Pain that does not go away, sudden fever, unexpected discharge. Situations like these are usually enough to land many cancer patients in emergency rooms, as hospitals lack the support to answer patients’ questions remotely.

At Inca (National Cancer Institute), an initiative based on digital communication shows that many of these trips can be avoided when there is a direct channel between patients, family members and healthcare teams, allowing doubts to be clarified and behaviors to be adjusted without having to go to the hospital.

The proposal to develop an application fulfilling this function arose in 2017, inspired by studies that demonstrated a simple principle: when the patient can report their symptoms in real time and receive rapid guidance, there are fewer complications, fewer visits to the emergency room and a better quality of life.

Called Lila, the application is installed on the patient’s cell phone, and the patient can record symptoms, doubts or discomfort at any time, describing the intensity of the problem from their own perception.

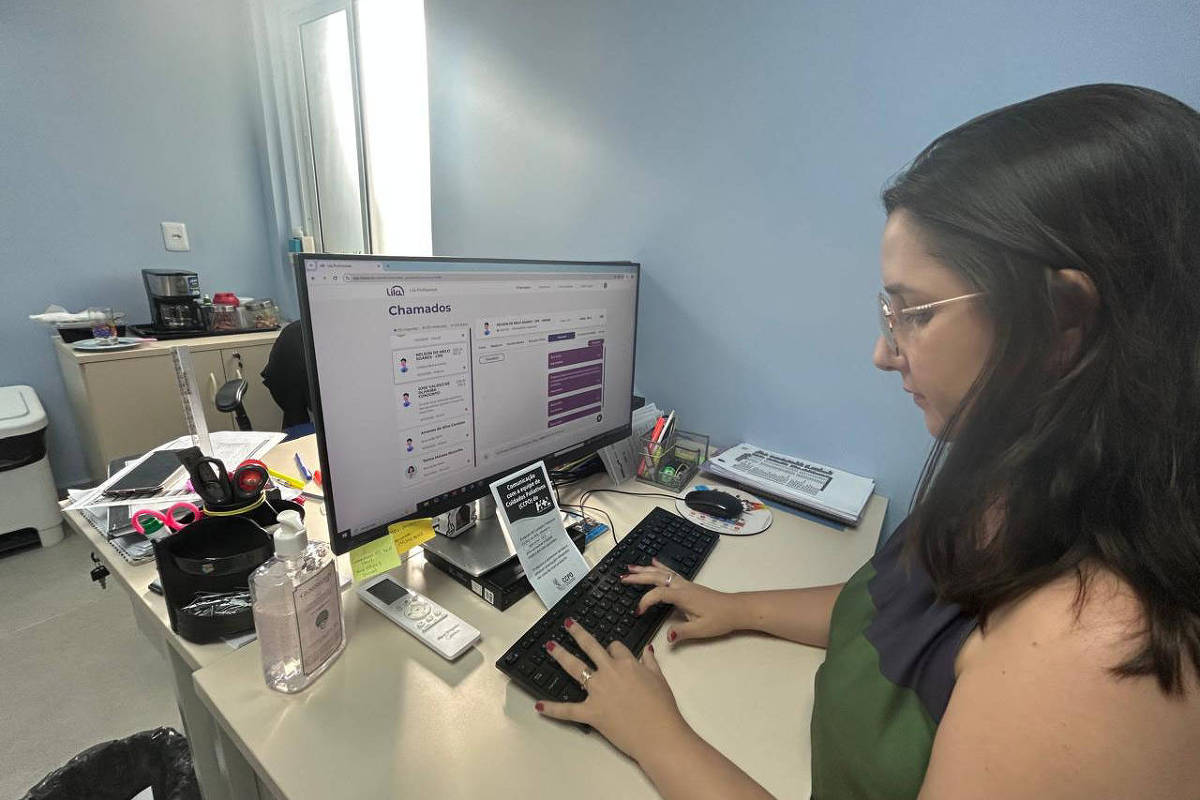

On the other hand, health professionals follow these messages on a platform that organizes requests and allows them to respond to them asynchronously, adjusting medications, directing conduct or clarifying doubts that, without this channel, would generate anxiety and the search for care in person.

