The mug with I ❤️ NY is still in my closet. I’m not the only one. He is also among so many of us who find in his nostalgic promise a call to give our all to reach our peak, mentally humming with Frank Sinatra.

This cup is an artifact of emotional archeology. A remnant of when New York was not simply a city, but an aspiration.

Getting there meant something. When the city’s threshold generated an epiphany, just like castles or cathedrals: an internal change simply by passing its magnificent thresholds.

Since Ayn Rand wrote The spring 80 years ago – that epic story of the making of New York that became a survival manual for the ambitious, talented and individualistic – many went to New York to test themselves in the most difficult terrain. New York has been the destination for the elite for decades and for all those who wanted to reach the top or die trying.

New York, more than a city, has been a mental territory. A global brand with two aspects: the everyday, that of physical perception, and the symbolic, highly emotional.

The physical threshold was marked by the promise of exuberant luxury or the aspiration to reach the skies. On an emotional level, the threshold came from knowing that he was the author of a triumph recognizable to all, achieved through unbridled ambition and effort.

For some years, Hyperdigitization has reduced the need for a physical territory to represent success. With Covid the screws changed. To influence it was no longer necessary to live in New York, step on those sidewalks or breathe that polluted air. With a laptop and an internet connection, you can conquer the world from Florida, Texas, Bali or Valencia, where the climate and cost of living are better.

To fully feel, New York was no longer a guarantee of anything.

The data proves this. The city lost nearly half a million residents between 2020 and 2024. And to this day, about 40% of millennials say they are considering leaving New York, and 20% of Manhattan’s 463 million square feet of office space is empty.. The city that never sleeps seems to be taking a nap.

