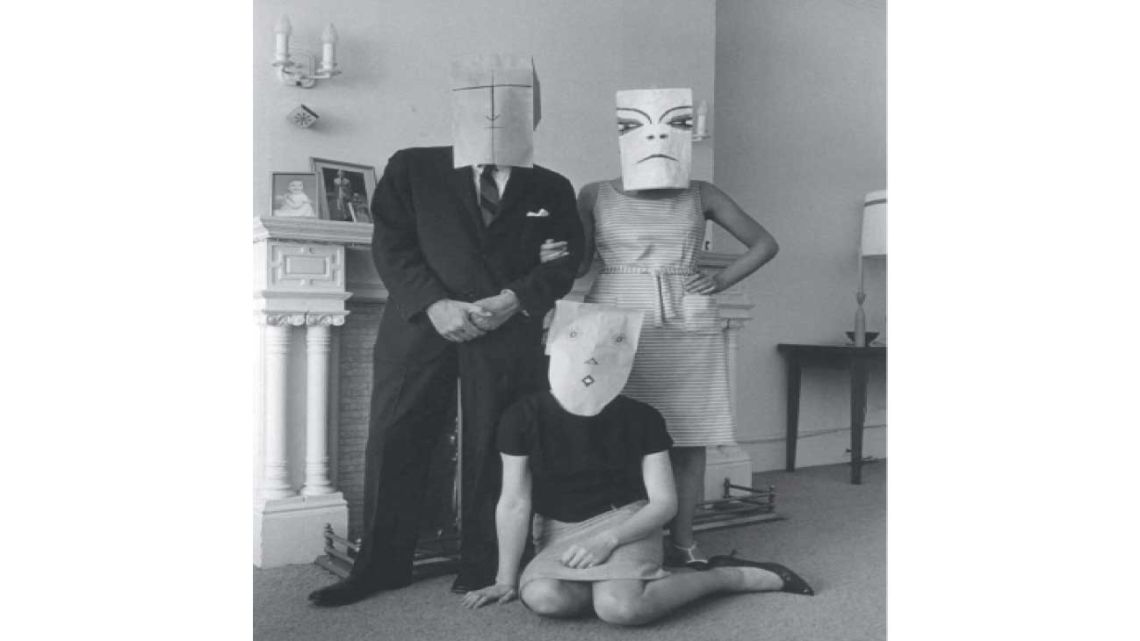

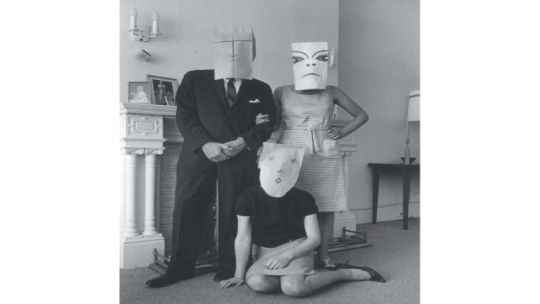

“Give him a mask and the man will tell you the truth,” said Oscar Wilde, who knew a lot about the human species. Another who shared the incurable relationship between the obscured face and becoming other with a certain drive for the authentic and truthful was Saul Steinberg, the great illustrator known for his 60 years as a contributor to The New Yorker. In the project he carried out by drawing faces on brown paper bags to obscure the faces, his own and those of his friends, the idea of the costume is evident, but also the will to think that he expressed through lines and strokes.

The Romanian Steinberg, born in 1914, experienced the turmoil at the turn of the century first hand. In 1933 he went to Italy to study philosophy. He graduated in 1940 and was forced to leave the country the following year due to fascism’s anti-Semitic law. He arrived in Santo Domingo to await a visa to enter the United States, where he died in 1999. He saw drawing in all its forms as a form of thinking on paper. With irony and without irony, with an expressive affectivity in his human characters, Steinberg’s work is not just that of a cartoonist, since they were largely men facing a slightly confused world.

To the limits of reflection, as if signs, numbers and letters were not enough to understand reality. As if the space on the paper wasn’t enough, he turned his attention to the objects. Cats with bodies like benches and the famous painted woman in a bathtub. The world was imperfect. Steinberg knew it. He just tried to correct it a little.

Authoritarians don’t like that

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a mainstay of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe that they are the owners of the truth.