According to Inca oncologist Carlos José Coelho de Andrade, one of the app’s developers, the logic reverses a traditional model in oncology. Between one appointment and another, which can take place every two or three weeks, the patient generally does not have direct access to the team.

“What happens in the meantime, if he doesn’t go to the hospital, cannot be resolved. When you create a communication channel, at least part of these requests can be met,” he explains, who reported on his experience at an international seminar on the fight against cancer, which took place in Rio de Janeiro.

This results in less prolonged suffering, particularly with regard to pain, identified in the literature as the main cause of visits to the emergency room among cancer patients.

According to Dr. Luiz Antonio Santini, who previously headed Inca, unnecessary visits to emergency departments can even harm the quality of treatment, because the patient will likely be seen by doctors who are unfamiliar with their care and who could potentially perform harmful interventions.

Lila began as a clinical study and gained traction in the field of palliative care, particularly home care. “When you use a tool calibrated for this purpose, care goes better,” says Andrade.

Although the data from the study carried out at Inca are still in the analysis phase, international literature indicates a constant reduction in emergency room visits with this type of tool. Research from Australia indicates declines of around 30%. Additionally, some studies show improved survival and reduced costs. “If it was a drug, it would have already been incorporated,” compares the oncologist.

Interest in the application spread organically and professionals from other regions of the country, such as Belém, Ceilândia (DF) and Janaúba (MG), began to adopt the tool, especially in contexts where getting to the hospital involves long distances.

In Pará, for example, the application has prevented the movement of cancer patients who live in remote areas and who can only reach the capital by plane or after many hours by boat, according to oncologist Daia Polianne Peres Hausseler, general coordinator of the Oncology Palliative Care Center at Ophir Loyola Hospital, in Belém.

Among the practical examples, the oncologist cites common situations in daily treatment. “A person on chemotherapy starts seeing spots on their skin, takes a photo and sends: ‘Doctor, since I took this medicine, I see this here. What should I do?'” he reports.

Sending images and messages allows for rapid and targeted assessment, without the patient having to leave their home. In more serious cases, the impact can be decisive.

Daia says one patient reported severe leg pain and difficulty walking. “He took a photo, we checked for a suspicion of thrombosis,” he says. After contact via the app, the team requested testing and began treatment in less than 48 hours. “Under normal circumstances, it would take more than two weeks,” he said.

Situations involving infections can also be identified at an early stage. “Patients who start to have a fever or a burning sensation when urinating, we can, through this contact, direct them and often start antibiotic therapy,” he explains.

According to her, without this monitoring, a simple infection can progress quickly. “The patient takes transport, goes to Belém, waits for the examination, and when the results come back, he has already entered sepsis,” he warns. Medication prescriptions are made digitally, according to the rules of the CFM (Federal Council of Medicine).

Daia points out that the app also helps define when in-person service is essential. “There are situations in which we perceive greater severity and recommend: ‘listen, in this situation I need you to move to Belém'”, he explains.

Currently, the service offers around 120 services per month, with over 500 patients already registered. The team includes 14 doctors. “Everyone has access to the platform, but we have a doctor who is on call from Monday to Friday directly on the application,” he explains.

In addition to technology, Lila touches on a sensitive point in cancer care: communication. Studies show that up to 80% of palliative care patients are unaware that they are in this phase of treatment, reflecting the difficulty in discussing sensitive topics.

According to Carlos Andrade, from Inca, by allowing the patient to direct the story by saying what they feel, when they feel and how it affects them, the tool reinforces more humanized and continuous listening, even outside the hospital environment.

The challenge is now structural. Although the cost of adoption is low compared to emergency expansion, it is necessary to reorganize the work of teams and ensure sustainability of funding.

The project was first made possible thanks to the resources of Fapesp (National Research Support Foundation of São Paulo), then thanks to collective financing and, more recently, thanks to a parliamentary amendment to Inca.

For Andrade, the natural path would be to integrate this type of strategy into public policies. “Funding qualified communication generates savings. It is a simple intervention, but with enormous potential impact,” he says.

The Public Health project benefits from the support of Umane, a civil association which aims to support initiatives aimed at promoting health.