After extolling the characteristics of virility throughout his government, from the “athlete story” cited in the Covid-19 pandemic to the “unbreakable” and “immortal” medal given to allies, Jair Bolsonaro (PL) exposed fragility by highlighting health problems that would put his life at risk in prison and attributing the attempt to break his electronic ankle bracelet to an epidemic.

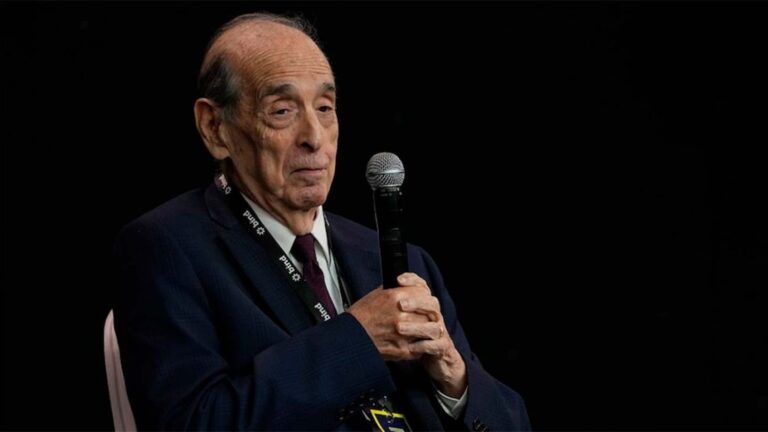

For psychoanalyst Christian Dunker, 59, this is another side of the same coin in the rhetoric about strength, victors and power.

“We can believe that there has been a substantial change, but it is the same discursive discourse. If things do not work, there is a change of pole, and the discourse of praise of virility is reversed.”

In an interview with Leaf — granted before Bolsonaro chose one of his sons, Senator Flávio Bolsonaro (PL-RJ), to run in the 2026 elections and the former president’s defense requested urgent authorization for surgery due to an inguinal hernia — Dunker says he considers Bolsonaro dead, “as a political hero,” although the same cannot be said of Bolsonarism.

“The character (Bolsonaro) is dead, but the possibility of having a new less pyrotechnic, less exaggerated alliance remains very latent.”

Dunker also explains how the discourse on virility is closely linked to politics and also believes that Minister Alexandre de Moraes, of the STF (Federal Supreme Court), also personifies the discourse of the virile hero, this time a “sleeping hero, quieter and rational”.

Former President Jair Bolsonaro seems to have gone from a discourse of virility to one of weakness. How do you evaluate the change? It may appear that there has been a substantial change, but it is the same discursive discourse. If things don’t work, the poles shift, and the discourse praising virility is reversed.

The idea of someone being fragile and in need of help arises, because weakness is the opposite of strength. The discourse is therefore the same: that of strength and weakness, of winners and losers, of those who can and those who are powerless.

A second point is the strategy without strategy that appeared in the Bolsonaro government and appears now, in the defense work (of the politician plotting a coup). At the time of government, speeches composed of back and forth, contradictions, seemed to test the effect of what was proposed and then continue or retreat.

The episode of the (attempt to break the) anklet is somewhat reminiscent of what Freud described as the logic of the leaky cauldron. In the unconscious, several ideas often coexist at the same time, even if they are contradictory.

The story of the logic of the leaky cauldron is more or less this: one person lends a cauldron to another, who returns it leaky. The one who lent said: “Listen, the cauldron is leaking. The other person gives three answers. First: “you never lent me that cauldron.” Second: “it was already broken when you lent it to me.” And third: “I never gave you back.” There are three answers that are individually relevant, but taken together indicate something is wrong.

This is what is happening in the defense of the former president. To try to chart a path to clemency, we look for the narrative that can become the most popular or effective.

What would be the psychological implications of this apparent change in discourse for Bolsonaro and allies? For allies, the implication of this aspect of fragility is curious, because it is a pole that was obscured when Bolsonaro was in power: the pole of pity, empathy, magnificence or temperance.

Previously, many complained about how the former president viewed his opponents as enemies to be ruthlessly eliminated. What we have now is a reversal to the side where the person needs an explanation for what happened.

The idea emerges while he is the victim of relentless and atrocious justice. This idea was obscured in the first phase of this speech, but it now appears as the solution for those who saw in Bolsonaro a great ideal leader, a sort of savior father.

What happens when daddy falls? We must pity him, show understanding and say: “the law applies to everyone, but for those who are exceptional, more indulgence and temperance are necessary”.

