“Down by the river, you can see tourists on bicycles. Here, there is not even that. This pink building is located in an area that is not very close to the center or to that part of the M-30 motorway that has been buried and renormalized. It is more artificial, but it also has similar effects on rental prices,” says researcher Javier Gil. It is one of the most unusual stops of the march in which members of the Urban Studies Group (GECU) and the Madrid Tenants Union participated last Thursday, November 6, through the Puerta del Ángel, as part of the International Conference. Maps of work on platforms in the digital city.

Pink house style Barbie It is completed with balcony lamps Indie In a sterile hall that reflects the space’s lack of soul. It’s the perfect example of the particular real estate process this Latinx neighborhood is experiencing: artificial, almost non-existent gentrification. The companies that cause this never finish starting; Its consequences, yes.

Alberto Crespo, a member of the tenants’ union who is writing a doctoral thesis on the housing situation in this area west of the capital, says about housing: “They started setting the price per night at 150 euros. Now it is 80 euros. And even then, it is usually empty and people who come do more than go out to see the city.” Aside from these hostels, a quick glance at the real estate portals shows a ground floor of less than 40 square meters at a price of 1,000 euros, which a few years ago no owner could charge more than 400 euros per month. To rent a larger house, with an area of less than 90 square meters on Caramuel Street, it is necessary to spend approximately 2,000 euros per month. Its price was previously around 800-900 euros in the worst case scenario.

Javier Gil comments that one of the companies taken over by the vulture Madeleine Fund (the big owner that made Puerta del Ángel a proving ground), the former Lottery Department, has been closed for two years. “They prefer it to opening another similar project that does not contribute to the transformation of the neighborhood. They are looking for things like a cafeteria and a restaurant that will serve them in the Tirso de Molina market, which is managed by a fund that also owns Sala Equis in central Madrid. This is the model they are trying to export to the entire neighborhood,” he explains.

This part of Puerta del Angel is the story of rents squeezed by smoke and nothingness. Other areas of the neighborhood or other environments can find, in the case of Legazpi, a direct relationship between improving infrastructure and communications and providing green areas that the burial of M-30 meant with rising housing prices. However, in Caramwell Street and many other surrounding streets, Madeleine was responsible for raising average rents by purchasing vertically owned buildings (with a single owner on all floors) which she then converted into ‘fashionable’ ground floor businesses and seasonal house rentals.

Number 14 is a fine example, with an enclosed wine cellar followed by several floors on the later floors where restored windows show the floors where replacement took place. As contracts were fulfilled, Madeleine imposed unsustainable increases or did not offer the possibility of renewal. “The ones who didn’t renovate were the tenants who held out, in this case because of the old rent. The ones who held out were characterized by the windows,” Alberto insists.

