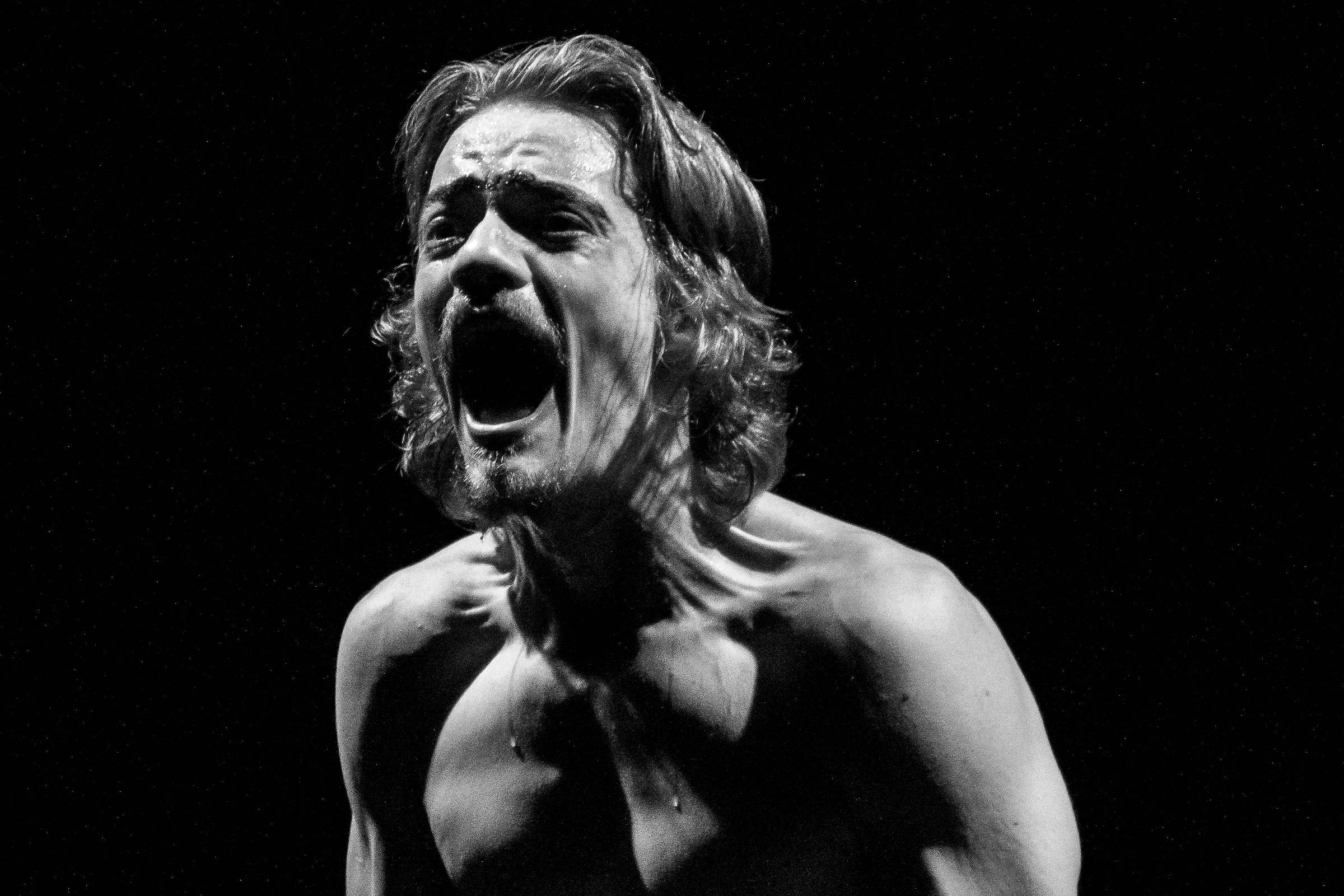

“Joãozinha Desviada” is an autofictional monologue that transforms mourning into a stage act. The play is born from absence: the death of his father, Juracy, with whom the author and actor João Ricken had not spoken for a year. Physical (between cities) and emotional distance become raw material for theater. The stage becomes the place of conversations never had, a ritual space where desire is shared.

The dramaturgy avoids melodrama. Instead of portraying the father as a villain, the series shows him as the product of a masculinity that silences affections. With humor and irony, Ricken investigates this emotional legacy, wondering if his father also carried his own unlived pains and desires.