Can you explain a little more what is changing with the discourse on the epidemic? What was once leaky cauldron logic now appears to be some kind of mental disorder. There is an appeal, perhaps to you, perhaps to others, that this alternation of poles ultimately reflects a somewhat calculated idea that an epidemic, a crisis is occurring.

The idea is conveyed that a person in this state needs to be welcomed and not punished. What’s happening there is that everyone seems to have their own idea of what an epidemic is, which creates a kind of popular absolution.

Basically, the idea of an epidemic reflects very different psychological states. Some might say that a panic attack is a type of epidemic. Others, a psychological crisis or a very intense state of dissociation, although they are clinically very different.

How does the discourse on virility intertwine with politics? (Former President Fernando) Collor, for example, said he had a bad case. He was elected maharaja hunter because he was a “real man”. This idea is part of the rhetoric which associates the family – the natural power, the father – with force, in the sense that problems must be confronted with violence.

This creates protégés and enemies, leading to the separation on these two levels that many have called polarization, but which is an effect of discourse.

When such a process is transformed, there are regressive reactions and reversals. Manly and heroic leadership gains a certain place, but when it enters a more institutional level, it is not approved.

And it’s not just Brazil: (montage of Russian President Vladimir) Putin riding a bear, (Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor) Orbán saying “I’m a real Hungarian” and (US President Donald) Trump championing the idea of ”great manhood again” are other examples.

Does the fall of Bolsonaro generate a decline in this discourse based on virility? There is a stranger there. There will be a narrative that continues to adhere to this discourse, but by reversing the pole. She will say: “Look, Bolsonaro was defeated by an even tougher guy, who is Xandão (Alexandre de Moraes, minister of the STF)”.

From now on, the only thing that changes is the type of hero: it is the disguised hero, more silent and rational. This hero is less ostentatious, but, deep down, he puts on a show. Many will see it: we continue in the era of men and their superpowers.

Bolsonaro was arrested and this did not give rise to major demonstrations. As a political figure, is he already dead? As a political hero, yes. This corresponds to both the personal and public strategy that we follow within the family.

This fits into a typical problem of the political death of these characters, which occurs when they are unable to leave a legacy, to transmit their power.

There is a clear vacancy as to who “Bolsonaro 2” is, even if there are a lot of people competing, which is part of the game. He is dead, but not the Bolsonarista discourse. The character is dead, but the possibility that you have a new, less pyrotechnic, less exaggerated alliance remains very latent.

There is still a certain percentage of fervent Bolsonaro supporters. Like Mr. you see that? A critical theorist named (Theodor) Adorno conducted postwar research trying to understand if there was a personality trait that explained why people adhered to fascism.

It reaches a very similar number (to that of the more fierce Bolsonarists), in a proportion which remains more or less regular, between 9% and 14%, of people incapable of backing down.

They cannot recognize mistakes, mistakes and do not tolerate doubt. They adhere to an idea of a natural power structure. In this logic, it is natural that the elders command, that the father, the man, commands.

It’s a kind of world order. When we adhere to this mode of operation, it becomes very difficult to tolerate changes, whether they are in our favor or against. Change and the idea of transformation becomes a problem. When this accumulates, there is what we call a conservative revolution.

The number of people operating in this way is more or less constant. The great danger comes when they manage to take over the silent majority and expand beyond their own limits.

What else would you like to comment on? Bolsonaro has put in place a series of rules very contrary to what would be the most progressive policy on mental health. This represented an enormous risk of regression of the asylum, and Michelle (Bolsonaro, former first lady) has a certain infiltration in this theme, linked to disability and autism. And look what happens: the subject now has an affinity for his argument that he suffers from mental health issues.

He proposed the expansion of therapeutic communities, the reduction of Caps (Psychosocial Care Centers) and investments. He proposed a series of things, some were adopted, others not, but the damage was considerable.

What happened was that this policy continued. No one saw it, but she continued. This has given rise to several conservative groups that could gain very strong political influence among all those who need mental health care and feel helpless. These people can form a suffering public, easily captivated by a conservative orientation.

X-RAYS | Christian Dunker, 59 years old

Psychoanalyst and professor at the Institute of Psychology of USP (University of São Paulo), with post-doctoral fellowship at Manchester Metropolitan University. Twice winner of the Jabuti Prize for “Structure and constitution of the psychoanalytic clinic” (Annablume, 2011) and “Mal-Estar, suffering and symptom” (Boitempo, 2015), he is also the author of the books “The art of loving” (Record, 2024) and “Estilo de Lacan” (Zahar, 2025).