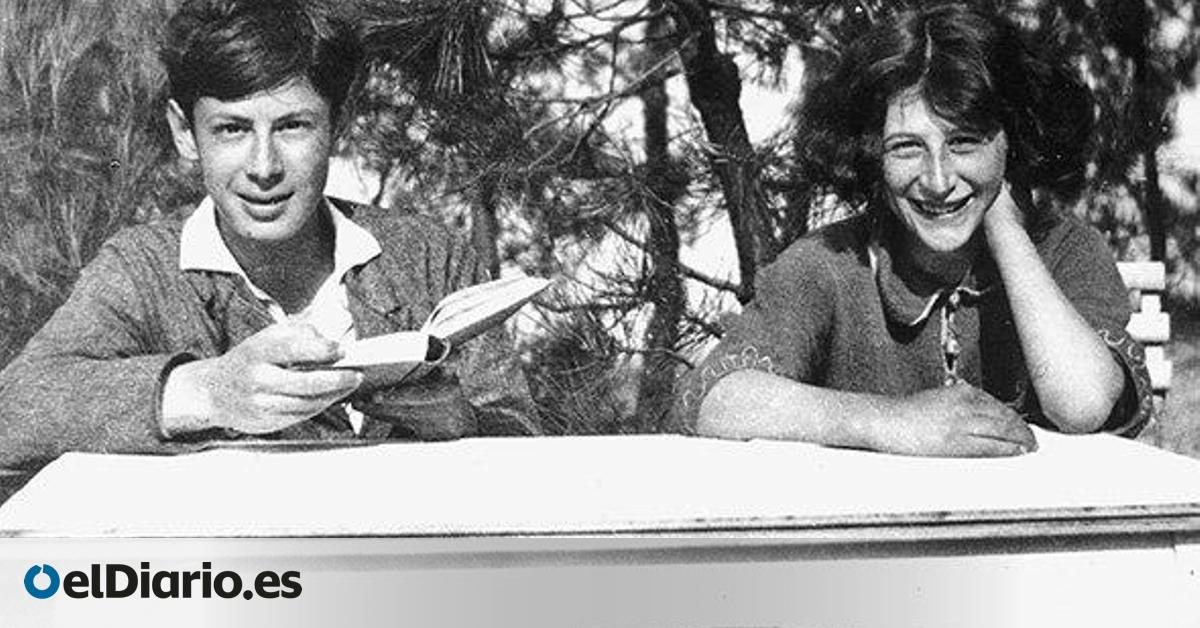

“Love is not a comfort, it is a light.” This sentence from the philosopher Simone Weil (1909-1943) is used in the physical edition and gives its name to LuxRosalía’s new work. The Catalan artist claims that Weil was one of the great influences on this album, adding to the growing interest in the thinker’s work in recent years.

Philosopher and activist of French origin, Simone Weil combined thought and action throughout her life. In his work he mainly reflected on topics such as human suffering, misfortune or working conditions. But, although many people don’t know it, he also had a real interest in mathematics. “It is the same truth that penetrates the senses through pain, intelligence through mathematical proof, and the faculty of love through beauty,” he writes.

Simone had been in contact with mathematics since childhood. He was particularly interested in classical Greece and 17th-century France, where mathematics was seen as an integral part of thought. According to the estimates of mathematician Laurent Lafforgue, Fields medalist in 2002, Weil devoted around eighty pages of his notebooks to reflections on this discipline, to which are added various notes and exercises on geometry, mechanics or differential calculus, among others. In addition, Simone Weil was able to learn directly about contemporary mathematical research thanks to her older brother André, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century.

Thanks to him, Simone attends some of the most exclusive mathematical meetings in history: the meetings of the secret Nicolas Bourbaki group. Bourbaki, of which André was one of the founders, sought to reconstruct pure mathematics from scratch, axiomatically, based on set theory and some basic notions, and had an enormous influence on the teaching of this subject.

Mathematical discussions are also very present in the correspondence between the brothers. Responding to Simone’s request to explain his recent research, André, who was in prison for failing to fulfill his military obligations, wrote a fourteen-page letter describing a fundamental connection between three seemingly disconnected mathematical fields: geometry, curves over finite bodies, and number theory.

In geometry, we study objects called Riemann surfaces: spheres, tori (the donut-shaped surface), or other surfaces with different numbers of holes.. These forms can also be described as solutions of certain equations. For example, solutions (x, And) of the equation And² = x³ – x describe a torus, if we consider points (x, And) of a mathematical space called complex plan.

If solutions are sought (x, And) to this same equation within integers (whose properties are studied in number theory), instead of a torus, we obtain a handful of isolated points. Thus, the same equation can give rise to very different objects: a set of points, a curve or a surface, depending on where we look for the solutions. This idea, which André emphasizes in his letter, is the key to the approach to modern algebra: we first pose an equation, then we decide where to look for the solutions. The goal of his research was to use this flexibility to find a bridge between geometry and number theory.

Instead of looking for solutions in real or complex numbers (which have an infinite number of elements), he studied them in other sets comprising a finite number of them: finite bodies. André focused in particular on the study of certain functions, called rational, which assign values to geometric figures defined on finite bodies, and discovered that they have a behavior similar to that of numbers. Exploring these properties allowed him to translate results from geometry into number theory and vice versa.

Throughout his career, André refined, formalized, and structured the ideas outlined in the letter to Simone into what we call the Weil conjectures, which decisively promoted algebraic geometry and number theory in the following decades. In an attempt to prove them, Alexander Grothendieck, one of the most important figures in 20th century mathematics, laid the foundations of modern algebraic geometry. Finally, in 1973, Pierre Deligne completed the proof of the conjectures using the techniques developed by Grothendieck, for which he received the Fields medal (the “Nobel of mathematics”) in 1978.

Enrique Aycart Maldonado He is a predoctoral researcher at Complutense University of Madrid and member of Institute of Mathematical Sciences (ICMAT)

Editing and coordination: Ágata Timón García-Longoria (ICMAT-CSIC)

Fractal dimension It is a space of Institute of Mathematical Sciences (CSIC-UAM-UC3M-UCM) in which a mathematical vision of current events is proposed by specialized research staff.