And here the central metaphor appears: the transformation into an ant. “Joãozinha” is not just a reduction of João; it’s a gender journey, a twisted identity. The ant, a collective and underground being, allows us to talk about mourning in a playful and symbolic way. Everything happens as if, by becoming an ant, the character could visit his father on earth, descend to the tomb without fear, and even question the rigid structures of the human world.

Throughout the play, cachaça becomes an element of ritual. The actor offers the audience a drink and toasts “to desire”. The gesture is simple, but powerful: it takes death out of the solemn environment and places it on the bar table, on the territory of life. The public becomes complicit, an ephemeral community of those who also tolerate absences.

The time spent on stage is not linear. It follows the logic of memory: jumps, repetitions, flashes of affection and silence. The setting is the character’s mind, a place where pain, fantasy and acid humor coexist.

“Joãozinha Desviada” is, ultimately, an act of reconciliation. Not with the father who left, but with the story itself. And, by sharing this journey, the show welcomes those who watch, reminding us that mourning, like theater, is a space where the living continue to speak.

Three questions to…

…John Ricken

In what way did writing the piece function as “a conversation that never happened” with your father, creating a listening experience not possible in real life?

When my father died, we hadn’t spoken to each other for a year, due to an accumulation of clashes. Maybe, in my innocence, I felt like I was trying to change the world by fighting against it. Writing the play was part of my process of understanding that in addition to being my father, he was often the spokesperson for the speeches that preceded him and that continue to be broadcast.

I was not the first and I will not be the last person to have hurt with their father or with the male world. My intention with the piece is therefore not to expose the arguments I had with my father, but rather to create a sensitive space for dialogue on points on which we might disagree, particularly on the topic of masculinity. And if this conversation is not possible with him in real life, let it be possible with the public.

For me, it is precisely about making this “impossible conversation” possible through the encounter with the public, by focusing on transforming conversations that were once a promise of conflict and resentment into humor and dialogue. The conversation that “never happened” continues to occur and mature with each audience encounter.

How does the title “Joãozinha Desviada,” with its gender bending, engage with discussions of queer identity and dissent in the work? Does the “ant” represent an escape from rigid expectations of masculinity?

This name alone carries much of the discussion of the play. It mixes the masculine and the feminine, the augmentative and the diminutive… In the play, I say that “Joãozinha is the name of my ant”. The metaphor of the ant allows me to take a critical distance from the figure of man without having to occupy a gender position that is not mine.

When we talk about ants, we normally use the pronouns “she/her”, even though we don’t think of them as female, right? More than that, the ant ends up acquiring several meanings in the piece: it is a way of representing masculinities that deviate from the norm, or even other dissident identities, at the same time as it dialogues with the desire I myself had to “be smaller” when I was a child and struggling with my weight, and perhaps also with the desire to dissociate from myself in moments of emotional pain.

I understand the ant above all as the playful layer of this conversation, which allows my child to also be alive in the scene, curious and playful. And what discussions can be provoked when a man, looking like a man, pretends to be an ant? What if he started trying to blur that “man appearance”? All this to ask: “what is a man?” More than responding, I want to bring these tensions into play in the piece, from the title.

Does the toast to the audience with cachaça, as a “toast to nostalgia”, change the atmosphere and the actor-spectator relationship? Do you consider this gesture as a democratization of mourning, taking it out of private space?

Without fail. What matters most to me in this work is not to talk about the pain of losing my father, but rather to establish an experience of dialogue and exchange with those who are present, here and now. From the moment I greet the audience at the door, to the moment we close our eyes together and ponder a desire, to the moment I offer and serve the cachaça, and only then ask a more personal question to someone in the audience, all of this has a sequence designed to create a space of trust and intimacy.

Interaction with the audience is at the heart of this dramaturgy. Sharing the audience’s opinions, memories, and desires is crucial for the play to reach its beginning, middle, and end. Thus, in the creation of “Joãozinha Desviada”, the dramaturgy and staging are mainly motivated by the concern for audience involvement. How you introduce and carry out these shared actions, such as toasting, playing and reflecting on nostalgia, makes all the difference in the relationship between the audience and the work.

Thematically, grief and longing are also experiences that bring us closer together as human beings: everyone who lives long enough loses someone, everyone misses something (or at least the vast majority). And cachaça helps bring the audience into the same sensory atmosphere, especially after I revealed that there was cachaça at my father’s funeral. Besides, he would certainly like to be able to have a drink while watching this play.

Espaço Parlapatões – Franklin Roosevelt Square, 158 – Consolação, central region. Tuesday and Thursday, 8 p.m. Until 12/18. Duration: 60 minutes. From R$25 (half price) on sympla.com.br and at the theater box office