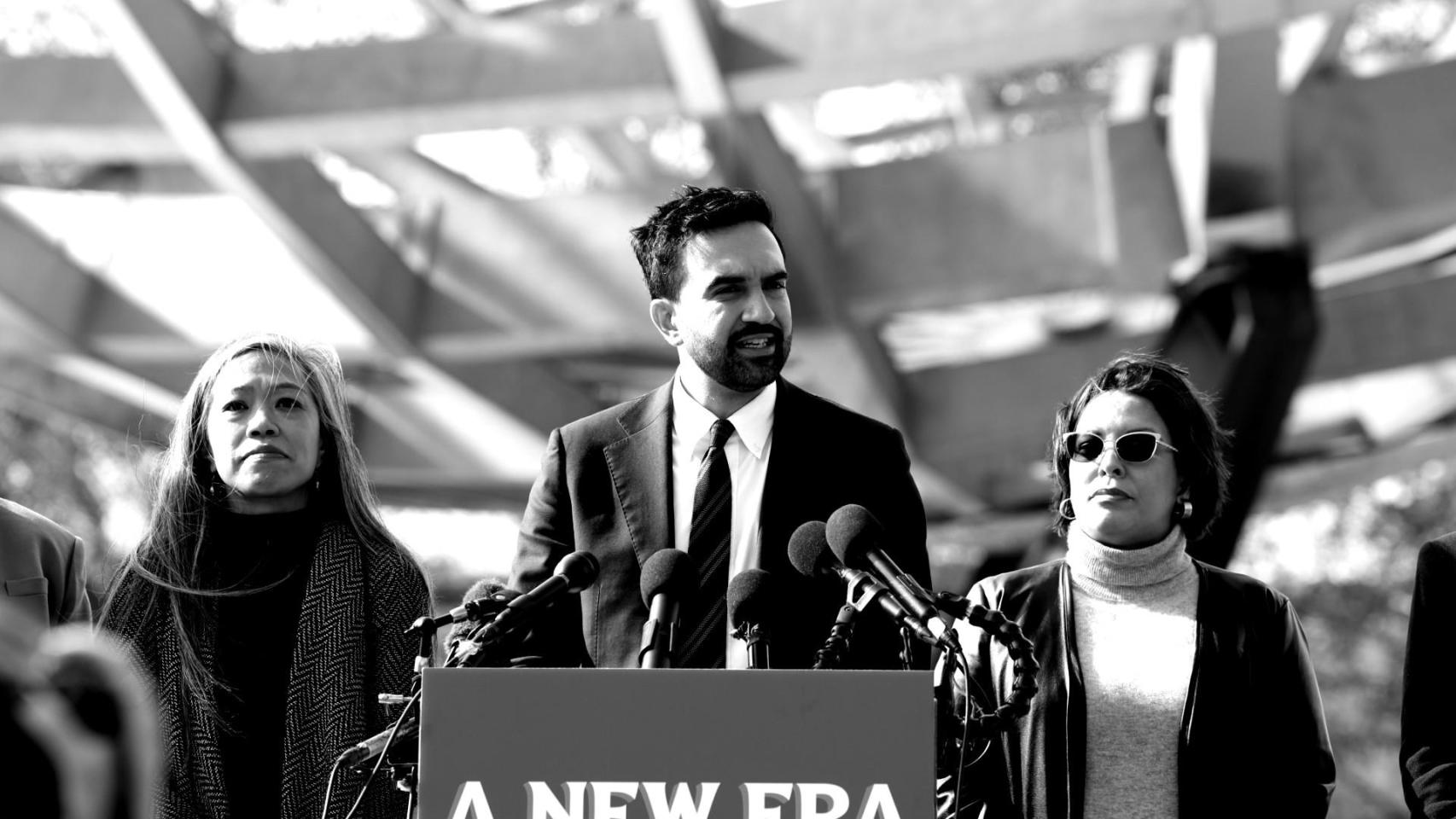

And yet, just when the terminal diagnosis seemed confirmed, New York chose Zohran Mamdani34 years, as its first Muslim mayor, in municipal elections with the highest participation since 1969. More than two million people voted. The city has changed.

But It is advisable not to confuse movement with resurrection.

Mamdani arrived with 100,000 volunteers, absolute control of the networks and a message as simple as it was seductive: accessibility.

He defeated Andrew Cuomo, who was trying to return after resigning in 2021 over allegations of sexual harassment, and Curtis Silwa, a Republican no one took seriously. He won because the alternative was a leftovers menu.

And, if that wasn’t enough, Eric Adams, the outgoing mayor, also does it, dragging scandals and the worst approval numbers in history. A competitive context that bordered on pathetic, in which Mamdani received 50.4% of the vote. In other words, a clear victory, but not overwhelming.

And who voted for him? Young people: they were the ones who drove historic early voting records. Those who never had an apartment in Manhattan and don’t care voted for him. For them, New York is not epic. It’s very expensive. And Mamdani promised them access.

But there is a nuance: Jewish voters favored Cuomo over Mamdani by 29 points, 60% to 31%. And the Jewish community in New York is not simply large – it is the largest outside of Israel – but it historically determines what has defined this city: money.

For generations, German Jewish immigrants established the financial houses that defined Wall Street: Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, Kuhn Loeb, Salomon Brothers. These companies transformed the United States from a debtor nation into a financial superpower.

And they continue to exert a profound influence on New York, as a community that, although it no longer monopolizes Wall Street, continues to hold sway in investment, philanthropy, real estate development and culture. In fact, in New York, more than in any other American city, money is not just economics: it is identity.

So apparently Mamdani won with youthful enthusiasm but without institutional consensus.

And although Mamdani is an avowed socialist, as a representative of greater New York, he opened his victory speech by quoting Eugene Debb and promising “the most ambitious agenda” for almost a century. Words that critics question, pointing out his relative executive inexperience and the challenges in fulfilling his highly progressive agenda.

Because promising accessibility in New York seems naive at best.

The New York dream has always been elitist, Darwinian, brutal. It was conquer or die. It wasn’t “everyone fits”. The allure of New York has never been inclusive. It was the seduction of vertigo, of those who dare, of those who don’t ask for permission.

And here’s the problem: making New York accessible doesn’t guarantee its revitalization.

It can simply make it a reasonable, fair and inclusive city. And boring. Because this city that seduces because it is unattainable may stop seducing when it becomes accessible.

In your best moments, New York was more than a city.

It was the mirror in which the world looked at itself with a desire for greatness. From Madrid, from São Paulo, from Tokyo; New York represented the promise that if we were hungry enough, if we were willing to sacrifice everything, we could reach the top.

It didn’t matter where you came from. It mattered how far you were willing to go.

That promise has been diluted. First with digitalization, then with Covid, finally with boredom.

And when New York ceased to be important, something emerged in the global imagination. We have lost the place where we can measure ourselves, where we can fail resoundingly or triumph gloriously.

We have lost the mirror where we can look at ourselves with a desire for greatness. And in their place we have the pixels, the likes and the lukewarmness of those who no longer aspire to achieve anything because their frustration is immediately appeased when they open their cell phone, and based on clicks, instead of fighting for real change.

In this new reality, New York is not dead. It simply stopped mattering.

With Mamdani, the city has one last chance. Maybe it will work, or maybe we will discover with it that, by distributing ambition as a right, we make it trivial. That the price of making it accessible is emptying it of its epicness.

Time will tell. For now, what we have is not a Resurrection. It’s an experiment.

My I ❤️ NY mug is still in the closet. But I no longer know whether to look at it with nostalgia or with a sense of humor. There it stays. I still like it.