A new comprehensive genetic study just published in Nature has called into question some of the most entrenched dogmas of evolutionary biology: the first complex cells appeared a billion years earlier than previously thought. And they did, moreover, … in a world where there was not yet enough oxygen.

Until recently, science was convinced that the emergence of complex organisms, which eventually gave rise to animals and, ultimately, to us, occurred relatively recently, about 630 million years ago, in a sudden “burst” of biological creativity. But the new study, led by the University of Bristol, forces us to reconsider much of that history.

And it seems that the path to complexity was not some kind of “final sprint” of nature, but rather a slow, tortuous and above all extremely ancient marathon. The “machinery” of complex life, in fact, began to develop almost a billion years earlier than we thought, and this in conditions that we until now considered impossible: in a suffocating world devoid of oxygen.

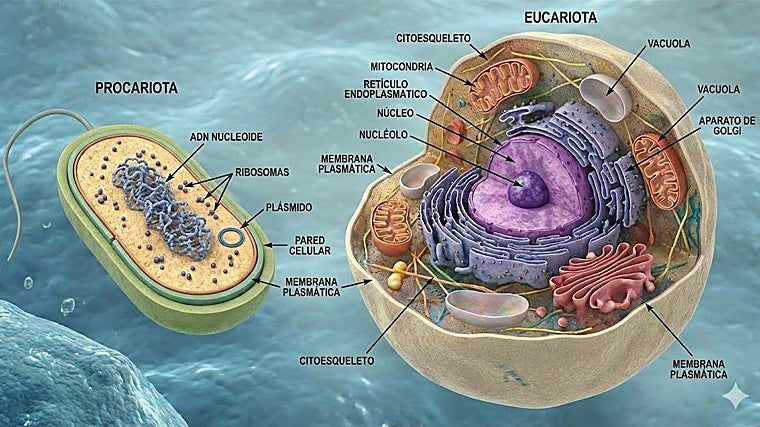

Prokaryotes and eukaryotes

Generally speaking, there are two different types of life on our planet. On the one hand, there are prokaryotes: simple unicellular organisms, such as bacteria and archaea, which are distinguished by a crucial characteristic: they do not have internal divisions. Its genetic material, in fact, is dispersed throughout its interior, without differentiated structures. It would be like a one-room studio: small, efficient, but very simple. Prokaryotes were the first to arrive, they have been there since the beginning and are estimated to have appeared over 4 billion years ago.

And on the other hand, there are, we are, eukaryotes. This group, which appeared on Earth between 1,500 and 2,000 million years ago, includes algae, fungi, plants and of course all animals, including us. Eukaryotic cells are immensely more sophisticated. And if prokaryotes are a “study,” eukaryotic cells are homes: they have specialized rooms (organelles), an armored command center where DNA is stored (the nucleus), and their own power plants (the mitochondria). Without them, complex life (animals and plants) could never have developed.

The path to complexity was not some kind of “final sprint” of nature, but a slow, tortuous and, above all, extremely ancient marathon.

Now, how and when did a simple bacteria make the “leap” to become a much more complex eukaryotic cell? Classical theory told us that this happened a “short” time ago (in geological terms) and that it was previously necessary for the atmosphere to be filled with oxygen to provide the energy for this change. But the Bristol researchers, along with collaborators from the University of Bath and the Okinawa Institute (OIST), found this idea to be false.

To do this, they turned to a technique known as “molecular clocks,” analyzing hundreds of gene families to trace their history over time, like someone following breadcrumbs through a forest to find the origin of the path. So, by combining this genetic data with the fossil record, the team created a tree of life with unprecedented temporal resolution.

The big “leap” of life

The main conclusion of the study is a real revolution: the transition to complex life began 2.9 billion years ago. That is to say more than a billion years earlier than expected. But the most surprising thing is not only this result, but also the order of the factors. Because until now, it was known that the primitive cell had first acquired the mitochondria (the energy plant which uses oxygen) and that, thanks to this “shot” of energy, it could then develop its complexity (nucleus, cellular skeleton, etc.). This is the so-called “mitochondria first” hypothesis.

But the Bristol team’s data paints a completely new scenario that the researchers have called CALM (Complex Archaeon, Late Mitochondria, or Complex Archaeon, Late Mitochondria). According to this model, our microscopic ancestors had already begun building complex structures, internal skeletons, and membrane transport systems long before the arrival of mitochondria. That is to say, life did not wait for the installation of the “power station” to start expanding the house. Structural complexity preceded energy complexity.

And all this without oxygen

These discoveries have implications that shake the very foundations of geochemistry. Because if these first steps towards complexity occurred almost 3 billion years ago, it is because they took place in anoxic oceans, completely devoid of oxygen.

“The ancestor of eukaryotes – explains Philip Donoghue, paleobiologist at the University of Bristol and co-author of the study – began to develop complex characteristics about a billion years before oxygen was abundant.” In fact, mitochondria, which today allow us to breathe oxygen, arrived much later and curiously coincided with the time when levels of this gas began to rise in the atmosphere.

Difference Between Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Cells

Of course, this will also change the way we view life on other planets. Because if it turns out that complexity can arise in worlds without oxygen, the range of places where we might find “advanced life” expands considerably.

Until the publication of this study, the chronology used was rather conservative. It was assumed that bacteria dominated alone for 3 billion years and that only about 635 million years ago, after a global increase in oxygen, complex life took off for good.

Some previous clues

However, despite the novelty of the Nature study, we already had clues that something was wrong. And, as ABC has previously published, there are intriguing antecedents, such as those discovered in July 2024 in the Franceville Basin, Gabon. There, a team led by Ernest Chi Fru, of Cardiff University, found fossils of supposedly complex organisms dating back to 2.1 billion years ago.

The discovery, considered a “failed experiment” of nature, suggests that life attempted to make the “leap” to complexity much earlier, taking advantage of a temporary spike in oxygen caused by underwater volcanoes and cyanobacteria, but “turned around” and died out when conditions deteriorated.

The new genetic study does not necessarily contradict the existence of failed experiments like Gabon’s, but rather gives them a much deeper theoretical framework. This tells us, in effect, that the genetic machinery at the origin of complexity did not appear out of nowhere, neither in Gabon 2.1 billion years ago, nor 600 years ago, because the genetic “bricks” necessary for the construction of complex cells were slowly cooked well before, 2.9 billion years ago.

Therefore, what Chi Fru once called a “failed first attempt” may actually be one of the first visible physical manifestations of this long-invisible genetic process that the University of Bristol has just revealed. Life was just a repetition.

Why are we taking so much time?

But if machines started working 2.9 billion years ago, why did it take us so long to see large animals and plants? Gergely Szöllősi, another author of the study, summarizes it with the concept of “cumulative complexification”. In other words, you can’t build a skyscraper in a day.

In fact, the evolution of complex life was not a one-time event, but an extremely slow process. It was first necessary to “invent” the internal tools (the nucleus, the cellular skeleton, etc.) in a world without air. We then had to wait for fusion with a bacteria which would give rise to mitochondria. And finally, we had to wait even longer for the planet itself to change, to fill with oxygen, so that this machinery could operate at full capacity and create the biodiversity we enjoy today.

The old idea that Earth was a boring place, inhabited only by “dumb” bacteria for most of its history, seems doomed. In the depths of these dark, oxygen-depleted oceans, nearly 3 billion years ago, nature was already silently working on the design of the cell that, centuries later, would give rise to the creatures trying to understand it.