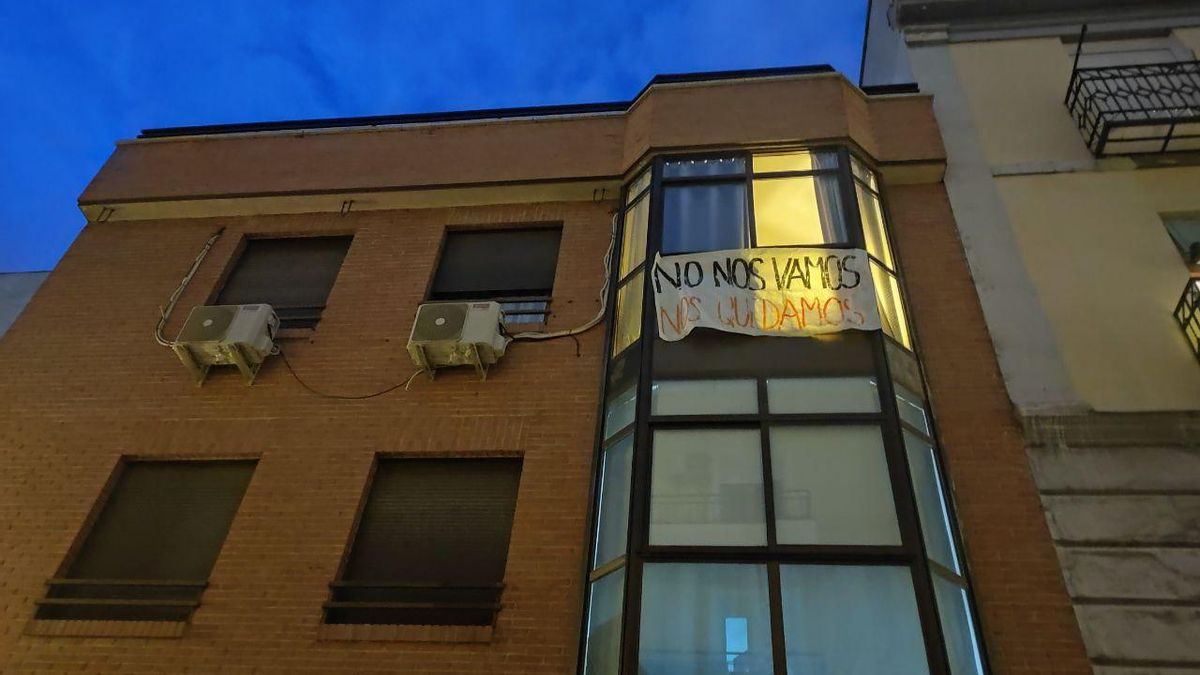

On other occasions, those who stay do so with greater difficulty. On Juan Tornero Street, a few meters from a shop that served as the center of Madeleine’s operations before neighborhood pressure forced them to move, only two windows have been renovated, both on the top floor. “A neighbor took up this strategy We stayThis is supported by the Tenants Union. Proof that you are continuing to pay the amount you paid before the increase or threat of eviction, as well as that there is no alternative to housing. This usually leads to a court process lasting about three years, where you deposit the money in court because the landlord won’t accept it. “This lack of income on the part of the landlord while the tenant continues to comply with his obligations reduces the power differential between the two,” says Alberto Crespo.

Currently in Puerta del Ángel there are two struggling blocs, with the entire population or the vast majority of the population organizing against the eviction that is imminent or already underway. One of them is located on Antonio Zamora Street, where a sign in its windows carries the message “We are not leaving, we are staying.” It’s about the windows. The building is facing an eviction attempt by the investment fund Dolamer SL Mercedes Hoces Moreno, one of the richest women in Spain and the largest shareholder of Grupo Planeta, is involved in this entity that intends to evict ten families without even offering them the possibility of paying more. “He wants to create tourist accommodation,” says Javier Gil.

In front of another of Madeleine’s colorful buildings, the academic explains the process that led to the current disastrous housing situation. The legislative changes promoted by the governments of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and Mariano Rajoy during the presidency of Pedro Sánchez have hardly been corrected (and even less so in this last legislature, where “junts prevent increased controls on the fraudulent use of seasonal rents applied to permanent tenants”). Madrid’s transformations have been intensified by regional and municipal governments, such as the sale of 1,800 public housing units to the vulture fund Blackstone during Ana Botella’s mayoralty.

The adjustments that, in the face of the mortgage and banking crises, facilitated a “speculative dynamic” that was not necessarily caused by a lack of supply or a rise in demand. Javier Gil emphasizes: “We see that the practices reach even areas where the population is declining. Housing is a system of expectations, divorced from the real value of the object.”

It’s a matter of expectations. The story of a modern ecosystem that suits, or appears to be, “digital nomads”: professionals in sectors such as technology and finance, temporary workers or students of expensive postgraduate courses who can pay up to 1,500 euros per month for a room with bathroom and kitchenette. The funds that operate the Puerta del Ángel play a role in this. For this reason, the wealthier classes, which have not finished settling, coexist with the popular classes or workers from the more precarious sectors. Just as this neighborhood, led mainly by Extremadurian and Andalusian immigrants, abandoned its status as a suburb without fully embracing a centre, its residents now live a kind of strange balance between the consequences of speculation and the resistance to their privacy.

In the Tirso de Molina market, in the middle of the pedestrian process, the cafeteria and restaurant are doing well. However, a few meters away, a similarly themed pizzeria continued to operate for a few months. Old pubs and dry cleaners with cane signs speak of a time that refuses to become history. Things of constant tug of war. It also shows up in the frames of eroded facades and the windows of apartments abandoned by a property that refuses to renovate them if the tenants do not give up first. People who just want to open doors and windows to ventilate their homes or greet their neighbors.