Sundays It’s a wonderfully ambiguous film. How lucky.

Long live cinema, die parody.

Alauda Ruiz de Azúa makes us smart. This reveals us. It puts everything in our eyes. In short, at least the responsibility of reading the world. It’s always been like this.

The film, which, as you already know, is about a minor who studies at a religious school and says she wants to be a cloistered nun to the stupor or indifference of her disturbed family, is very playful, very alive, and allows itself to be completed by our traumas and desires, by our belief system.

Is this sirloin dish delicious or is salivating over it an act of sadism?

From what I know, it will depend on whether we are vegan or not.

I eat flesh and also respond to the impulses of the spirit: let’s talk.

How tense is the subtlety of Sundays and what height this gives to the debate. Activate some of my pleasure points. Practicing Catholics say it is a pious play (this is, of course, due to the shameful cruelty with which fiction has accustomed them to cultural mockery: celebrate any respectful treatment of infrequent people).

Atheists say it’s a horror film.

I am neither one thing nor the other. Atheist by no means, but also not religious in the orthodox or institutional sense, so I contemplate the beauty of cathedrals and make love and unamunian agreement and write between two waters, like Paco.

Maybe that’s why I see the film the way I do. Understanding her own and others’ feelings and interested in the mystery that lives behind things, but critical of the official Church, its elitist aura and its permanent accusing finger, a bastion of anti-intellectualism and the dogma that impoverishes us.

Catechesis in Spain never ends.

When and how can I distinguish that Ruiz de Azúa questions religion and its tentacles?

Come on, there are spoilers.

1. The language trap

During the nearly two hours of filming, I seriously doubt that God called the girl. In other words: I value possibility. What does anyone know?

But something happens when the girl loses her grandmother, that is, her second mother (she had already lost her first and was already an orphan for all intents and purposes, after the deafness of an indifferent father who only thinks about his new girlfriend). He mourns his death on his knees. Seek comfort. And experience an epiphany.

There’s desperation in the girl’s eyes (We will also have to see why God is so fond of showing up when you are desperate and not when you are hopeful).

Desperation is an impulse, a springboard.

You don’t know if the girl is seeing or is struggling to see and she draws God’s scratches on her heart like someone screaming in a backyard. What should we expect? We know almost nothing about the invisible. It just exists.

Then the girl speaks. Appeal. Send your words of love to the Lord. He declares himself in such a beautiful and radical way, with so much personality. It’s the first time we actually hear her speak in the entire film: the first time he expresses himself fluently. It’s about time, dammit.

She wants to be looked at by him. She wants to be loved by Jesus now that almost everyone has abandoned her. She is alone, floating in uncertainty. Dream about a hand rest. She needs God or she will be alone forever because the world is not enough. For whom is the world enough, really? I don’t know.

I hear her speak and it moves me. The girl takes control of her speech and that clears me up, makes me believe. I see it autonomous. She thinks and feels for herself.

A human being is his words. In the words of a human being there is freedom. We are only ourselves if we create our own speech: the only possible photo of our brain, of our heart.

You know you are not domesticated because you choose your vocabulary and order it to exist from word to mouth. This is why in dictatorships there are prohibited concepts. Prohibited phrases. The government of language is the government of women and men.

I think about all this as I listen to her speak, and voilaI feel relieved, I detect freedom in this girl. The girl is not captured, I tell myself, the discernment and passion are hers and genuine and not copied from the voice of the spiritual advisor or the prior.

But then the girl finishes her speech… and starts from scratch, identical, word for word! He repeats in a block. It’s a litany! These are learned words: tired, abused. Instilled words. Words from others. Sectarian words, zombies.

Here I understand everything with dread. The girl was kidnapped. He is not even free to choose the words with which to convulse with love. Nothing is his anymore, not even the words he gives himself to. He lost his individuality. She is gregarious. He is a victim.

She looks at the crucifix and says, very eloquently, defenseless as she is, weak and without firm roots: “You are my father, you are my father”. I understand. After the officer’s failure, God is his adoptive father. God does not move. God will not go away. He doesn’t.

I think about what he said Goethe. It is more powerful to feel loved than to feel strong. The human being, of course, is a brilliant creation. If he has no love, he will conceive.

