It’s been difficult to draw any reassurance about the future ahead of us – the future has arrived well before 2025, and that’s not a good thing. He came at a gallop, with no desire to overthrow the previous cosmology. For veteran analyst Alastair Crooke, a former agent of the British intelligence service MI6 and founder of the Beirut-based Conflict Forum, Western conservative populist thinking has already managed to take root as something more crude, coercive and radical.

- Budget 2026: Congress approves 61 billion reais for parliamentary amendments and minimum wage of 1,621 reais

— Kaputt the model of a rules-based international order (if it ever existed beyond the narrative) — writes Crooke in the essay “A New Age of Coercive Rule.”

- End of 6×1 scale: Topic will ‘definitely’ be on House agenda in 2026, says Motta

The war for future power is already being fought – with no rules, no rights, few limits and blatant disregard for the United Nations Charter. According to Crooke, the tactic adopted by the aspiring masters of the future is to leave their opponents stunned and immobilized, frozen in time and action. These are moments of deliberate transgression with the aim of shocking, acting quickly and, in doing so, destroying the previous (dis)order. The United States of Donald Trump and the Israel of Benjamin Netanyahu believe that they are at the forefront of the fall of global liberalism and its illusions.

Political essayist Giuliano da Empoli, author of the marvelous novel “The Magician of the Kremlin”, inspired by the real story of Putin’s eminence grise, Vladislav Surkov, deepens his vision of our future. In a new book entitled “The hour of the predator: meetings with the autocrats” (not yet published in Brazil), an entire political class of technocrats (right and left), more or less indistinguishable from each other, who governed their countries on the basis of the principles of liberal democracy, in accordance with the rules of the market and modulated by certain social considerations, emerges from the scene, forming the Davos Consensus. Under the razor-sharp pen of Da Empoli, the annual concoction held in Switzerland goes down in history as a place where politics was reduced to a competition between PowerPoint presentations, and where the most transgressive move one could make was to wear a black turtleneck instead of a light blue shirt to drink.

The new global tech elites – the Musks, the Zuckerbergs and Sam Altmans – have nothing in common with the technocrats of Davos. The life philosophy of these AI barons is not based on managing the existing order, but on the contrary on an irrepressible desire to shake up everything. Order, prudence and following the rules are anathema to those who quickly gained fame and fortune, by breaking things, as Facebook’s original motto said.

At the incendiary London rally that shocked the British establishment a few months ago, Elon Musk announced the “coming arrival of violence” and called on everyone:

— Either you react or you die.

His overt and unwavering support for far-right movements, from the Bolsonaristas in Brazil to the AfD in Germany, is not just due to the eccentricities of a South African-born billionaire. According to Da Empoli, this reveals something more fundamental, one that goes far beyond the preferences of a single tech oligarch. Musk’s words are, he believes, just the tip of something much deeper: a battle between power elites for control of the future.

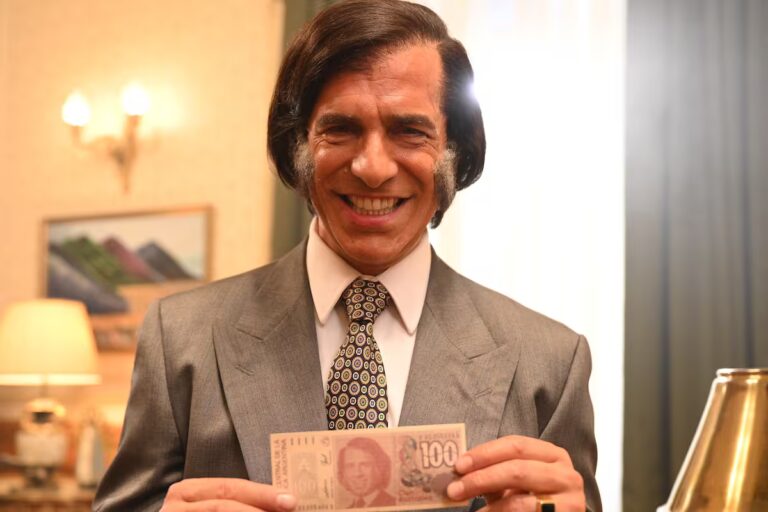

In their nature and trajectory, today’s high-tech overlords have more in common with far-right national-populist leaders—the Trumps, Mileis, Bolsonaros, and leaders of similar European movements—than with the politicians who have governed Western liberal democracies for decades. Like the former, they are almost always eccentric characters who have had to break the rules to thrive. And like them, they are also wary of elites, of specialized knowledge, of everything that embodies the Old World. They are also convinced that they can shape reality according to their conceptions, that virality (and of course also virility) prevails over the truth, speed is put at the service of the strongest. A complete disregard for civil servants and the democratic rule of law is another common denominator.

Such an approach proves attractive for a public opinion inclined to consider the institutional system blind, deaf and mute to popular afflictions and convinced that voting for this or that politician does not change much in life as it is. Da Empoli fears that liberal democracies, large and small, are in danger of being swept away, like the small Italian republics of the early 16th century.

— If, in theology, a miracle corresponds to the direct intervention of God, who circumvents the normal rules of earthly existence to produce an extraordinary event, the logic of Trump and other national-populist leaders is similar — he writes. — Breaking the rules (and often the laws themselves) to intervene on the problems that afflict their voters: this is the promise of a political miracle.

Shoo, you better not believe in miracles.