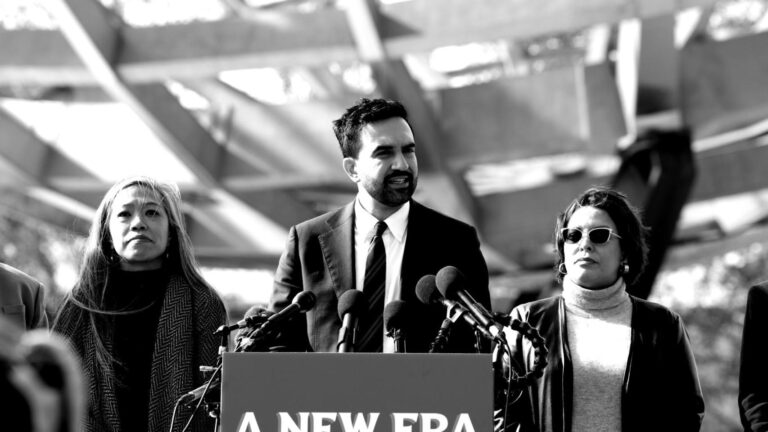

Frame of Sundays.

2. The subtle Inquisition

In the same vein as the study of language perversion, I listen carefully to how the spiritual advisor and the prior speak to the girl. They gained their trust behind the backs of their family, their guardians.

How clearly do we understand that it is intolerable for an adult to touch the private parts of a minor, But how many doubts arise about that adult’s intimate relationship with the child or adolescent if the influence is verbal?. The protagonist had been secretly talking to these members of the Church since she was twelve years old. Did they help her? Did they drive? Did they love her? Did they recruit her?

We only have two conversations in the film to hold onto to get to the truth. And both are governed by questions. Neither the advisor nor the prior directly tells the girl what she should do or what she should believe, but they take her underground to a place.

Oh, I think. How many questions, one after another, what powerful curiosity these people have, man. The questions, somewhat complicated but ambiguous, sweetly corner the girl. They accompany her subtly, without putting pressure on her.

They are both very intelligent. Great interviewers! Lots to learn from them!

What inquisitors, I say to myself. The Inquisition, I think later. I smile and the little pieces fall into place.

The religious men and the girl have no real conversations. They conduct an interrogation. She responds.

3. “I will pray for you”: forgiveness or pride?

Another moment (another detail) in which the film made me take a stand.

It’s disheartening to think about the coldness of creation. The girl doesn’t do anything for anyone. She doesn’t care about anyone but herself: her aunt, her little sisters, her grandmother, her friend, the choir boy are worried about her. The father makes it clear (that he’s not there to talk either) when he says: “The world doesn’t revolve around you.”

The girl is lost in thought. He can’t look around. She is blind. It’s a giant wound. He gains discontent as the filming progresses, he hones his selfishness. She is incapable of tenderness. He talks so much about love and ends up not knowing how to practice it.. Daughter, wake up.

Film frame.

Cloistered nun, ruminates. I wonder if a God who separates us from others is good. I wonder if it is desirable to have a God who isolates us, who makes us feel chosen (part of an elite, of the called) and makes us deaf to the pain of others.

Why would God want us for himself? Why wouldn’t God want us to multiply our love, to improve the lives of others? How much better a missionary nun would be. That’s when I start to take it seriously.

At the end of the film, the girl is already a sociopath. The aunt, who tried to respect her process and dedicated herself to her love (after all, she is the one who carries, picks up, supports and takes care of her), is mistreated. She is marginalized. It is ignored. It is ignored.

She becomes frustrated and explodes, broken with pain. And the girl sees her crying and not a muscle in her face moves. “I will pray for you,” he tells her. And he leaves. What does this girl know about mercy? Did you understand something?

Frame of Sundays.

There are Catholic friends who find in this final image anger versus forgiveness, anger versus peace. I disagree: they were too literal. The girl is arrogant and feels morally superior.

What God is it that elevates him above the rest of the creatures of creation?

The girl deals with dogma self-confidence. The unity of the Old Regime. It is said to be unquestionable. “That’s how I feel and that’s how it is.” There is nothing to debate here, there is nothing left to talk about.

I suspect people like institutional religion so much for the same reason they like dogs (more than humans): because you don’t have to stop and negotiate anything. Thought and criticism are out of place. There is a vocation for submission.

However, in religious matters, the people are the dog and the God of the Church is the owner.